The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities (51 page)

Authors: Matthew White

As befitted an earthly paradise "all young boys must go to church every day, where the sergeant is to teach them to read the Old Testament and the New Testament, as well as the book of proclamations of the true ordained Sovereign. Every Sabbath the corporals must lead the men and women to the church, where the males and females are to sit in separate rows. There they will listen to sermons, sing praises, and offer sacrifices to our Heavenly Father, the Supreme Lord and Great God."

8

The new movement abolished foot-binding, in which the feet of girls were crushed into the small, delicate, and impractical shape that was considered beautiful among the Chinese. They also abolished the hair braid that all Chinese men were required to wear as a sign of servitude to their Manchu masters. This gave the Taiping armies a savage appearance as both men and women charged into battle with defiantly big feet and long, wild hair.

For all of the utopian ideals of Taiping society, hypocrisy abounded. For most members of the movement, men and women were kept strictly separated, but the leaders gathered harems fit for Old Testament kings, not to mention attendants, servants, and pomp appropriate to their positions.

The People You Meet in Heaven

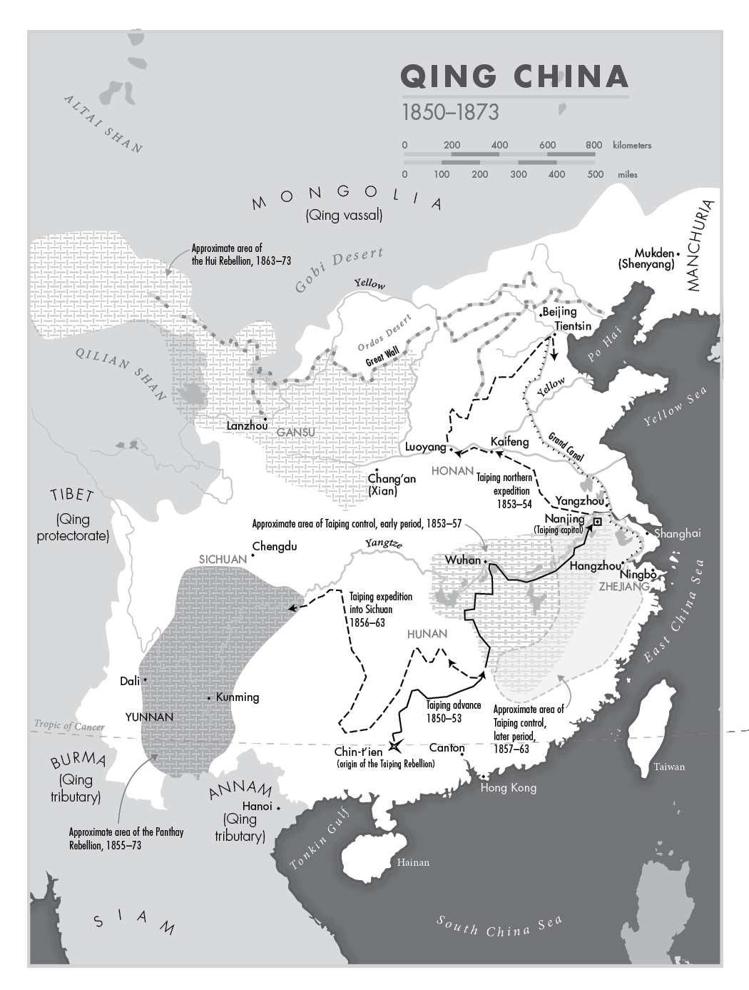

By 1853, Hong had started to withdraw from the secular business of his Heavenly Kingdom and devote himself to spiritual growth. Although both the West King and South King had been killed in the battles that brought the Great-Peace Heavenly-Kingdom into power, there were still three lesser kings to handle the minutiae of running the empire.

One of them, Yang Xiuqing, the East King, had begun as an orphaned charcoal maker, but he had an instinct for military tactics that secured many of the Taiping successes. Yang now started to have his own visions from God, and if you know anything about messiahs, you can guess the nature of these visions. Apparently, God was totally disenchanted with Hong, and now wanted to promote Yang to messiahood in his place.

