The Hemingway Cookbook (29 page)

Read The Hemingway Cookbook Online

Authors: Craig Boreth

Sherry

Sherry, a wine fortified with grape brandy from the Jerez region, is the most famous wine of Spain. The Spaniards’ passion for sherry eclipses that of the Portuguese for port. When Jake Barnes, Bill Gorton, and Robert Cohn sit beside the Plaza del Castillo as the Fiesta de San Fermín begins its week-long burn, it is no wonder that Hemingway bestows upon them this most Spanish of aperitifs:

The café was like a battleship stripped for action. To-day the waiters did not leave you alone all morning to read without asking if you wanted to order something. A waiter came up as soon as I sat down.

“What are you drinking?” I asked Bill and Robert.

“Sherry,” Cohn said.

“Jerez,” I said to the waiter.

27

In

A Moveable Feast

, Hemingway recalled drinking dry sherry with James Joyce despite Joyce’s reputation for drinking exclusively Swiss white wine.

28

MANZANILLA

Manzanilla is the palest of the Fino sherries, an extremely light, tart wine. It is the most popular accompaniment to tapas, the exquisite appetizers served in bars throughout Spain. When David and Catherine visit Madrid and the Prado in

The Garden of Eden

, they drink this “light and nutty tasting”

29

wine with their tapas: thin slices of jamón serrano, bright red and spicy sausages, anchovies, and garlic olives.

Sion

Sion is a Swiss white wine from the province of Valais. This is the suggested accompaniment, along with Aigle, to

Trout au Bleu

, page

58

. Both wines come from vineyards at the foot of the Bernese Alps.

Do you remember how Mrs. Gangeswisch cooked the trout au bleu when we got back to the chalet? They were such wonderful trout, Tatie, and we drank the Sion wine and ate out on the porch with the mountainside dropping off below and we could look across the lake and see the Dent du Midi with the snow half down it and the trees at the mouth of the Rhône where it flowed into the lake.

30

St. Estephe

Along with Capri, Frederic and Catherine drink this fruity, full Bordeaux red with their exquisite “last supper” together at the hotel in Milan.

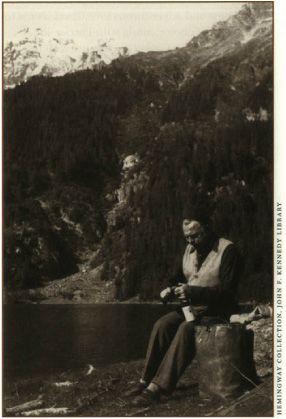

Hemingway opens a bottle of wine to enjoy in the majesty of the Swiss Alps.

Tavel

Norberto Fuentes, in his book

Hemingway in Cuba

, wrote that Tavel was Ernest’s favorite French rosé.

31

Tavel is sturdy and full bodied for a rosé and should be drunk in “its first blush of youth.”

32

In

The Garden of Eden

, a novel of the peril of new and adventurous love, Tavel seems to be the wine of choice, along with Perrier-Jouët Champagne. After Catherine returns with her hair cropped short, like a boy’s, she orders Tavel with lunch. “It is a great wine for people that [sic] are in love,”

33

she says. Later, David and Marita have Tavel with the artichoke hearts dipped in mustard sauce.

34

Valdepeñas

Before the recent ascension of wines from Rioja to the ranks of great celebrity, Valdepeñas was the best-known nonfortified Spanish wine. Throughout Hemingway’s days in Madrid, this was the favorite wine in the cafés. Smooth, ruby red, and well balanced, this valiantly alcoholic wine was no doubt enjoyed by Hemingway at Casa Botín in Madrid, along with Rioja Alta, over roast suckling pig. In

The Garden of Eden

, David and Catherine drink pitchers of Valdepeñas with their gazpacho:

They drank Valdepeñas now from a big pitcher and it started to build with the foundation of the marismeño only held back temporarily by the dilution of the gazpacho which it moved in on confidently. It built solidly.

“What is this wine?” Catherine asked.

“It’s an African wine,” David said.

“They always say that Africa begins at the Pyrenees,” Catherine said. “I remember how impressed I was when I first heard it.”

35

Valpolicella

Colonel Richard Cantwell enjoys this red wine, from the Veneto region in northeast Italy, at the Gritti Palace Hotel in Venice. He knows what he wants: “the light, dry, red wine which was as friendly as the house of your brother, if you and your brother are good friends.”

36

Cantwell also knows that Valpolicella is best if consumed within two years: “I believe that the Valpolicella is better when it is newer. It is not a grand vin and bottling it and putting years on it only adds sediment.”

37

Ostensibly because of this sediment, but more likely to save money, Cantwell persists in demanding that the wine be decanted from twolitre fiascos rather than from the bottle:

“He has your Valpolicella in the big wicker fiascos of two litres and I have brought this decanter with it.”

“That one,” the Colonel said. “I wish to Christ I could give him a regiment.”

38

8

THE HEMINGWAY BAR

“I have drunk since I was fifteen and few things have given me more pleasure. When you work hard all day with your head and know you must work again the next day what else can change your ideas and make them run on a different plane like whiskey? When you are cold and wet what else can warm you? Before an attack who can say anything that gives you the momentary well being that rum does?”

