The Heart Has Reasons (10 page)

As soon as the Germans occupied our country, my husband began resisting. He was from the province of Friesland, and the Frisians are legendary for standing up against tyranny. They’ve always been resisting—whether it was the Spaniards, or the Saxons, or all the way back to the Roman invasion by Julius Caesar. True to his roots, he refused to submit, and he held very strong convictions about how people should be treated.

He actually started a resistance movement here. He recruited people by scrawling messages on the sidewalk. I didn’t know everything that he was doing—it was better for me not to—but when the Nazis started rounding up the Jews, the caretaker of the local synagogue gave him some addresses of Jewish children and adults who needed to dive under. After that, he went out into the farmlands and tried to locate households where these people could go and hide.

One night he came home downhearted, and said, “No matter how much I talk, they always ask if

I

have taken in any Jewish people. And when I tell them no, I don’t get anywhere.” I said, “Maybe we should try it ourselves—that would convince them.” He agreed, and that’s the way it started.

We decided to take in a friend of some friends: a diamond cutter from Amsterdam. Our friends couldn’t take him themselves because they lived in the back of a store, and there were too many people coming in and out. Still, our house was not ideal: we shared a wall with our neighbors, and everyone knew everyone on this street. But we said we would be glad to meet him. Immediately, it sort of clicked. It has to click somehow; otherwise you’ll never be able to get along with someone in the long run.

After we had taken in this Jewish man, my husband had more success finding safe addresses for the other people on the list. Then, a few months later, a doctor who lived in a nearby village told us about a

certain couple who were roaming around in the countryside with their belongings on their backs. Could we help them? We told him he could give them our address, and they eventually made their way to us. They looked very tired and they smelled of manure from having hidden in a pasture for a couple of days. Their clothes were rumpled, and they still had pieces of straw in their hair from having slept in a haystack. We had only expected two, but they had a daughter also—a thin girl with watery blue eyes, and a wan face.

Now that we had four onderduikers in the house, we became very vigilant. It was always, “What was that sound?” “Who’s at the door?” We constantly had to consider how things looked from the outside. Across the street was a butcher, and he had customers all day long—anything suspicious would surely have been noticed.

Sometimes, when the onderduikers needed to come out of their rooms to take a break, we would put a sign on the front door that said DIPTHERIA. This was because the Germans were very afraid to enter any house where someone had an infectious disease. Then we took the girl, who was very frail and pale, and sat her by the front window. She was our poster child to show that there really

was

sickness in the house.

The onderduikers had to stay inside all the time, except, once a day, one of them could go down to the cellar to listen to the broadcast of Radio Orange from England. They could never, ever, go out on the street.

It was forbidden to have a radio, and you could get into even more trouble if you were caught listening to the BBC. So we kept the radio in the cellar, and each afternoon at four o’clock one of the onderduikers would open the trapdoor and climb down there. The ten-minute Radio Orange broadcast was all crackly, but it meant a lot to us to be able to get news from the outside world.

Once, the neighbor’s child was ill and a doctor had come over to make a house call. When he was finished, he left from the back, and just as he was walking along the side of our house, one of the onderduikers raised the trap door, and climbed out of the cellar! I saw the doctor take a look at him, and then stride away. What should I do?

I went running after that doctor. I didn’t know what to say, because by saying anything I’d already be taking a dreadful risk. But if I didn’t speak to him, I’d never know whether he could be trusted. He turned around, gripping his black leather bag, and fixed me with his deep-set eyes. “My, my, what a doctor sees. I see so much.” Then he walked away. It was horrible.

We had a few sleepless nights, but, in the end, nothing happened. I

later realized he was trying to reassure me, but he couldn’t say anything either. Those unexpected crises were the most trying, and they would happen quite often.

A few months after we had taken in the couple with the straw in their hair, we decided to take in another couple. We had learned so much about the plight of the Jews from this first family that we felt that we had to do more. This time my husband went by train to meet our new arrivals at the Amsterdam Central Station. Again, he expected two, but he found they had a son and daughter. He said, “We only have room for two adults.” The mother started to cry so hard that Wopke said, “Don’t worry. We’ll start out with you and your daughter, and your husband and son can come later.” And that’s what happened.

Occasionally we thought that perhaps we were taking in too many, but everything went fairly well. Their daughter Ellis called this the “chewing gum house,” because you could always stretch more people into it. So eventually we had two families, plus the first man, plus myself and my husband. And our three children—but they never knew.

Even Hetty Voûte doesn’t understand how we could have kept the onderduikers a secret from our daughters. Part of it was the precautions we took. No matter what room they were in, the onderduikers always kept the doors latched from the inside with hooks and eyebolts. And, of course, they had to keep very, very quiet.

The children were never supposed to see the onderduikers, and they didn’t know about them for three years. I think our eldest daughter saw someone on the stairwell once, and she may have heard things in the house. But she wasn’t eager to solve the mystery—I think she liked to fantasize about what was going on.

Some people have suggested that my girls knew but must have understood that it was not something they could speak about. Or that maybe they thought that if we

knew

they knew, it would worry us, and then we might ask the onderduikers to leave. Well, that may have been true in some households, but not in ours. Only by living here could you fully understand what our arrangement was like.

I must admit that it wasn’t very good for my girls. For instance, they all had to sleep in one small room on one mattress. At night, we would put a chamber pot in the room, and lock them in. If one of them needed us, she would have to bang on the door, and then I would get up and unlock it—after I made sure that the hallway was clear.

At six in the morning, the onderduikers who were upstairs—in the front room and the back room—would go downstairs to the room off

of the hallway and spend the rest of the day there. That was where the family of three slept—they called it their Hilton. The three people who slept on chairs would then go into our bed so that they would be able to rest properly on a real mattress. (They used to tie chairs together and put a board between them to get a bit of length.) In the upstairs back room was the family with the two children. The parents slept in a daybed that was uncomfortable, so they too would go into my bedroom later in the day to rest. It was a little like a game of musical chairs every day, only with beds.

