The Hemingway Cookbook (24 page)

Read The Hemingway Cookbook Online

Authors: Craig Boreth

Proportions of things vary according to the cook’s personality, but the standard rule is that the total vegetables add up to half—about half—as much as the main ingredient

.

Fry the vegetables briefly in oil (add the beansprouts last), add the chief ingredient, to heat it, pour on the sauce, stir three minutes, or until thickened

.

Two all-time favorites, the dishes which constituted the “best meal [he’d] ever eaten ever,” were Mary’s chop suey and lime ice.

Chop Suey

Mary’s adventurous culinary style certainly resonated with the Chinese-American tradition of chop suey, the name of which translates from Cantonese as “miscellaneous odds and ends.” Her recipe includes chicken, shrimp, various vegetables, canned fried noodles, and even something that the Chinese in Cuba called

orejas

or “ears,” which Mary thought were either membranes of pig or monkey ears or some sort of vegetable. Most likely she was using a type of Chinese mushroom called “tree ears,” which are available in most Asian markets. She may even have added slices of mango to this dish on occasion

.

4

SERVINGS

For the Marinade

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon soy sauce

½ teaspoon sesame oil

2 tablespoons white wine

For the Chop Suey

½ pound chicken, cut into strips

4 tablespoons olive or sesame oil

½ pound shrimp, shelled and deveined

1 onion, chopped

¼ cup bamboo shoots

1 red bell pepper, sliced thin

1 scallion, chopped

½ cup sliced tree ears, or Chinese mushrooms

1 2-ounce can fried Chinese noodles

2 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1-inch piece ginger, minced

½ cup bean sprouts

1 mango, cubed (optional)

For the Gravy

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon cornstarch

2 teaspoons soy sauce

¼ cup water

Whisk together all the marinade ingredients in a large bowl. Add the chicken, cover, and let stand for at least 10 minutes.

Heat half the olive or sesame oil in a large skillet over high heat. When hot, add the chicken and stir-fry for 1-2 minutes. Add the shrimp and stir-fry until the shrimp turns bright pink. Remove the chicken and shrimp from the skillet and set aside. Return the skillet to high heat and add the remaining 2 tablespoons oil. Add the vegetables, mushrooms, fried noodles, garlic, and ginger and stir-fry for 2-3 minutes. Whisk together the gravy ingredients in a small bowl. Return the chicken and shrimp to the skillet. Toss together along with the sprouts and the mango. Pour in the gravy and cook for another 2-3 minutes. Serve immediately. Mary recommends that this dish be eaten with chopsticks, which she found helped the flavor.

Lime Ice

This dessert, clean and tart with just enough kick, is the perfect refreshment on a hot July afternoon in the hills just outside of Havana

.

4

TO

6

SERVINGS

1½ cups sugar syrup (see below)

Juice of 6 limes

½ tablespoon lemon juice

1 cup water

1 egg white

3½ tablespoons gin

2 tablespoons creme de menthe

Rind of ½ lime, very finely chopped (optional)

To make the sugar syrup, dissolve 1¼ cups sugar in 1 cup water. This may be done by stirring the sugar into the water either at room temperature or over low heat. If done over heat, allow the syrup to cool completely before proceeding.

Remove the rind of half of 1 lime and cover with plastic wrap. Combine the juice of the 6 limes, lemon juice, sugar syrup, water, and egg white in a large-bottomed, sturdy plastic container, so that the liquid is no more than 2 inches deep. Stir the mixture completely. Cover and place in the freezer for 1½–2 hours. When ice has formed around the edge of the mixture and the center is slushy, blend for a few seconds with a hand mixer or whisk. Cover and return to the freezer for another 1½

hours or so. Repeat process, adding the gin, creme de menthe, and minced lime rind after the third freezing.

Return the mixture to the freezer for another 30-60 minutes, or until firmly frozen. The ice may be served directly from the freezer, as it will stay somewhat soft and scoopable with the alcohol included.

Mary had access to a dozen different varieties of mangoes in Cuba, and she and Ernest enjoyed every type. Mary added mango slices to virtually every dish, whether it was Chinese, Mexican, or Italian. She froze mangoes in batches separated by flavor, which ranged from strawberry to honeydew, and served them with game or as dessert. She also made preserves and chutney to ensure there would be mango every day of the year. Mango chutney is a fresh alternative to regular salsas or chutneys and is easily prepared any time ripe mangoes are available.

Mango Chutney

8

TO

10

SERVINGS

2 large underripe mangoes, diced (see below)

¾ cup white vinegar

½ cup brown sugar

1 medium onion, chopped fine

1 clove garlic, finely minced

½ cup raisins

½ cup chopped crystallized ginger

½ teaspoon ground cloves

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cumin

½ cup hot water

½ teaspoon curry powder

1 tablespoon olive oil

Dash of black pepper

Mangoes have a large, flat pit. The easiest way to dice the flesh of a mango is to cut the fruit in half, working the knife flush against the flat side of the pit. Then repeat on the other side to cut away the other half. With a bread knife, cut a grid into the flesh, not cutting through the skin of the mango. Then push from the skin side and invert each half from concave to convex. You can then simply cut away the already cubed flesh.

Place the cubed mango in a medium saucepan. Add the remaining ingredients and mix together. Place the saucepan over medium heat and bring to a boil.

Lower the heat and simmer for 30-45 minutes, or until thickened. You may need to add more hot water if the chutney is too thick at this point. Allow to cool to room temperature before serving.

While Mary enjoyed cooking a vast variety of international dishes, she also embraced the cuisine of Cuba. One of her favorite hot-weather dishes was

picadillo

a classic Cuban dish. This recipe is based on Mary’s and includes the ubiquitous mango, which adds an extra splash of sweetness. The directions for this dish are Mary’s own and come from an article that she wrote for

Flair

magazine in 1951 entitled “Life with Papa.”