In September 1856, rumors of Yang's ambition reached Wei Changhui, the North King, so he marched his army back from the front and attacked Yang's palace, slaughtering Yang and his family. Wei's troops triumphantly paraded Yang's head on a pole through the streets of Nanjing, until Hong emerged from seclusion to denounce this atrocity. Hong seized Wei and sentenced him to be publicly flogged to death. He invited the survivors of Yang's clan to watch. After the witnesses arrived, however, a trap was sprung. It turned out that Hong and Wei were in collusion, and now that the remaining Yangs had come out of hiding and gathered in one place, Wei and Hong finished wiping them out.

Shi Dakai, the Wing King, was out campaigning in the field at the time. He had originally come from a wealthy family and had convinced many rich kinsmen to contribute money and property to the nascent Taiping movement. Upon returning to Nanjing, Shi expressed some doubt to Wei about the propriety of wiping out the Yangs. Wei took this criticism as a challenge, and Shi barely escaped the city alive. Even so, Wei caught and killed Shi's wife and mother. After taking refuge with his army, Shi marched back toward Nanjing with 100,000 troops, hungry for revenge. Hong quickly bought him off by making him a gift of Wei's severed head.

Shi Dakai was now the last of the lesser kings, and probably the least crazy. Satisfied with Wei's head, he returned for a short while to Hong's entourage, but he eventually broke from the Taiping movement altogether. He took his army into the Sichuan basin and established his own independent enclave.

Western Response

The Qing government, meanwhile, ruthlessly worked to contain the revolt. Officials kept it out of Canton by having over 32,000 suspected Taiping sympathizers beheaded by May 1856. An eyewitness reported that "thousands were put to the sword, hundreds cast into the river, tied together in batches of a dozen. I have seen their putrid corpses floating in masses down the stream—women too among the number. Many were cut to pieces alive. I have seen the horrid sight, and the limbless, headless corpses, merely a mass of flayed flesh . . . that lay in scores covering the whole execution ground."

9

The Taipings hoped to reach an agreement with the countries of the West. Not only did they share a nominal Christianity with the Europeans, but since 1856, the Anglo-French had been fighting a Second Opium War against Qing China. By the time that war ended in 1860, the Europeans had taken and destroyed the emperor's Summer Palace outside Beijing.

The West considered its options. Maybe it was time to take complete control of China and replace the corrupt and xenophobic Qing dynasty with Westernized puppets. For several years, the West had considered the Taipings to be proper Christians worthy of moral support at least. When Hong's strange heresies became more apparent, the West returned to supporting the devil they knew, the imperial Qing. They accepted a peace treaty that left China unchanged.

It wasn't just the Western statesmen and clergy who changed their minds about the rebels. In London, Karl Marx grew disillusioned as well. In 1853 he had hoped that "the Chinese revolution will throw the spark into the overloaded mine of the present industrial system and cause the explosion of the long-prepared general crisis." (Marx with a metaphor was like a dog gnawing a bone—determined to get everything he could from it.) By 1862, however, he considered the Taipings "an even greater abomination for the masses of the people than for the old rulers [only capable of] destruction in grotesquely detestable forms, destruction without any nucleus of new construction."

10

Hoping to connect with their presumed sympathizers in the West, a Taiping column set out in 1860 for Shanghai, which had become an international protectorate under Western control in 1854. Unaware of the shifting winds in Western attitude, the Taipings were startled to find European security forces firing at them in the outer defenses of the city. Because they assumed it was a mistake, 300 Taipings were killed without even returning fire.

Soon, the Europeans were aiding the Qing government more openly. The port city of Ningbo had fallen to the Taipings in 1861 with no opposition, and the residents had easily acclimated to their new rulers. In 1862, an Anglo-French expedition retook the city and turned it over to the Qing forces, who retaliated against the city with the torture and killing of random inhabitants as an example to the rest.

