The Heart Has Reasons (8 page)

Sometimes you felt guilty when you were with someone who had lost a husband, or a child, or parents—or everyone. More than 90,000 women perished in Ravensbrück, so you’d ask yourself, why did I survive? Over the course of the war, two of my brothers were arrested and sent to the camps. One had been in the Dutch East Indies, and ended up in a Japanese camp. My other brother who was doing espionage was caught half-way across the North Sea on his way to England, and sent straight to a German camp. We all came out of the war alive, so we were very lucky. But you’d ask yourself, why is my family so well off?

That same nephew who told my parents that I had come out of Ravensbrück returned to the Netherlands to find that all his brothers had been killed. That’s how life was then. But I don’t really feel guilty over having survived. I’m glad about it. It could have been quite different. Often I think that each day is a gift.

By the time I made it back to the Netherlands to live, it was April of ’46. In a way, I had forgotten about my old life. When the war started I was twenty-two, and by the time I returned I was twenty-eight. But it wasn’t

until I got home and started looking around that I realized how many years I had lost. I planned to finish my education, but then I met a very handsome young man who had been in the Japanese camps. I thought, well, I’m not going to get involved right now; I need to concentrate on my studies. You see, he was soon going to leave for the Dutch East Indies, and he wanted me to come with him. But when I went back to college, I found I was not able to read the books anymore. It was too abstract, too small. I just couldn’t relate to it.

Meanwhile his passage to the Dutch East Indies was delayed for three months, and then for another three months. After that time I thought, well, it could be great to live with him in the Dutch East Indies, so we got married and soon afterwards set sail for the Malay Archipelago. And that was very exciting, for the people there wanted to be free, and our country was telling them that they were not ready for it. So they began to fight for their freedom. I was on their side, although most people said, “It’s our country, and we made it great, so it should remain our property.” But I knew what it is like to not have your freedom, and that’s what they had been going through for ages.

While in the Dutch East Indies, we had four children, one after another, and I thought being a mother was

marvelous

. By the time our youngest was born, the native people had won their struggle and the country was renamed Indonesia. However, a chasm began to develop between my husband and me, even though he and the children were my whole life at that time. You see, I had stopped talking about what had happened to me during the war. At my final medical checkup before I left for the Dutch East Indies, my doctor had said, “Forget about all that as fast as you can.” So as I closed the door behind me to leave his office, I also closed the door of my memory. But later the memories started returning, and I couldn’t keep them back.

For my husband, however, it was an obsession

not

to talk about what happened. I began to realize that he had been much more wounded in the camps than I had. You could never say a single word—he did not want to hear it, and he would never speak of it. But as the children got older, I simply

had

to discuss it with them. To not be allowed to do so was very difficult, and, in the end, we went our separate ways.

I can see now that he was absolutely right to find another woman. There was so much I wanted to talk about, and he was just shutting down more and more. I think that now I would understand him much better. Perhaps I should have handled it differently, but I didn’t know enough then. Kierkegaard said that life must be lived forward, but can only be

understood backward, and that’s true.

The Germans put you through so much. How do you feel about them now?

For a long time I was very angry, but now . . . I always tell people, “I read as many German books as English books, and I love German literature and poetry.” But an old feeling sometimes comes over me. When we were going on holiday and our train had to stop in Frankfurt, a German lady started talking to my youngest son. It was like she was some overseer from the camps, and I felt so sick that I threw up. And sometimes if I’m on the highway and there’s a German driving too close behind me, I have to pull over to the side of the road to calm down. It’s something I can’t master, that feeling.

But, for some reason, when I think back to the war, it never makes me feel bad. I’ve never even had a nightmare. Sometimes I think I’m not a deep-feeler, or something. I don’t know.

I’d have to say I’m happy, but what is happiness? Cows are happy. During the war, we were happy because we did something. I think that if we had not done what we did, we would have been unhappy about it our entire lives. My grandchildren say, “We don’t know if we would have done the same.” Yes, but we had a

chance

to do something!

Overall, our group saved nearly 400 children. Many more, of course, needed our help, but you simply did all you were able, and you couldn’t stop with it. It was work—hard work. Also, the families who took in the children needed help to be able to afford the additional expense. So I would go around begging for money.

I think it’s true that many Dutch people don’t want to talk about the war because they are ashamed of how they acted—or rather, didn’t act. When I came back in ’46 I knew a lot of people who were absolutely not interested in hearing my stories. Looking back, I think they may have been uneasy over not having done anything. And I can understand—the ghosts of their choices must have haunted them.

And then there were the people who believed that if you did the right things in life, all would be well with you. When they heard that the Jews were in trouble, they thought they must have done something to deserve it. That’s a foolish, foolish way of thinking. But that is the way a lot of people thought, and that’s the curse for the Jews: they always say it’s their own fault. And that goes back to the original accusation that the Jews killed

Christ, and the way that was used as a justification for killing the Jews. And that’s what Christianity has done. It’s terrible—all through the ages!