Picadillo

4

SERVINGS

2 medium onions, finely sliced

3 cloves garlic, finely chopped

3 tablespoons butter

1 pound ground beef

Salt

Pepper

Big dash of marjoram

Big dash of oregano

½ cup dry white wine

½ cup raisins

1 cup mango or peach, fairly finely chopped

½ cup sliced celery

¼ cup sliced stuffed olives

¼ cup chopped almonds, (optional)

Slice fine and fry in plenty of butter a medium-sized onion, or more if your family is big and you are using more than a pound of beef, also shredded garlic according to your taste. Stir in the meat with salt, pepper, a big dash of marjoram and a big dash of oregano, and before the meat starts burning or sticking to the pan, add about one-half cup of dry white wine. (Here the Cubans use, instead, tomato paste and water, but I prefer this dish without tomatoes.) Let this simmer gently for a while during which you make a platter of fluffy white rice. About five minutes before serving, add to the frying-pan mixture a half cup of previously soaked raisins, a cup of fairly finely chopped mango or fresh peach, half a cup of sliced celery, a handful of sliced stuffed olives and, if you wish to be fancy, a handful of blanched, chopped almonds [blanching briefly in boiling water is only necessary if the almonds still have their skin]. Pour the frying-pan mixture on top of the rice. Very small rivulets of the juice of the meat mixture should appear around the edges of the platter, or you haven’t used enough butter, wine or fruit. Garnish it with something dark green and very crisp.

Another dessert that was an all-time favorite of Mary and Ernest’s was coconut ice cream, which she prepared and served within the half-shells of real coconuts.

Coconut Ice Cream

1¼

QUARTS ICE CREAM

2½

cups heavy cream

1½

cups coconut milk

1 vanilla bean

8 egg yolks

¾ cup sugar

In a heavy saucepan, combine the cream and coconut milk. Cut the vanilla bean in half lengthwise. Scrape the seeds into the cream mixture and add the bean. Bring the cream mixture to a boil over medium heat and set aside.

In a mixing bowl, whisk together the egg yolks and sugar. When the cream mixture has cooled slightly, whisk about 1 cup into the egg yolks and sugar. Add this mixture to the remaining cream mixture in the saucepan. Return the saucepan to medium heat, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon. Heat for 3-5 minutes, or until the custard reaches 175° F and coats the back of the spoon. Remove from the heat. Pour the custard into a bowl and set over a larger bowl half-filled with ice water. Cool the custard for 10 minutes, stirring often.

Cover the custard with plastic wrap, allowing the plastic to settle on the surface. Refrigerate for 2 hours. Remove the vanilla bean, transfer the custard to an ice cream maker, and freeze according to manufacturer’s instructions. When finished, scoop the ice cream into halfshells of coconut, split open with a chisel and hammer.

6

EAST AFRICA AND IDAHO

A Hunter’s Culinary Sketches

In my nocturnal dreams, I am always between 25 and 30 years old, I am irresistible to women, dogs and, on one recent occasion, to a very beautiful lioness. . . . One of the aspects of this dream that I remember was that the lioness was killing game for me exactly as she would for a male of her own species; but instead of our having to devour the meat raw, she cooked it in a most appetizing manner. She used only butter for basting the impala chops. She braised the tenderloin and served it, on the grass, in a manner worthy of the Ritz in Paris. She asked me if I wanted any vegetables, and knowing that she herself was completely nonherbivorious, I refused in order to be polite. In any case, there were no vegetables.

—From “The Christmas Gift”

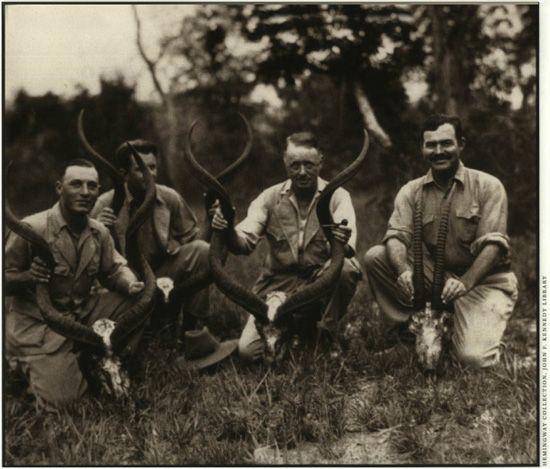

At the Kujungu Camp, Tanganyika, February 1934.

(Left to right) Ben Fourie, Charles Thompson, Philip Percival, and Hemingway displaying the bounty of a hunt.

Hemingway’s father, with his deep-set eyes and sharp, clear vision, was an excellent shot and avid hunter. As young Ernest grew older in a house increasingly dominated by women, Dr. Hemingway was eager to teach his young son the ways of the wild. Ernests older sister Marcelline was also included in Ed Hemingway’s regimented training but as Ernest himself would do later in life, Ed used these shared experiences to express his love for his son in particular.

By age five, Ernest had already begun to develop a love of fishing and hunting that would last his entire life. It was not until his teens, though, that his father would graduate him from his air rifle to target practice with a .22. Ed imparted discipline and respect for the weapons to his children and shared his contempt for hunters who killed for folly. The latter point, you may recall, resulted in the unfortunate porcupine incident of 1913 with Ernest and Harold Sampson.

These early experiences brought Ernest close to his father, even if they would later grow apart in many other ways. Years later he would thank his father, in a not wholly complimentary way through the semifictional voice of Nick Adams in the short story “Fathers and Sons”: