The Hidden Oasis (2 page)

Authors: Paul Sussman

Dr Jon Taylor, Curator of Cuneiform Collections at the British Museum, and Dr Frances Reynolds of Oxford University’s Faculty of Oriental Studies were kind enough to give me a steer on aspects of ancient Sumerian language; my good friends Dr Rasha Abdullah and Mohsen Kemal did the same for contemporary Egyptian Arabic.

Until recently I knew nothing whatsoever about rock climbing or flying aeroplanes and microlights. Thanks to the following I am now marginally less ignorant: Ken Yager of the Yosemite Climbing Association, Chris McNamara of SuperTopo, Paul Beaver, Captains Iain Gibson and Alex Keith, Lucy Kimbell of the Northamptonshire School of Flying and Roger Patrick of P & M Aviation. I was equally in the dark about the world of nuclear smuggling and uranium enrichment. The following gave generously of their time and expertise to help enlighten me: Professor Matthew Bunn of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, Gregory S. Jones of RAND Corporation, Brent M. Eastman of the US State Department’s Nuclear Smuggling Outreach Initiative, Ben Timberlake and Charlie Smith.

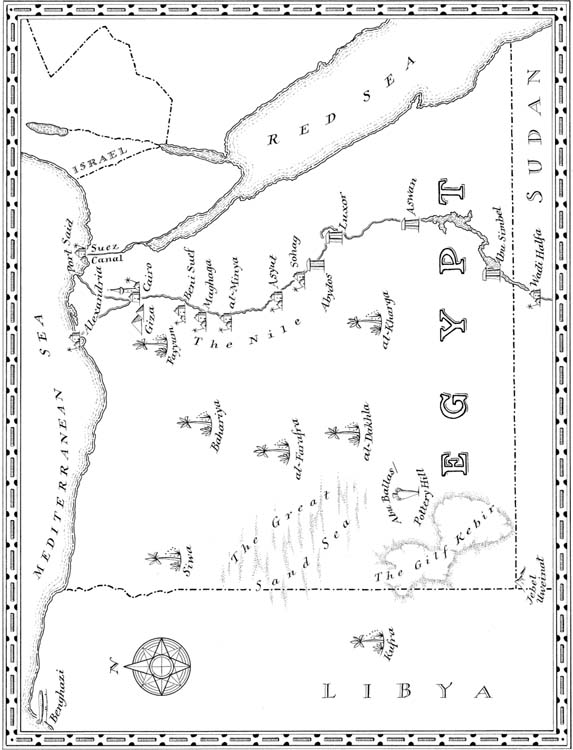

A huge thank you to John Berry for welcoming me at the US Embassy in Cairo, Neil Gower for his wonderful maps, Lieutenant-Colonel Brian Maka at the Pentagon, Nashwa at London’s Egyptian Cultural Bureau, Stephen Bagnold, Suzie Flowers, Dr Saul Kelly, Ken

Walton, Peter Wirth and staff at the British Library.

Perhaps the greatest pleasure of writing this book has been the opportunity it has given me to get to know two very special groups of people.

Thanks to Suzy Greiss, Magda Tharwat Badea and the staff of the Association for the Protection of the Environment (APE), I was able to enter and explore the fascinating world of the Zabbaleen, a unique community who for many years have collected and recycled Cairo’s rubbish. You can find out more about them and APE’s tireless outreach work at www.ape.org.eg. Sylvia Smith and Richard Duebel supplied me with crucial background information and introductions, and I am greatly indebted to them as well.

Equally unforgettable was the time I spent with the Bedouin of Dakhla Oasis.

Shukran awi

to Youssef, Sayed and El Hag Abdel Hamid Zeydan and Nasser Halel Zayed – for their hospitality, their insights and for many magical days out in the desert. If you ever find yourself in Dakhla, and want to learn more about the Bedouin and their culture, be sure to stop by the Zeydans’ Bedouin Camp (

http://www.dakhlabedouins.com

).

