The Great Arab Conquests (38 page)

Read The Great Arab Conquests Online

Authors: Hugh Kennedy

TOP Cordova (Spain). The old Roman city was taken without much difficulty and soon became the capital of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). The great mosque was begun sixty years after the first Muslim invasions. (Author)

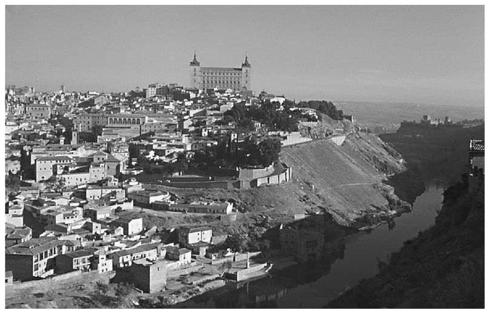

ABOVE Toledo (Spain). Despite its superb natural fortifications within the bend of the Tagus river, the Visigothic capital of Toledo seems to have put up little resistance of the Muslim armies. (Author)

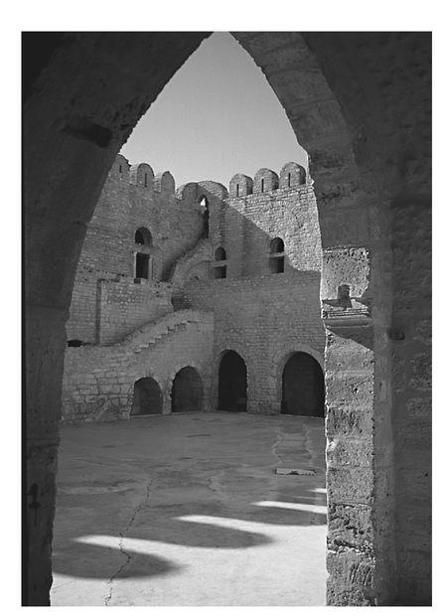

LEFT The Ribat of Sousse (Tunisia). This ninth-century fortress guarded the harbour at Sousse on the coast of Tunisia from which Muslim raiders set out for the coasts of Sicily, Italy and the south of France. (Author)

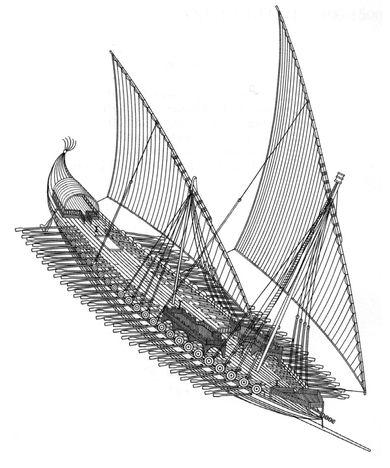

TOP RIGHT Modern reconstruction of a Byzantine dromon. With its oars and its twin lateen sails, the dromon was the classic warship of the Byzantine navy at the time of the Arab conquests and it is likely that Muslim naval ships were very similar in design. (Drawing reproduced by the kind permission of John Pryor, from his book The Age of the Dromon, Leiden, 2006, frontispiece.)

ABOVE Tyre (Lebanon). The old port of Tyre was the main Muslim naval base on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean from c. 730 to 861. (Author)

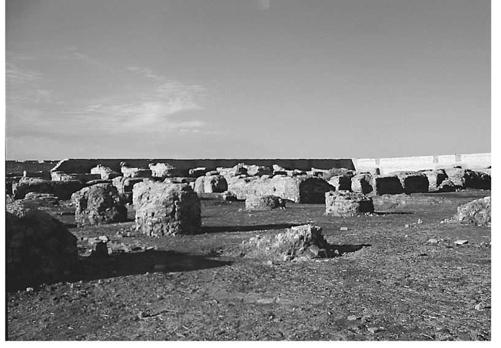

TOP The site of early Muslim Basra (Iraq). Little remains of the site old of Basra, founded by the Muslims immediately after their conquest of southern Iraq and no scientific excavations have ever been undertaken. (Author)

ABOVE The centre of old Kūfa (Iraq). In the foreground lie the ruins of the governor’s palace, the first phases of which may date back to the time of Sa‘d b. Abī Waqqās. In the background lies the much-rebuilt mosque. (Author)

THE CONQUESTS REMEMBERED

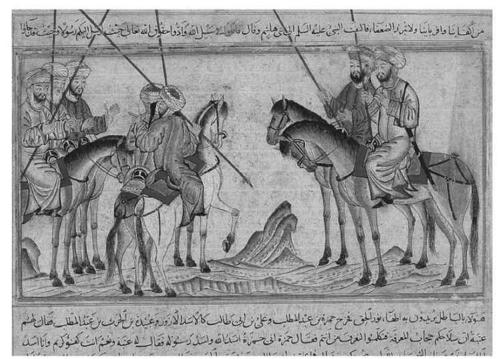

ABOVE The Prophet Muhammad (centre, on the white horse) preparing for his first battle against the Quraysh of Mecca at Badr in 634. This early fourteenth-century Persian view of the first Muslim armies, shows them without any body armour and only the simplest military equipment. (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art)

