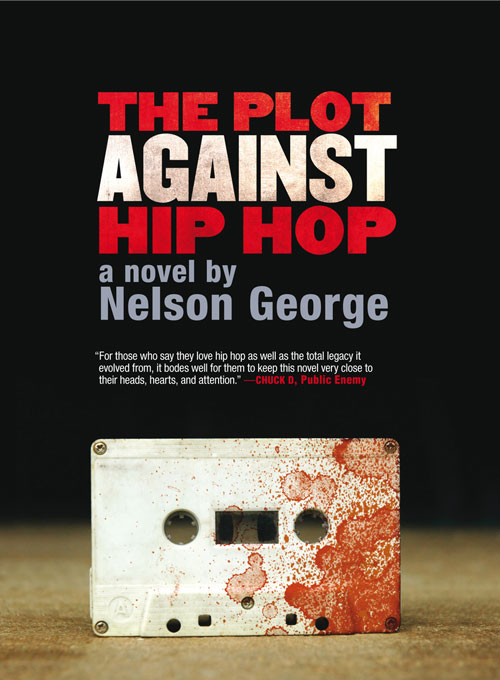

The Plot Against Hip Hop

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

©2011 Nelson George

ISBN-13: 978-1-61775-024-3

eISBN-13: 978-1-61775-082-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011923105

All rights reserved

First printing

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

[email protected]

www.akashicbooks.com

Table of Contents

Chapter 4: Never Seen a Man Cry Until I Seen a Man Die

Chapter 5: Lookin’ for the Perfect Beat

Chapter 6: Amerikkka’s Most Wanted

Chapter 9: Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos

Chapter 10: The Blueprint for Hip Hop

Chapter 11: Sound of the Police

Chapter 13: Party for the Right to Fight

Chapter 16: Round the Way Girl

Chapter 17: Da Art of Storytellin’ Part 1

Chapter 19: Talkin’ All That Jazz

Chapter 20: Things Done Changed

Chapter 21: As the Rhyme Goes On

Chapter 29: Time for Sum Aksion

Chapter 30: Empire State of Mind

F

lashbulbs exploded into white light and the rapid click of cameras felt like an automatic weapon aimed at an innocent iris. D Hunter blinked and blinked again, trying not to appear as dizzy as he felt. This was no way to keep a rich MC safe.

“Jay! Jay, look over here!”

The camera posse shouted and the rap star, record mogul, and living breathing brand, with the hottest chick in the game wearing his ring, paused for the paparazzi, looking dap in a creamy white suit with matching powder-blue pocket square, tie, and trendy shades. He gave them his trademark sly smile and gracefully manipulated an unlit cigar like a mike. D hovered in the background, just out of camera range, his presence defining the edge of the frame.

Used to be that rap stars wore loose jeans, sideways Yankees caps, and a snarl. Bodyguarding was more about protecting them from themselves than keeping them safe from others. Wasn’t it a decade ago that Jay was on the front page of the

Daily News

, accused of stabbing some kid for bootlegging his CDs? He was a public enemy spawned from the darkest reaches of the jungles of Crooklyn. Now Shawn Carter was a king of New York, and as mainstream as Sunday afternoon baseball.

Jay escaped the flashing cameras and walked toward the Boathouse, a scenic outdoor restaurant/event space off Fifth Avenue in Central Park that was the site of a huge charity bash this balmy summer eve. A $1,000 ticket ($25,000 for a table), a nice tax deduction, a fat goody bag, and maybe a boat ride with a celebrity (who’d do the rowing) made this a well-heeled, upscale crowd.

D didn’t know who or what they were raising money for, but he could see it must be something “in the hood” since hip hop heavies and Upper East Side swells were clinking glasses and recklessly eyeballing each other. Diddy. Andre 3000. Andre Harrell. Q-Tip. Russell Simmons was absent only because he was in St. Louis running one of his Hip-Hop Summits with Nelly. (In addition to raising awareness about the pitfalls that could affect black youths, the summit worked as soft promotion for their respective clothing lines.) Someone had resurrected Fonzworth Bentley for the affair, and he spun his umbrella and pursed his lips for the amusement of the blue-haired and pale-skinned.

D was outfitted in black, as was his custom, from his Hush Puppies loafers to his DKNY suit and Gap T-shirt. He settled in behind a table at the rear of the Boathouse, where Jay was parlaying with two fortyish Wall Street types. They were hyping him like crazy on a new energy drink, hoping to entice him to invest in and endorse their “can’t miss” product. They wanted to call it Sparkle, suggesting a supple bling effect from the drink. “It’s an aspirational beverage,” one was saying earnestly, “like hip hop is an aspirational culture.” One in every hundred cans would contain a piece of faux bling, while every ten thousandth would have a real tiny diamond. Jay listened politely, nodded, and took the odd puff on his now lit Cuban.

D stood back, amused by the two white pitchmen even as he wondered if he should buy some stock the next day. He enjoyed working for Jay cause the brother had cleaned up so nicely.