11

Independent contractors also helped the Chinese government by training and equipping government armies with the latest weaponry. The Ever-Victorious Army, a band of mercenaries raised mostly on the docks of Spanish-controlled Manila, fought under an American commander, Frederick Ward, against the rebels.

12

When Ward was killed in battle, command went to a veteran British officer, Charles Gordon, who would gain even greater fame many years later when he was besieged in Khartoum by the screaming dervishes of the Sudan (see "Mahdi Revolt").

More important than foreign mercenaries, however, were the native Chinese armies that were being trained and equipped like Western armies. The Qing deployed modern gunboats on their rivers to bring heavy artillery to bear on the walled cities of the Taipings. Manchu generals chipped away at the Taiping kingdom during the 1860s with new, modernized armies, but the reconquest was slowed by the Qing policy of taking no prisoners. This forced even the most disillusioned Taipings to fight to the last.

Qing forces overran the Sichuan enclave of Shi Dakai, the former Wing King, in July 1863. Shi was captured and publicly killed by slicing, while his followers were massacred despite a promise that this wouldn't happen. Finally, the Qing brought Nanjing itself under siege.

Hong Xiuquan became sick and died in May 1864, but no one knows how this happened. Poison is the most likely culprit, most historians lean toward suicide, but assassination has its proponents as well. Another possibility is that he was accidentally poisoned by some lethal combination of elixirs and potions he was taking to strengthen his mojo. In any case, his untimely death occurred only a couple of months ahead of his followers'.

Nanjing fell to the government in July 1864, followed by a general massacre of its inhabitants. According to the Qing general on the scene, "Not one of the 100,000 rebels in Nanjing surrendered themselves, but in many cases gathered together and burned themselves and passed away without repentance."

13

Hong's fourteen-year-old son, who had been proclaimed the new King of Heaven, fled after the fall of Nanjing, but his younger brothers were among the thousands killed when the city fell. The young Hong tried to disappear into the countryside, but he was caught, imprisoned, and executed by slicing.

Legacy

The game of mah-jongg was probably invented by bored Taiping soldiers. Beyond that, the Taiping Rebellion has faded into forgotten history. When Hollywood began to explore the possibility of a movie based on Caleb Carr's

Devil Soldier

, the story of the American mercenary Frederick Ward in the Taiping Rebellion, one of the first things to change was the setting.

14

The interested parties eventually filmed the basic concept as

The Last Samurai

, the story of a nineteenth-century American mercenary caught up in a civil war in, well, Japan obviously.

The Taiping Rebellion is the perfect example of the old adage that the winners write the history books. Most writers treat the Taipings as poor deluded peasants following a madman's hallucinations, but when you get right down to it, that's how most religions begin (not

your

religion obviously, but all the other ones). The only difference between Hong and history's successful prophets is that if a professor, novelist, or cartoonist disrespects Hong Xiuquan, angry mobs won't call for his head.

Is fear of its followers really the best test of a religion's authenticity? I'll admit that's the standard I use, but it's probably a good idea to remember that if the Taipings had won their rebellion, they might today be considered totally legit and every bit as Christian as the Mormons ("mostly, sort of").

CRIMEAN WAR

Death toll:

300,000

1

Rank:

96

Type:

international war

Broad dividing line:

everyone vs. Russia

Time frame:

1854–56

Location:

Black Sea

Major state participants:

Russia vs. Turkey, France, Britain

Who usually gets the most blame:

everyone except the Turks

Another damn:

war of trenches and idiotic frontal assaults

T

HE ONE THING EVERYONE SHOULD KNOW ABOUT THE CRIMEAN WAR IS THE

mind-boggling incompetence displayed by everyone involved. This war gave us “The Charge of the Light Brigade”—possibly the best-known poem in the English language—which describes the dumb courage of a futile frontal assault. The Crimean War was the first war to be photographed and reported on by war correspondents for the daily newspapers. It was also the first war to shock and horrify the people back home. The only individual whom history remembers kindly was a civilian woman, Florence Nightingale, who took it upon herself to nurse sick and wounded soldiers after the army proved incapable of the task.

