The Heart Has Reasons (26 page)

How did the SD find out where Krijn was? Someone must have told them, but it wasn’t Esmée, as some people later claimed. True, Esmée played a singularly tragic role in the Dutch Resistance: she was considered Krijn’s “right hand,” and because she spoke perfect German and had the looks to match, Krijn had asked her to do a little spying, to try to infiltrate a certain Nazi social circle. But then she fell in love with a German officer and many people died as a result—including herself. But I don't want to go any further into that story . . . it’s too emotional for me. I’d rather remember Krijn: he was a fantastic man.

You know, for most of the war, Hansje and I were engaged, but one day I said, “Let’s get married.” There was a great sense of danger at that time: when you said to your friends in the Resistance, “See you later,” you couldn’t be sure that you really would see them later. We didn’t

know how the war would turn out, we didn’t know if we’d live to see the end of it, but we wanted to be man and wife. So we made our wedding plans and tied the knot right in the thick of our Resistance work. It was the only time during the occupation that all the members of the Amsterdam Student Group and the Utrecht Kindercomité were in the same room together, except for Hetty and Gisela, who had just been arrested.

The Wedding of Pieter and Hansje. This was the only time during the war that members of the Utrecht Kindercomité

and the Amsterdam Student Group were together in the same room (with the exception of Hetty and Gisela.)

We wanted so much for Krijn to be there too, but he felt it was too dangerous for him to come. And then just a few months later he was killed—on the very day of our meeting.

After the war, Hansje and I named our first child after Krijn. That’s my eldest son, the one I still work with today.

How involved were Holland’s churches in your rescue network?

The churches played a big part in it, because the pastors urged the people to participate. In Sneek, there was a committee that included a Mennonite minister, a Dutch Reformed assistant minister, and a Roman Catholic priest. That was unheard of at the time, because Protestants and Catholics didn’t have anything to do with each other. And on top of that, the Dutch Reformed assistant minister was a woman. But to save the children they came together, and they did a wonderful job—although, after one year, the Catholic Church moved the priest to another town.

Did the Catholic authorities not want him to help with that cause?

Absolutely not. I have no religion, so I can speak impartially: The Catholic Church in Holland did a wonderful job during the war. I once saw a letter that Archbishop de Jong of Utrecht had sent to all the bishops in Holland. I can’t believe he wasn’t immediately arrested because it was a letter with his official seal asking them to take up a collection to help the Jews. If even

one

person had given that letter to the Germans, that would have been the end of Archbishop de Jong.

Another reason I can say that the Catholic Church did such a good job is because they didn’t baptize the Jewish children or try to convert them. You know how it is—there’s always someone overanxious to win another soul. My present wife is a Jewish woman who, as a young girl, was hidden for awhile by a Catholic family. She went along with their religious practices, and it would have been very easy for her to take on that religion. You see, if a Jewish child didn’t look Jewish, the host family could make up a story; they could say it was a cousin who had been bombed out of Rotterdam or something like that. Then that child could do everything with the family, and there was no need to hide. But it also meant going to church with them, because otherwise it looked suspicious. And, anyway, the child would want to go. After all, it’s quite a show, the Catholic Church, eh?

But the churches didn’t try to baptize the children—the Archbishop had told them not to. I think that was very, very decent of him. On the other hand, the Pope, in general, behaved very badly during the war. He was one of the few who could have really done something, but he didn’t speak out. But the churches here, both Catholic and Protestant, were absolutely against the Nazis, against the occupation, and very much in favor of trying to protect the Jews from persecution.

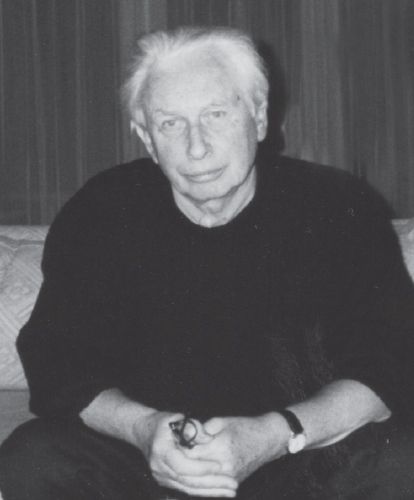

Pieter Meerburg as an elder.

You know, one of the things I’d really like to see happen is for Yad Vashem to start honoring

Jewish

people who helped in the Resistance. Many people think the Jews went to their deaths like sheep to the slaughter, and that’s not true—it’s absolutely not true. I worked closely with many Jewish people in the Resistance, and I can tell you, they took much greater risks than I did. People like Walter Suskind and Felix Halverstad really behaved very bravely, and with a double risk: they were Jewish

and

in the Resistance.

Felix survived the war, and he remained one of my closest friends until his death a few years ago. Walter Suskind, until the end, kept on trying to save people. And what about my friend Max Dikker, who, even though he looked very Jewish, went all over Amsterdam trying to hide children, and doing all kinds of things? I think it’s completely wrong that Yad Vashem only honors non-Jewish people. I hope they will change their minds on that, because the world really needs to know that the Jewish people

did

resist. Of course, it was not a mass, open resistance; that wouldn’t have worked. But if some of the stories of what the Jews did to save themselves and others during the war became known, I think that many people would be very astonished.