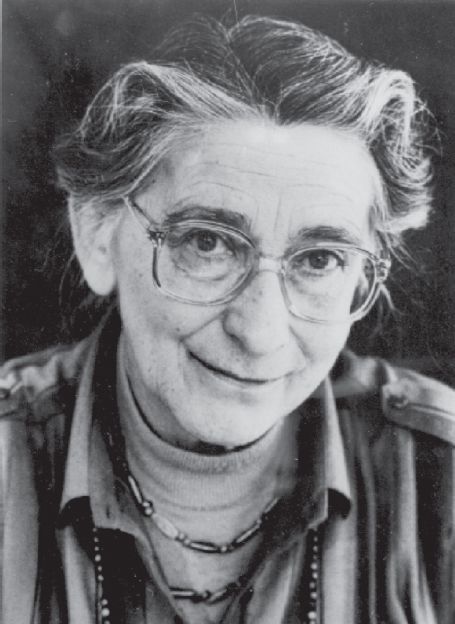

Hetty Voûte as an elder. Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters’ House (Beit

Lohamei HaGetaot), in Western Galilee, Israel.

I was brought up Remonstrant—it’s a very free-thinking Protestant belief that goes back to the 1600s. And Gisela, my friend, was nothing. Atheist, absolutely nothing. When I was growing up, my mother always read to us from the Bible. I’m very at home with it—such wonderful stories. In prison I was able to have a Bible. Once while I was there, I sent Piglet a letter in which I quoted many things from it. She wrote back, “That’s all well and good, but everybody already knows it, and you didn’t have to get it out of the Bible.” Still, when we were liberated from Ravensbrück, the official who talked to us also blessed us at the end, and we both liked that very much.

I think it’s marvelous to have real faith, but I can believe no longer. Not a sad thing, but it’s simply the way it is. I must say though that sometimes I have prayed very deeply, because it helped me. Yet I knew there was no one there, at least not in the way that some believers imagine. Take the Roman Catholics: they kneel before their saints and light candles and such. Marvelous if you believe in it, but to me it’s all superstition. Nevermind though—it’s beautiful. Were you raised with the Bible?

A little bit. My grandparents were religious Jews, but my father lost any faith he may

have had because of the Holocaust.

I can understand.

He thought that if there was a God, He wouldn’t have allowed it.

Yes, but what is your idea of God? I once had a friend who came to me and said, “I’ve lost my faith in God.” After she explained, I said, “Oh, I haven’t believed in

that

God for years.” I think it’s so terribly difficult to know what God is. What do you want from God? Is He responsible? Where is He? Inside you, I think.

So many people went along with what the Nazis were doing. How did you grow up to

be a person who defied them?

I think that both of my parents were rather independent. They were never impressed by what other people thought. They always went their own way and thought their own thoughts, and that’s the way they raised us. My father took a strong stand on certain community issues. He didn’t care what kind of flak he got. And when I went to school, I was the same way.

I think my family was an important factor in my being able to face the camps the way I did. I had a marvelous youth. I had a strong mother, and a very special father. And five brothers and a sister. We really had a fantastic home. The same was true of my friend Gisela—we both came from happy families.

It occurred to me to ask Hetty whether her parents had taken in any malnourished

German and Austrian children following World War I. Miep Gies, who was one

of the hungry little girls sent to the Netherlands through this humanitarian program,

speaks of it as a crucial factor in her later decision to help Anne Frank and her family.

The experience taught her that one can be “a good little girl” and still suffer for no reason

at all, and also that there are people who understand, care, and are willing to help.

When I mentioned the post-World War I program to Hetty, her face lit up.

Oh, yes, we had them. For years after the Great War, there were little girls who came, and they became our friends. I was still very small, but sometimes my mother would tell me that a train was coming with starved little girls and boys, and that she would go to a big room, and Mother would get to choose which one she wanted to take home with her. She told us a story that once she went up to a small, black-haired girl, and asked, “Do you like playing with dolls?” She shook her head no. “Do you like to embroider?” Again she said no. “How about cooking?” “No!”—this time she spoke up. Then my mother said, “You are

exactly

like my own children—come home with me.” And that little girl became a great friend of ours,

and, afterwards, her family also came to this country, and we had other girls as well. Yes, we often had children come like that. They would stay for months. There were already seven of us—one or two more made no difference.

And that’s the way it always was in my family. When somebody needed help, we would help them. In those days, there were no real social services; it always came down to someone helping in a very personal way. I remember that there were several families nearby with hardly any money. Every weekend my mother would say, “You just take these envelopes, and go there, and there, and there.” And when Sinterklaas came, we were always preparing baskets of food, and we would bring them around to those people. It was just something I grew up with.

Later, all my brothers were involved in the Resistance, but I didn’t realize how unusual that was. After the war, someone told me that only a few people had been working against the Germans. I said, “That’s nonsense. Wasn’t everybody doing it?”

What kinds of activities are you involved with these days?

I run a foundation with my children to help Icelandic horses. These beautiful horses are brought here and kept all cooped up, which offends them, for they need a lot of space. So then they become bad-tempered, and the owners castrate them to make them less aggressive. My children and I worked it out with the minister of agriculture to use certain grasslands, so now the young foals can run free, and they’re very happy. If they’re not confined when they’re young, they’ll be fine after that, so we keep them there for four years, and then return them to their owners.

We also have a special tract of land for the retired horses. They can spend their old age there after they’re no good anymore for riding or competition. They just canter about and have a lovely time playing together. It’s

marvelous

to watch them. Icelandic horses come in so many different colors: chestnut, bay, palomino buckskin, smoky black, silver dapple, blue dun. At first, people said, “If I give you my horse, I’ll never be able to get my hands on him again!” But that’s absolutely not true. These horses only don’t like people when they’re forced to be around people all the time. Once you let them run free, they’ll come up to you and be very friendly. It’s people who make them nasty—as we always find everywhere.