The war began stupidly as well. Orthodox and Catholic clergy in Jerusalem were bickering over which of them had priority at the holy shrines. The Orthodox clergy appealed to Tsar Nicholas I of Russia to plead their case with the Ottoman sultan, the ruler of Palestine. The Russians overreacted and insisted that they be recognized as the protectors and spokesmen for all of the Christian minorities under Turkish rule. This would, in effect, make Turkey a Russian protectorate, unable to take any action without Russian permission. To make matters worse, as their negotiator, the Russians sent a man who absolutely detested the Turks ever since a Turkish cannonball castrated him in an earlier Russo-Turkish War.

When the Turks refused the tsar’s demands, the Russian army moved against Turkish vassals in the Balkans, the Romanian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, to force the issue. The Russian fleet from Sevastopol in Crimea caught and destroyed the Turkish fleet near Sinope on the Turkish coast.

Of course the rest of the world couldn’t let Russia conquer the Ottoman Empire unchallenged, so the British and French assembled an armada and expeditionary force, which they sent to back up the Turks.

The Turkish army, meanwhile, had moved up the Black Sea coast to meet the Russians head-on, and just south of the Danube, they fought the Russians to a standstill. Then Austria issued an ultimatum to Russia to quit now or be attacked by them as well. Grumbling and fuming, the Russians pulled back behind their border.

The war was over.

Except that the British and French allies had come all this way and didn’t want to go home without blowing up something. They had been languishing in camp along the Dardanelles strait, dying of typhus and cholera, waiting for their chance to attack, and they certainly weren’t going to let the war end without a fight. They decided to nip across the Black Sea and destroy the Russian naval base in Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula.

In September 1854, the allies landed north of the city and beat the small Russian field army at Alma. This left Sevastopol wide open for the taking, but the allies settled into siege lines and waited instead. At the Battles of Inkerman and Balaklava, the allies held off two Russian attempts to drive them away, and then winter set in.

No one had prepared to survive a Russian winter, and the allied army withered away from frostbite, chills, and hunger. By the time spring returned, the survivors were in no condition to press the siege toward a conclusion so the opposing armies just sat there, month after month, dying of dysentery and typhoid fever.

After almost a year, the allied armies had finally fixed enough of their problems to get the war moving again. In September 1855, a French assault took a critical fort in the Russian line, and the Russians abandoned Sevastopol, destroying the naval installations and scuttling the fleet on the way out. Treaty negotiations dragged on, but despite everyone’s best efforts, peace returned in March 1856.

2

Dynamo

The Crimean War was the first big war to be fought after the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Factories churned out mass quantities of identical guns, boots, bullets, tents, caps, and canteens. Railroads and steamships kept larger and larger armies resupplied at a greater distance. With the invention of the first mass-produced, easily loaded rifle ammunition (the Minie ball) in 1848, rifles quickly replaced smoothbore muskets on the battlefield, improving the range and accuracy of infantry fire. At Waterloo (see “Napoleonic Wars”) musketry had scored only 1 hit for every 459 shots fired, but in the Crimea, 1 bullet in 16 hit someone.

3

The Crimean War was probably the first great-power war that couldn’t be fought with tactics from the previous war, although that didn’t stop plenty of stubborn generals from trying to attack entrenched riflemen with Napoleonic charges. From here on out, every new war had to be figured out from scratch, usually after the first wave sent into battle had been torn apart.

With the massive increase in firepower, it became more difficult for attacking regiments to reach the enemy lines. There was a tendency for wars of this era to begin with maneuver and attack in the open countryside, but after all of the soldiers standing upright were swept off the field by improved firepower, the wars ended with deeply entrenched infantry waiting month after month in muddy sieges around key transportation hubs. Wars of movement slowed and stopped as armies hunkered down around cities like Sevastopol (1854), Petersburg (1864), and Paris (1871). This trend would eventually climax in the trench warfare of the First World War.

4