But his mind wandered. There were no threats in this space, no gunmen in the trees, no niggas sweating Jay for more than a handout or a loan. The autograph seekers in this crowd were likely the offspring of the rich, which meant D let them ask away, knowing somewhere down the line their daddies might be useful to Jay. So, instead of staring down the odd teenager with a napkin and Mont Blanc pen, D stood there recalling his younger days when he’d go to the Apollo to see Doug E. Fresh or Rakim headline or to Union Square where kids slipped razor blades under their tongues, listened to Red Alert spin, and scoped for vics. He listened to the “Old School at Noon” shows on the local hip hop stations religiously, loving when a gem from the Classical Two or the Treacherous Three was dropped. PE and BDP and De La were the stuff that had animated his life when he was young. Now hip hop was big business for him, just like it was for everyone who made records.

His company, D Security, made its monthly nut securing starlets, MCs, A-list events, and the odd after-hours party. In large part it was the remaining glamour of the rap game that kept his little business afloat, though these brothers tended to pay slower than, say, Miley Cyrus’s people. D absently touched the insignia pin on his lapel. It was the only bit of light on his body and it served as an identifier for his employees. A gold

D

against a royal-blue background. Against the advice of many, he’d kept the pin clear of diamonds. For D the button was a classic look, like Adidas’ white shell–toe sneaker and the Yankees’ white-on-blue

NY

. He wasn’t gonna change D Security’s logo like some bad athletic team switching colors to distract fans from their lousy record.

D gazed around the Boathouse, glanced over to where DJ Beverly Bond played the latest hip hop/R&B fusion from a cute, faceless girl group, and thought of the parties in the park and underground clubs and mad passion that had made benefits like this possible, parties where very wealthy white folk conspired with merely rich black folk to turn that energy into lucrative product. It was, D decided, the American Dream manifest. In God we trust—in cash we lust.

D glanced at his watch. In a bit Jay would bore of the business pitches and head over to the studio where his latest mentee, a kid from Baltimore who had a crunk attitude and old-school skills, was laying down some tracks. Jay would probably stay most of the night, listening to how it was going down and adding his very important two cents. It was cool to see the vet work with this kid, but D wouldn’t have to stay that long. One of his men would roll by for overnight duty and D would slide over to his office in Soho to do some paperwork. The accountant was coming tomorrow and he had to go over the books. Thank you, hip hop, he thought. I owe you one.

D

kept his office so dark some people called it his dungeon. Black walls. Burnished-ebony wood furniture. No bright colors. Nothing white save the printouts from his laptop, the envelopes containing bills that filled his inbox, and the skin of an occasional visitor. There was one gold record on his wall. It was for Public Enemy’s

It Takes a Nation of Millions

, a gift from an old friend who had been cleaning out his house in Jersey and passed it on. The office was as big as a good-sized bathroom in a four-star hotel.

D Security’s other room was a fairly large meeting space dominated by a long conference table. Next to it was a setup to recharge walkie batteries, a coffee machine, and a locker where employees stored snacks, clothes, and brass knuckles.

D was writing an e-mail to Russell Simmons about handling security for his next Diamond Empowerment event when he heard a bump against the front door. He went into the little lobby—really just a waiting room with two metal chairs and a framed vintage Run-D.M.C. poster—and opened the door.

Slumped at the foot of the door, wearing a bloody beige trench coat and a blue Yankees cap, was the music critic Dwayne Robinson. Blood oozed from wounds to his chest and arms, and there was a nasty slice to his right cheek. D reached down and placed his hand against his friend’s brown skin, hoping he could somehow slow the flow of blood from his neck. Dwayne’s eyes flickered for a moment and he mumbled, “D?”

“Yeah, man. Tell me who did this.”

“Remix. It’s all a remix.”

“What?”

“Biggie was right.”

“About what?”

“It was all a dream.”

There was no more. No more light. No more words. No more Dwayne Robinson. His soul had departed. All that was left in D’s hands were clothes smeared with crimson spots and a body soon to grow cold.

D had seen death up close way too often to panic in its presence. In fact, it had once been almost as constant to him as air, marking his childhood with ghoulish benchmarks. But that was back in Brownsville, Brooklyn, a lost neighborhood where the streets were saturated with generation after generation of ghetto blood. No one had deserved to die, not his friends, not his brothers. No one who grew up in the Ville was surprised by death. But Dwayne Robinson was a middle-aged black intellectual. A music critic. An author. Why would anyone slash a man like that with a box cutter in goddamn Soho?

D lifted up Dwayne’s bloody palm and his eyes began to water. He was rising to go call the cops when he noticed a square black object clutched in Dwayne’s lifeless right hand. Haven’t seen one of those in years, he thought. It was a black plastic TDK audio cassette, like the kind he’d played a million times on his old Panasonic boom box. It looked ancient.

D knew this was now crime scene evidence but nevertheless pried the tape from Dwayne’s stiffening fingers. Stuck to the side of it was a yellowed label scrawled with

Harlem World Battle

. D went back into his office and dialed 911, all the while squeezing the TDK tape in his bloody hand. Looked around his office and realized he hadn’t owned a cassette player in years. That was another era. High-top fades. Painter’s caps. Four-finger rings. Dapper Dan’s Gucci knockoffs. Dwayne Robinson’s era.

Village Voice

reviews. Critical commentaries. Nationalist rhetoric. All of it “out of here” like that KRS-One rhyme.