The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (27 page)

Read The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism Online

Authors: Edward Baptist

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Social History, #Social Science, #Slavery

In labor camps like Congaree, a few men became “captains” or even “drivers.” But torn between the interests of enslavers, their own interests, and those of their peers, drivers were subject to frequent demotions. Women, meanwhile, usually did not even

have these options. The flattening of the job hierarchy made men, women, and even children roughly equal in the sense that they did the same kind of labor. Many women and children could accomplish some elements of cotton labor just as well as many men. The elimination of most distinctions among the enslaved, and the curtailment of possibilities for independence, put into practice the theory incipient

in the way entrepreneurs sold people at Maspero’s. Everyone had a uniform status—that of cotton “hand.”

17

The product of their labor was also uniform. When the row was finished, the long line of red dirt Ball had turned over disappeared into the sameness of hundreds of identical rows of identical green plants. And the rows stretched on ahead. Simon’s crew finished one set and started another,

still moving at his pace as he carried the lead row. Slowly, slowly, the shadows extended out from the trees on the field’s western borders. The vast gang of “hands” toiled on, all straining to hear the same sound.

At last, as dark settled, the overseer called a halt. The laborers shouldered their hoes and turned for home. Along the way, Ball fell into step with a slow-walking woman. She told

him her name was Lydia. Worn and haggard, she carried a baby on her back in a sling of cloth. The baby had been fathered a year ago, soon after she had arrived from Ball’s own Maryland. They talked as the others outpaced them. But as Ball began to ask her how she had adapted to life in the cotton fields, the overseer’s horn blew. “We are too late, let us run,” Lydia blurted.

Ball arrived back

at the slave cabins just as the overseer finished his roll call. Lydia came toiling up a minute later, with the baby bouncing on her back. “Where have you been?” the overseer demanded. “I only stopped a while to talk to this man,” she said, “but I shall never do it again.” She began to sob. The overseer ordered her to lie down on her stomach. Handing her

baby to another woman, she complied. The

white man pulled up her torn shift, exposing her buttocks and back. Then he drew from his belt the lash he had been carrying folded there all day.

The whip, ten feet of plaited cowhide dangling from a weighted handle, was, Ball realized, “different from all other whips that I have ever seen.” The impression it made would never leave him. Many other migrants reported the same feeling of shocked

discovery. In Virginia and Maryland, white people used cat-o’-nine-tails, short leather whips with multiple thongs. These were dangerous weapons, and Chesapeake enslavers were creative in developing a repertoire of torment to force people to do what they wanted. But this southwestern whip was far worse. In expert hands it ripped open the air with a sonic boom, tearing gashes through skin and flesh.

As the overseer beat Lydia, she screamed and writhed. Her flesh shook. Blood rolled off her back and percolated into the packed, dark soil of the yard.

18

Those who had seen and experienced torture in both the southeastern and southwestern regions universally insisted that it was worse on the southwestern plantations. Ex-slave William Hall remembered that after he was taken to Mississippi, he

“saw there a great deal of cotton-growing and persecution of slaves by men who had used them well” back in the Southeast. Once “the masters got where they could make money[,] they drove the hands severely.” White people also recorded the way that southwestern captivity distilled and intensified slavery. On a sheet of lined notepaper saved by small-time cotton planter William Bailey survives a strange

set of lyrics in the voice of an enslaved migrant, a man moved to the cotton frontier: “Oh white folks, I hab crossed de mountains / How many miles I didn’t count em.” Perhaps Bailey wrote down verses he heard. Perhaps he wrote them as a “darky song” parody. Either way, they tell us what people at both ends of the whip understood as its purpose. “Oh, I’se left de folks at de old plantation / And

come down here for my education,” he wrote. What did the “singer” define as his “education”? “De first dat I eber got a licken / Was down at de forks ob de cotton picken / Oh it made me dance, it made me tremble / I golly it made my eyeballs jingle.”

19

Survivors of southwestern torture said their experiences were so horrific that they made any previous “licken” seem like nothing. Okah Tubbee,

a part-Choctaw, part-African teenager enslaved in Natchez, remembered his first time under “what they call in the South, the overseer’s whip.” Tubbee stood up for the first few blood-cutting strokes, but then he fell down and passed out. He woke up vomiting. They were still beating him. He slipped into darkness again.

20

Under the whip, people could not speak in sentences or think coherently.

They “danced,” trembled, babbled, lost control of their bodies. Talking to the rest of the white world, enslavers downplayed the damage inflicted by the overseer’s whip. Sure, it might etch deep gashes in the skin of its victim, make them “tremble” or “dance,” as enslavers said, but it did not disable them. Whites were open with those whom they beat about the whip’s purpose. Its point was the way

it asserted dominance so “educationally” that the enslaved would abandon hope of successful resistance to the pushing system’s demands.

“Their plan of getting quantities of cotton,” recalled Henry Bibb of the people who drove him to labor on the Red River, “is to extort it by the lash.” In the context of the pushing system, the whip was as important to making cotton grow as sunshine and rain.