On the other hand, the Jewish Council—with the exception of men like Walter Suskind and Felix Halverstad—was the biggest mistake that the Jewish people in Holland ever made. Absolutely. And that we can say now, now that we know everything. I mean, it’s easy to say they made a mistake; most of them agree they made a mistake.

The Jewish Council did their work with the assumption that if they could keep things in their own hands, it would be better than if the Germans were doing it. But that was not the case, because if the Jewish Council said, “Report to Westerbork,” it was worse than if the Germans said “Report to Westerbork.” Though the Germans had

all the power, and were, you could say, holding a gun to their back, they could still have found ways to resist, or at least purposely done a bad job. I mean, after the war, Eichmann said about the Netherlands: “There, the transports ran so smoothly that it was a joy to watch them.” Those transports all operated in coordination with the Jewish Council—every person on them was selected by the Jewish Council. Instead of being an institution that subverted the plans the Nazis had made to deport the Jews, it helped to get them into the concentration camps as quickly as possible. Now, that was completely the wrong approach. In the face of unjust authority, they should have been saboteurs, not servants.

The two men at the top were David Cohen and Abraham Asscher. Cohen had been a professor of classics—he was a pipe-smoking intellectual type—and the other was a businessman, a diamond merchant. The professor had more power, because the other guy really looked up to him. And I can tell you something that is unbelievable: the one non-Nazi who really threatened me during the three years that I was in the Resistance was David Cohen. When he learned I had taken a certain child from the Creche, he said, “If you don’t bring him back, I’ll turn you in.” I don’t usually talk about this in the Netherlands because I’m very close to his daughter, Virrie. She’s a wonderful woman, everything her father wasn’t—she was a childcare worker at the Creche, and helped to smuggle out the children. We’re such good friends, but in my opinion, one of the things that must really be looked at in the coming years is the terrible role played by the Jewish Council.

Let me say this: when it started out it was all right—Asscher and Cohen had determined never to do things that were “contrary to Jewish honor.” Some say they bent so that they would not break. But it came down to self-preservation: if you worked for the Jewish Council, you and your family were exempt from deportation. So they did what the Germans wanted in order to hold onto their deferments. But that, of course, turned out to be a ruse: towards the end of the war, nothing could save you. Once the people on the Jewish Council had served their purpose, they, too, were sent to the camps—including Cohen and Asscher.

There were so many children who needed to be saved, but we could only save a few of them—we knew that. By the end of the war, about

350 children had passed through our hands, and several other groups were able to rescue about the same number, bringing the total to about 1,100 children. But what’s that out of 140,000 people? It’s infinitesimal; it’s not enough. One of the things that I regret very much is that we were unable to do more. I mean, we really worked very hard at it, as hard as we could—it was all we did for three years. But still, I think it’s such a tragedy that so few people helped. It’s a shame for humankind. Half of the children should have been saved, or, if not that, at least a third of them.

But one of the things I’m absolutely sure about is this: the people who were rich, the ones with many assets, didn’t want to take a chance, didn’t want to participate in the Resistance. I know of only one man, Dr. Wetzlar, who was an exception. He was a multimillionaire who had come from Germany. He always said he was one-eighth Jewish but, to be honest, I think he was at least half. But he didn’t consider himself a Jew, and he never wore the yellow star.

The man did

everything

, he did everything; he put his whole fortune on the line. Not only did he give money, but he had warehouses that were packed with arms for the Resistance—the man really did everything. But he was the only one like that who did it. He survived the war, and we became great friends. He was a wonderful man.

Why didn’t more people help? Well, in the case of the people who had money, I think it was greed: they didn’t want to lose their money. But people had other reasons, too—they were very afraid, and they had all kinds of reasons. But one thing I know for certain is that you could find far more addresses among the common people.

We would go to these large families in the north who had very little, and they would say, “Oh well, one or two more children won’t make any difference. Just send them along.” My present wife lived with one of these families; as a child, she was hidden with one of the poorest families of Friesland, really one of the poorest families. I went over there for dinner a few times, and all they had to eat was a kind of soup with potatoes in it. This is before the “hunger winter,” but still, they kept her for six months. Those are the kind of people who were really wonderful. But the ones with money didn’t want to take the risk.

Do you think many people regret that they didn’t do more to help the Jews?

There are a few people who feel ashamed, but I think, in general, if you didn’t care during the war, you’re not going to care after the war. I wish

I could give you a different answer.

Cornelis Suijk of the Anne Frank Center tells a story about Karl Silberbauer, the

policeman who arrested the Frank family. About thirty years after the war, Suijk

located him in Vienna and found that he was employed by the police force there. When

asked about the Frank family, he remembered the arrest but seemed to have no pangs of

conscience. He’d even bought the diary of Anne Frank but dismissed it as “kid stuff.”