—Letter to Russian critic Ivan Kashkin

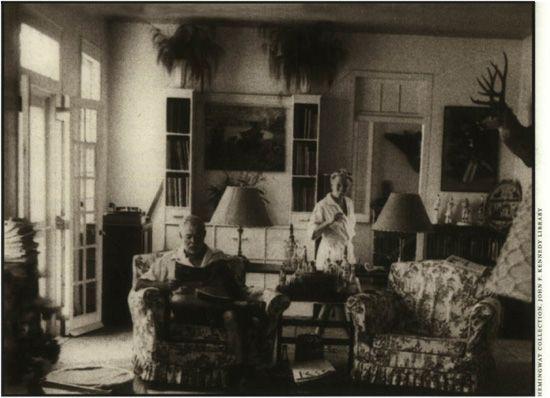

Hemingway and Mary by his table-bar at the Finca Vigía, the house on their fifteen-acre estate in Cuba.

Hemingway drank. A lot. For most of his life. The statement to Ivan Kashkin can be read in different ways, depending on the role (or roles) the reader believes alcohol played in Hemingway’s life. That he was an alcoholic is indisputable. The source of that alcoholism, while ultimately unimportant, remains a source of debate. Hemingway never openly admitted that he had a problem, yet he was quick to publicly point it out in others such as Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner.

Alcohol served him well in his early years. He spoke enthusiastically of its idea-changing properties and actively embraced the culture of alcohol while living in Paris. In an August 1922 dispatch to the

Toronto Star

weekly young Hemingway captured the hedonistic lure of early-evening Paris in a discourse on apéritifs:

Apéritifs, or appetizers, are those tall, bright red or yellow drinks that are poured from two or three bottles by hurried waiters during the hour before lunch and the hour before dinner, when all Paris gathers at the cafés to poison themselves into a cheerful pre-eating glow.

1

Later in his life, alcohol became the “giant killer,” helping him fight off his anxieties and bouts with severe depression. He needed it to get to sleep and to wake up. Eventually, as with Fitzgerald and Faulkner, it eroded his talent and certainly contributed to his death.

Why, then, has Hemingway remained the consummate “drinking writer,” inspiring a carefree indulgence for countless fans and readers? Because, for much of his life, he truly enjoyed drinking, and it did help him to maintain his craft. The eventual devastation notwithstanding, the image of the smiling, boisterous Hemingway, drink in hand and surrounded by friends, is one of the lasting images he left behind. If we live in the moment, get caught up in his generosity, and succumb to the charge he bestowed on a room upon entering, we may with honor and respect raise a glass to Ernest Hemingway and toast the good times.

To do so, we must familiarize ourselves with the Hemingway bar. Ernest was fastidious in his habit, indulging in his drinks of choice with the same dedication to detail that he had for his writing. While that may help us to understand why he wrote so much about drinking and drinkers, it in no way detracts from the magic he created when doing so. This may hint at another reason why the deleterious effects of drinking are often overlooked in Hemingway’s case: he made it sound like so damned much fun.

Absinthe

It took the place of the evening papers, of all the old evenings in cafés, of all chestnut trees that would be in bloom now in this month, of the great slow horses of the outer boulevards, of book shops, of kiosques, and of galleries, of the Pare Montsouris, of the Stade Buffalo, and of the Butte Chaumont, of the Guaranty Trust Company and the He de la Cité, of Foyot’s old hotel, and of being able to read and relax in the evening; of all the things he had enjoyed and forgotten and that came back to him when he tasted that opaque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy.

2

It’s a very strange thing,” he said. “This drink tastes exactly like remorse. It has the true taste of it and yet it takes it away.”

3

Absinthe is an emerald-green, very bitter liquor infused with herbs, primarily anise and wormwood. First distilled in the mountains of Switzerland, absinthe was later brought to fabulous popularity by the Frenchman Henri-Louis Pernod. Originally considered a stimulant to creativity, it was later believed that prolonged use of wormwood was harmful to the nervous system, producing a syndrome know as absinthism. Absinthe was banned throughout most Western countries between 1912 and 1915, although Spain continued to allow its use for some time thereafter.

Hemingway first discovered absinthe on his initial trips to Spain and the bullfights in the early 1920s. Absinthe was banned in France before he arrived, or else he would certainly have discovered it much earlier. Despite the ban, Hemingway continued to drink absinthe (and Pernod, the brand name of the imitation absinthe, produced without wormwood) well into the 1930s. In

Death in the Afternoon

, he explained, with tongue firmly in cheek, why he has decided to give up bullfighting (an endeavor that, in fact, he had never begun): “… it became increasingly harder as I grew older to enter the ring happily except after drinking three or four absinthes which, while they inflamed my courage, slightly distorted my reflexes.”

4

In 1935, Hemingway submitted an absinthe recipe of his own invention to a collection of celebrity cocktails, naming the drink after his famous book about bullfighting. Hemingway suggests slowly drinking three to five of these. If you're a nineteen-year-old bullfighter, maybe. Otherwise, I'd recommend against it.

Death in the Afternoon

1

SERVING

2½ ounces absinthe

Champagne, chilled

Pour absinthe into a Champagne flute. Top with Champagne.

While absinthe is now legal in the United States, that same mystique surrounding it expressed by Robert Jordan in For Whom the Bell Tolls remains: “It’s supposed to rot your brain out but I don't believe it. It only changes the ideas.”

5

For those not willing to risk the brain-rot, you may indulge in other anise-flavored spirits without wormwood, such as Pernod or Ricard. Of course, if you do so you will likely end up waiting in vain for “the feeling that makes [you] want to shimmy rapidly up the side of the Eiffel Tower.”

6