That’s exactly what Willie Vester, a Mississippi overseer, told his friends back in North Carolina. He hoped to ride back home for a visit on a nice new horse, sporting a suit of fine clothes. To do so, he needed to “make a little more [money].” The way to do that was to “walk over the cotton patch and bring my long platted whip down and say ‘who prowd[,] boys[?]’ and see a fiew more bales made.”

Likewise, in 1849 a migrating North Carolina planter hired a “Mississippi overseer” to ensure that his “hands” would be “followed up from day break until dark as is the custom here.” The overseer would drive each “fore row” in a vast and easily surveyed field, and he would “whip up” those who fell behind. All that pushing, the owner calculated, would force “my negroes [to do] twice as much here as

negroes generally do in N.C.”

21

Finished with beating Lydia, Hampton’s overseer turned to Charles Ball, who stood frozen on the edge of the lamplight. “When I get a new negro under my command,” he said, “I never whip at first; I always give him a few days to learn his duty. . . . You ought not to have stayed behind to talk to Lydia, but as this is your first offence, I shall overlook it.” Ball

nodded mutely and “thanked master overseer for his kindness.” As he chewed his cornbread, he reflected on his new reality: “I had now lived through one of the days—a succession of which make up the life of a slave—on a cotton plantation,” he later wrote.

22

IN THE COURSE OF

surviving his first day, Ball had discovered the new pushing system: a system that extracted more work by using oppressively

direct supervision combined with torture ratcheted up to far higher levels than he had experienced before. Between 1790 and 1860, these crucial innovations made possible a vast increase in the amount of cotton grown in the United

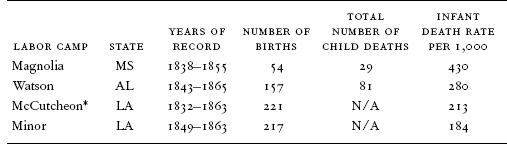

States. They did so at an immense human cost, which could be calculated in many ways. We could count those who caught malaria in the fields of a more intense disease

environment, or those who died young, their bodies malnourished by insufficient food and intense labor. The rate of infant mortality in the new slave labor camps was extraordinary: one of every four children born died before reaching his or her first birthday. This is five times the rate of present-day Haiti, the same as the rate that would have been found in the most malaria-infested parts of nineteenth-century

West Africa or the Caribbean (see

Tables 4.2

and

4.3

). And every burst of forced migration produced a decrease in the average life expectancy of African Americans, not just for infants, but for the whole population.

23

TABLE 4.2. INFANT DEATH RATES ON SELECTED SOUTHWESTERN SLAVE LABOR CAMPS

Sources:

R. C. Ballard Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Henry Watson Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; Richard H. Steckel,

The Economics of U.S. Slave and Southern White Fertility

(New York, 1985).

*

In the McCutcheon documents, only 14.6 percent of all recorded infant deaths occur in the first twenty-eight days after birth, whereas other statistics suggest that a rate of 50 percent is much more typical. This fact, in turn, suggests a substantial under-enumeration of both births and deaths. The real infant death rate was probably about 350.

But other costs cannot be measured. Although Ball had been able to keep up with Simon, he foresaw that the pace of work on coming

days would be difficult and unvarying. He could tell that his clothes would wear down to rags. He also clearly ran the constant risk of suffering violent, humiliating assault. Ball had not been beaten since he was fifteen. Back in Maryland, he had been what owners called “a well-disposed negro” who tried to build a life within the system. Anyway, the pathological bullies that white supremacy

bred in such high numbers preferred easier targets than someone as large and strong as Ball. But he could see that on the Congaree, if white folks thought that doing so would result in more cotton, they would find a way to bend even the toughest black man to the new bullwhip.

24

TABLE 4.3. COMPARATIVE INFANT DEATH RATES

Sources:

*

Jack Ericson Eblen, “Growth of the Black Population in Ante Bellum America, 1820–1860,”

Population Studies

26 (1972): 273–289.

**

Richard H. Steckel,

The Economics of U.S. Slave and Southern White Fertility

(New York, 1985), 88–89.

***

B. W. Higman,

Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807–1834

(Kingston, Jamaica, 1995), 319.

†

Actuarial estimate for 1830–1860 made in 1895. See Michael R. Haines and Roger C. Avery, “The American Life Table of 1830–1860: An Evaluation,”

Journal of Interdisciplinary History

11 (1980): 11–35, esp. 88.

††

Central Intelligence Agency,

World Fact Book

,

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

.

Intimidated, Ball strove hard in the days that followed to labor at the torrid tempo of the southwestern pushing

system. By the time July rolled toward its close, he had begun to outpace Simon. The “hands” had chopped weeds from every cotton row three times over, and now the plants were “laid by”—tall enough to shade the rows and keep down the growth of weeds. Now Ball began to look around. One Sunday, exploring, he found a body dangling in the woods—a runaway, despairing of escape, unwilling to return. Through

his own long march he had stuck to his resolution to stay alive for something better to offer itself. So now, as he hilled sweet potatoes, he calculated how many he could carry in his shirt if he slipped off for Maryland. As he pulled leaves from the corn stalks, fodder for the livestock, he looked at swelling ears and mentally mapped the months when they would be ripe on the stalk on the banks

of all the rivers he’d counted and named on his route south.