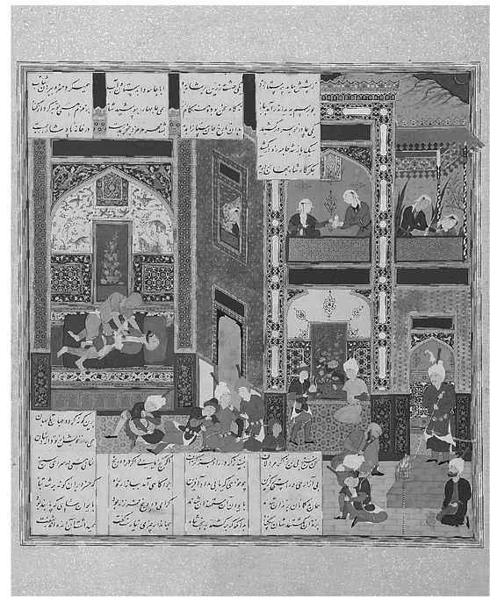

LEFT A fifteenth-century Persian manuscript shows the murder of Chosroes II by his courtiers in 628, an event which caused political chaos in the Sasanian Empire and allowed to Muslims to take advantage of the confusion. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr, 1970.301.75)

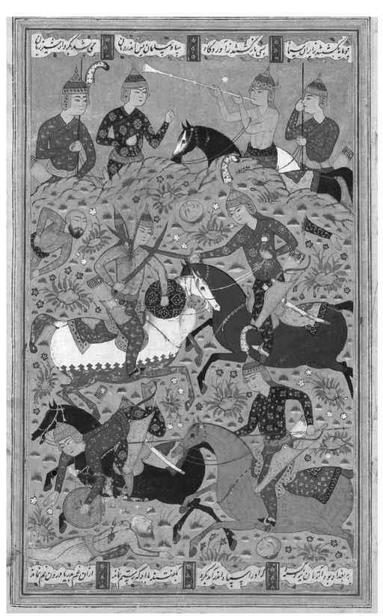

LEFT The battle of Qādisiya as seen in a fifteenth-century Persian book painting. This personal encounter between the Arab commander Sa‘d b. Abī Waqqās and the Persian general Rustam never took place but the Muslim victory at Qādisiya opened the way for the conquest of Iraq. (British Library)

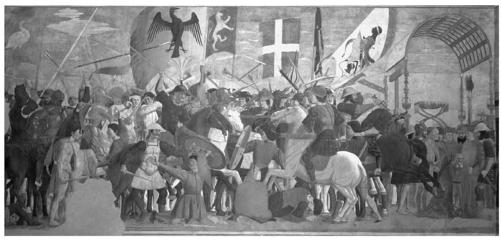

BELOW Piero della Francesca, Legend of the True Cross in the church of S. Franceso in Arezzo (c. 1466). This panel depicts Heraclius’ defeat of Chosroes II in 627 which led to the return of the True Cross to Jerusalem in the same year in which Muhammad came to an agreement with the Quraysh of Mecca, the prelude to the Muslim conquests. (San Francesco, Arezzo, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library)

The survival of the Persian language was accompanied by the survival of aspects of Persian political culture. In the princely courts of northern and north-eastern Iran where the first wave of Arabs hardly penetrated, rulers still looked to old Iranian models and claimed descent from the Sasanian kings and noble families. These courts functioned almost like reservoirs of Iranian culture, and it was from them that the Persian renaissance, the great cultural revival of the tenth century, emerged with works such as Firdawsi’s

Shahnāmah

, the Book of Kings.

Shahnāmah

, the Book of Kings.

This survival of the non-Arab culture of Iran was in part the result of the nature of the initial Arab conquest, the very slow pace of Arab settlement and the way in which the conquerors were happy to leave existing power structures intact. The country became firmly Muslim. Among the myriad princes and nobles there was never to be another non-Muslim but, at the same time, the Persian language and identity lived on into the twenty-first century.

Other books

Seer: Reckless Desires (Norseton Wolves Book 8) by Holley Trent

The City Baker's Guide to Country Living by Louise Miller

Turning Grace by J.Q. Davis

Historia de dos ciudades (ilustrado) by Charles Dickens

If Only In His Dreams by Schertz, Melanie

Business Doctors - Management Consulting Gone Wild by Sameer Kamat

The Case of the Double Bumblebee Sting by John R. Erickson

Body Hunter by Patricia Springer

Mr. Monk is a Mess by Goldberg, Lee