In the downstairs hallway there were three doors: the room where the onderduikers would be during the day, the door to the kitchen, and the door to the toilet. Every Saturday my father would come to visit. Once he was heading for the toilet and, by mistake, he opened the door where the onderduikers were. There were eight people sitting around a table! He immediately closed the door.

After he left, I went into the room and visited the people. Their faces were so long that you could have slipped them through a letter slot. When they told me what had happened, I was sure my father would never say a word. But I was sorry that he knew about it, because now he would worry about us. In those days, knowing such things could be a very heavy burden. After the war, he told me that he had understood immediately that they were onderduikers. Later we learned that where he was living—with my sister and her husband on their farm—they also had hidden three Jewish people.

Once, during the war, a woman I knew came to the door and asked very nervously if we might possibly take in an onderduiker. I said that we didn’t have any room, since the house was so small. I just stood there and said that, not able to explain that there were already three people hiding in the front of the house, and five people stashed in the back!

You might think it was a lot of work to take care of eight extra people. But the onderduikers pitched in: the women did a lot of sewing, and they would knit and crochet using yarn from old sweaters that they dyed to look like new. They all helped with the cooking—peeling potatoes, cutting vegetables—and also with the mending: for instance, the diamond cutter would fix the children’s shoes.

There was a heater in the back room, and in the winter, after our children had been playing outside, I would take them into that back room to warm up. The onderduikers in that room knew when the children were coming, and they would crouch under the table, which had a tablecloth that reached almost to the floor. So they would just stay under there and keep really quiet while the children came in to

warm themselves. The onderduikers loved that little bit of contact—they were very, very excited to have the children come in. And the children would be dressed in the clothes that the onderduikers had made for them. They all delighted in seeing the children gambol about in those gay clothes.

It would have been very hard to get enough food for everybody, but in addition to our own food coupons, the Resistance gave us food coupons that they had spirited away from the civic offices. There was also a gentleman from Amsterdam who always brought over food coupons for the family of four. Most days we would put potatoes onto the stove at two o’clock in the afternoon, and when the food was ready, we would eat in shifts. Then at the end of the night, I piled up the dishes in the sink, and two of the onderduikers would come out of their room and wash them.

Once the children were asleep, the onderduikers all came out and we’d sit around downstairs and talk about everything under the sun. Often we’d discuss the Bible passages that Wopke had read to them earlier in the day—it was part of his routine to slip into the back room before the children got home from school and read them something from the Old Testament. So in the evenings, we had some great conversations about Abraham and Sarah, Joseph, Moses, Daniel, and the way God works in the world.

At other times, we were frivolous: I remember a night when we talked about nothing but food and cooking. One of the women told us about a cake recipe that called for a dozen eggs! We were tantalized beyond belief to hear her description of the fluffy whipped egg whites and layers of chocolate, topped with powdery sugar.

We all used to tell stories, but especially my husband. He would tell tall tales, and could really plop it on. One of the men used to sell cigars, and the other one had also been a salesman. Together they had an endless supply of traveling salesman jokes. I can’t remember ever laughing so hard as during those evenings. We would all sit there and just shake with laughter until Wop would make us quiet down. Or he’d play really loud on the barrel organ to cover up the sound. My husband was a very good musician. He would play some lively tunes, especially on evenings when we really needed to laugh out loud.

We kept our spirits up mostly through positive thinking. The onderduikers had so many worries, and being cooped up all day didn’t help any. We all had to deal with quite a bit of doom and gloom, and there were some very hard periods. If you didn’t think positively, if you didn’t

convince yourself that you were going to make it, then it was almost impossible to keep on.

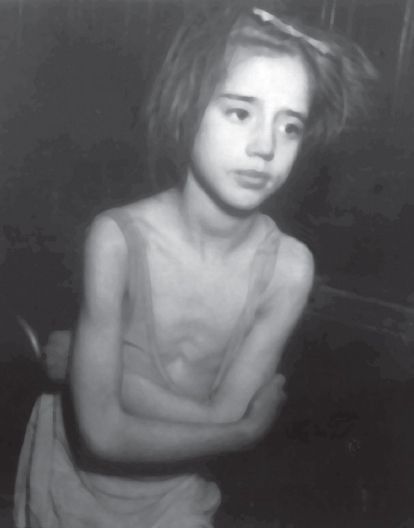

Dutch girl during the “Hunger Winter.” Photo courtesy of the

Netherlands Institute for War Documentation

Towards the end of ’44, we had the “Hunger Winter.” We didn’t know it would only last for the winter; it slowly closed in upon us and after a while we couldn’t imagine not living in hunger. Things had not gone well for the Allies at the Battle of Arnhem, and, though the south would soon be liberated, the land where we were—north of the great Rhine and Waal rivers—remained under tight German control. By that time, my husband couldn’t show his face on the street anymore because of the forced labor roundups and his connections with the Resistance, so he was hiding in the house also. Not only was food scarce, but there was no coal, and you couldn’t get wood, so it was very difficult to stay warm, let alone to cook.

I would go on my bicycle to other villages and bring back milk and eggs. When these were no longer available, we ate sugar beets and tulip bulbs. But the day came when we had no food at all. We didn’t want to worry the onderduikers with this grave news, but finally my husband asked all of them to come sit around the table. “We really don’t have anything to eat anymore,” he said. Of course, when you have news like that, there’s always someone who caves in completely. I looked around at the downcast faces and said, “We may not have food, but there’s still plenty of water. If we had no water, then we’d really be in trouble.”