Last, but by no means least, I would like to mention two greatly valued friends – Peter Bowron and Paul Beard. Although not directly involved in the process of writing this book, they have been very much in my thoughts of late. Thanks for all the laughs, guys, and for making my life a richer, brighter, more enjoyable place. You will be sorely missed, and never forgotten.

BC

– E

GYPT, THE WESTERN DESERT

They had brought a butcher with them out into the far wastes of

deshret,

and it was a cattle-slaughtering knife rather than a ceremonial one that he used to cut their throats.

A savage implement of knapped yellow flint, razor-sharp and as long as a forearm, the butcher went from priest to priest expertly pressing its blade into the soft angle between neck and collarbone. Eyes glazed from the brew of

shepen

and

shedeh

they had drunk to dull the pain, their shaved heads glistening with droplets of sacred water, each man offered prayers to Ra-Atum, imploring Him to bring them safely through the Hall of Two Truths into the Blessed Fields of Iaru. Whereupon the butcher tilted their heads backwards towards the dawn sky and, with a single, firm sweep, slashed their necks from ear to ear.

‘May he walk in the beautiful ways, may he cross the heavenly firmament!’ the remaining priests chanted. ‘May he eat beside Osiris every day!’

Blood spattering across his arms and torso, the butcher

lowered each man to the ground and laid him flat before moving to the next priest in line and repeating the process, the row of bodies growing ever longer as he went about his business, blank-faced and brutally efficient.

From a nearby dune top Imti-Khentika, High Priest of Iunu, First Prophet of Ra-Atum, Greatest of Seers, gazed down at this choreographed slaughter. He felt sorrow, of course, at the deaths of so many men he had come to know as brothers. Satisfaction as well, though, for their mission was accomplished and every one of them had known from the outset that this was how it must end, so that no whisper should ever be spoken abroad of what they had done.

Behind him, in the east, he sensed the first warmth of the sun, Ra-Atum in His aspect as Khepri, bringing light and life to the world. He turned, throwing back his leopardskin hood and opening out his arms, reciting:

‘Oh Atum, who came into being on the hill of creation,

With a blaze like the Benu Bird in the Benben shrine at Iunu!’

He raised a hand, fingers spread as if to clasp the narrow rim of magenta peeping above the sands on the horizon. Then, turning again, he looked in the opposite direction, westwards, to the rearing wall of cliffs that ran north to south a hundred

khet

distant, like a vast curtain strung across the very edge of the world.

Somewhere at the base of those cliffs, in the thick mesh of shadows that the dawn light had yet to penetrate, was the Divine Gateway:

re-en wesir,

the Mouth of Osiris. It was invisible from where he was standing. And it would have been to an observer positioned right in front of it, for he,

Imti, had uttered the spells of closing and concealment and none but those who knew how to look would have been aware of the gateway’s presence. So it was that the place of their ancestors,

wehat er-djeru ta,

the oasis at the end of the world, had guarded its secrets across the endless expanse of years, its existence known only to a select few. Not for nothing was it also named

wehat seshtat –

the Hidden Oasis. Their cargo would be secure there. None would find it. It could rest in peace until more settled days should come.

Imti scanned the cliffs, his head nodding as if in approval, then he pulled his gaze back, to the warped spire of rock that burst from the dunes some eight

khet from

the cliff face. It was a striking feature even at this distance, dominating the surrounding landscape: a curving tower of black stone bowing outwards and upwards to a height of almost twenty

meh-nswt,

like some vast sickle blade ripping through the desert surface or, more appropriately, the foreleg of some gigantic scarab beetle clawing its way up through the sands.

How many travellers, Imti wondered, had passed that lone sentinel without realizing its significance? Few if any, he thought, answering his own question, for these were the empty lands, the dead lands, the domain of Set, where none who valued their lives would ever dream of venturing. Only those who knew of the forgotten places would come this far out into the burning nothingness. Only here would their charge be truly safe, far from the reach of those who would misuse its terrible powers. Yes, thought Imti, despite the horrors of their journey the decision to bring it west had been the right one. Definitely the right one.

Four moons ago now that decision had been taken, by a secret council of the most powerful in the land: Queen

Neith; Prince Merenre; the

tjaty

Userkef; General Rehu; and he, Imti-Khentika, Greatest of Seers.

Only the

nisu

himself, Lord of the Two Lands Nefer-ka-re Pepi, had not been present, nor informed of the council’s decision. Once Pepi had been a mighty ruler, the equal of Khasekhemwy and Djoser and Khufu. Now in the ninety-third year of his reign, three times the span of a normal man’s life, his power and authority had waned. Across the land the nomarchs raised private armies and made war on each other. To the north and the south the Nine Bows harried the borders. For three of the last four years the inundation had not come and the crops had failed.

Kemet

was disintegrating, and the expectation was that things would only get worse. Son of Ra Pepi might have been, but now, at this time of crisis, others must assume control and make the great choices of state for him. And so their council had spoken: for its own protection, and for the safety of all men, the

iner-en sedjet

must be taken from Iunu where it was housed and transported back across the fields of sand to the safety of the Hidden Oasis, whence it had originally come.

And to he, Imti-Khentika, High Priest of Iunu, had fallen the responsibility of leading that expedition.

‘Carry him across the winding waterway, ferry him to the eastern side of heaven!’

A renewed swell of chanting rose from below as another throat was cut, another body lowered to the ground. Fifteen lay there now, half their number.

‘Oh Ra, let him come to you!’ called Imti, joining in the chorus. ‘Lead him upon the sacred roads, make him live for ever!’

He watched as the butcher moved to the next man in line, the air echoing with the moist whistle of severed windpipes. Then, as the knife sliced again, Imti turned his eyes away across the desert, recalling the nightmare of the journey they had just undertaken.

Eighty of them had set out, at the start of the

peret

season when the heat was at its least fierce. With their cargo swathed in layers of protective linen and lashed to a wooden sled, they had travelled south, first by boat to Zawty, then overland to the oasis of Kenem. Here they had rested a week before embarking on the last and most daunting stage of their mission – forty

iteru

across the burning, trackless wastes of

deshret to

the great cliffs and the Hidden Oasis.

Seven long weeks that final leg had taken them, the worst Imti had ever known, beyond even his most terrible imaginings. Before they had even reached halfway their pack oxen were all dead and they had had to take up the load themselves, twenty of them at a time yoked together like cattle, their shoulders streaked with blood from the bite of the sled’s tow-ropes, their feet scorched by the fiery sands. Each day their progress had grown slower, hampered by mountainous dunes and blinding sandstorms, and above all by the heat, which even in that supposedly cool season had seared them from dawn until dusk as though the air itself was on fire.

Thirst, sickness and exhaustion had inexorably reduced their numbers and when their water had run out with still no sign of their destination he had feared their mission was doomed. Still they had trudged on, silent, indomitable, each lost in his private world of torment until on the fortieth day out of Kenem, the gods had rewarded their perseverance

with the sight for which they had so long been praying: a hazy band of red across the western horizon marking the line of the great cliffs and the end of their journey.

Even then it was a further three days before they reached the Mouth of Osiris and passed through it into the tree-filled gorge of the oasis, by which point there were only thirty of them still standing. Their burden had been consigned to the temple at the heart of the oasis; they had bathed in the sacred springs; and then, early this morning, the spells of closing and concealment recited, the Two Curses laid, they had trooped back out into the desert and the throat-cutting had begun.

A loud clatter snapped Imti from his reverie. The butcher, a mute, was banging the handle of his knife against a rock to attract his attention.

Twenty-eight bodies lay on the sand beside him, leaving just the two of them still alive. It was the end.

‘

Dua-i-nak netjer seni-i

,’ said Imti, descending the dune and laying a hand on the butcher’s blood-drenched shoulder. ‘Thank you, my brother.’

A pause, then:

‘You will drink

shepen?’

The butcher shook his head and handed over his knife, tapping two fingers against his neck to indicate where Imti should cut before turning and kneeling in front of him. The blade was heavier than Imti had imagined, less easy to control, and it took all his strength to lift it to the butcher’s throat and drag it across the flesh. He sliced as deep as he could, an explosion of frothy blood arching outwards across the sand.