The Hidden Oasis (5 page)

Authors: Paul Sussman

‘What the—’

His head was forced back further as a knee pressed into the base of his spine, huge hands clasping vice-like around his forehead and temples.

‘Mr Girgis invites you to dine with him.’

Other hands clawed at his mouth, prising apart his jaws, yanking them open, the bag coming closer to his face so that the ball-bearings dribbled directly down into his mouth, choking him. He bucked and writhed, his screams no more than a muted gurgle, but the hands held him tight and the pouring continued, on and on until the bag was empty and his jerking had grown weaker and eventually stopped altogether. They dropped his body on the floor, steel

trickling from between his bloodied lips, put a bullet through his head just to be certain and, without even glancing at the girl hunched against the wall, left. They were already speeding away into the dawn traffic when the hotel suddenly echoed to the crazed soprano of her screaming.

HE WESTERN DESERT, BETWEEN THE

G

ILF

K

EBIR AND

D

AKHLA

O

ASIS – THE PRESENT

They were the last Bedouin still making the great journey between Kufra and Dakhla, a 1,400-kilometre round trip through the empty desert. Using only camels for transport, they carried palm oil, embroideries, and silver and leather-work on the way out, and returned with dates, dried mulberries, cigarettes and Coca-Cola.

It made no economic sense, such a journey, but then it was not about economics. Rather, it was about tradition, keeping alive the old ways, following the ancient caravan routes that their fathers had followed, and their fathers before them, and their fathers before them, suviving where no one else could survive, navigating where no one else could navigate. They were tough people, proud, Kufra Bedouin, Sanusi, descendants of the Banu Sulaim. The desert was their home, travelling through it their life. Even if it did make no economic sense.

This particular trip had been hard even by the harsh standards of the Sahara, where no journey is ever easy. From Kufra, the trek south-east to the Gilf Kebir and through the

al-Aqaba gap – the direct route east would have taken them into the Great Sand Sea which even the Bedouin dared not cross – had passed off uneventfully.

Then, at the eastern end of the gap, they had discovered that the artesian well at which they would normally have filled their water-skins had dried up, leaving supplies dangerously tight for the remaining three hundred kilometres. It was a concern, but not a disaster, and they had continued north-east to Dakhla without any great sense of alarm. Two days on, however, and still three from their destination, they had been hit by a ferocious sandstorm, the feared

khamsin.

Forced to hunker down for 48 hours until it blew over, their water supplies had in the process dwindled to next to nothing.

Now the storm was gone and they were on the move again, pushing hard to cover the remaining distance before their water ran out completely, their camels lolloping across the desert just short of a full trot, driven on by cries of

‘hut, hut!’

and

‘yalla, yalla!’

So intent were the Bedouin on reaching their journey’s end as swiftly as possible that they would almost certainly have missed the corpse had it not appeared directly in their path. Rigid as a statue, it protruded waist up from the side of a dune, mouth open, one arm extended as though imploring them for help. The lead rider shouted, they slowed to a halt and, bringing their camels down onto the sand and dismounting, gathered around to look, seven of them,

shaals

wrapped around their heads and faces against the sun so that only their eyes were visible.

It was the body of a man, no doubt about that, perfectly preserved in the desert’s desiccating embrace, the skin

dried and tightened to the consistency of parchment, the eyes shrivelled in their sockets to hard, raisin-like nuggets.

‘The storm must have uncovered it,’ said one of the riders, speaking

badawi,

Bedouin Arabic, his voice coarse and gravelly, like the desert itself.

At a signal from their leader three of the Bedouin dropped to their knees and started to scoop sand away from the corpse, freeing it from the dune. Its clothes – boots, trousers, long-sleeved shirt – were worn ragged, as if they had undergone an arduous journey. A plastic thermos flask was still clutched in one of its hands, empty, the screw-top gone, the rim scarred with what looked like teeth marks, as though in his desperation the man had chewed at the plastic, hopelessly biting for whatever tiny drop of moisture remained within.

‘Soldier?’ asked one of the Bedouin doubtfully. ‘From the war?’

The leader shook his head, squatting down and tapping the scratched Rolex Explorer watch around the body’s left wrist.

‘More recent,’ he said.

‘Amrekanee.

American.’

He used the word not specifically, but to denote anyone of western, non-Arab appearance.

‘What’s he doing out here?’ asked another of the men.

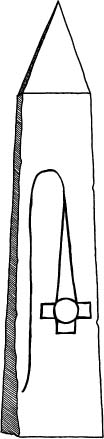

The leader shrugged and, rolling the body onto its front, tugged a canvas bag off its shoulder and opened it, removing a map, a wallet, a camera, two distress flares, some emergency rations and, finally, a balled-up handkerchief. He unfolded this, revealing a miniature clay obelisk, crudely made and no longer than his finger. He squinted at it, turning it this way and that, examining the curious

symbol with which each of its four faces was incised: a sort of cross, its top arm tapering to a point from which a thin looping line curled upwards and over like a tail. It meant nothing to him and, balling it in the handkerchief again, he laid it aside and turned his attention to the wallet. There was an ID card inside, bearing a photo of a young, blond-haired man with a heavy scar running parallel to his bottom lip. None of the Bedouin could read the writing on the card and, after gazing at it a moment, the leader returned it and the other objects to the knapsack. He began patting the man’s pockets, and pulled out a compass and a plastic canister with a roll of used camera film inside. These too he dropped into the knapsack, before tugging the watch off the man’s wrist, slipping it into the pocket of his

djellaba

and coming to his feet.

‘Let’s get going,’ he said, swinging the knapsack onto his shoulder and heading back towards the camels.

‘Shouldn’t we bury him?’ one of the men called after him.

‘The desert’ll do it,’ came the reply. ‘We need to get on.’

They followed him down the dune and mounted their camels, kicking at them to bring them upright. As they moved off, the last rider – a small, wizened man with pockmarked skin – turned in his saddle and looked back, gazing at the body as it slowly receded behind them. Once it had faded to no more than a blurred lump on the otherwise featureless desert he fumbled within the folds of his

djellaba

and pulled out a mobile phone. Keeping one eye on the riders in front to ensure no one was looking round at him, he pressed at the keypad with a gnarled thumb. He couldn’t get a signal, and after trying for a couple of minutes gave up and returned the phone to his pocket.

‘Hut-hut!’

he cried, slapping his heels into his camel’s quivering flanks.

‘Yalla, yalla!’

ALIFORNIA

, Y

OSEMITE

N

ATIONAL

P

ARK

It was a five-hundred-metre wall of vertical rock rearing above the Merced Valley like a billow of grey satin, and Freya Hannen was just fifty metres from its summit when she disturbed the wasps’ nest.

She had toed into a small rock pocket near the top of her tenth pitch and, reaching up onto an overhanging ledge, was feeling for purchase around the roots of an

old manzanita bush when she accidentally swiped the nest, a cloud of insects erupting from beneath the bush and swarming angrily around her.

Wasps were her primal fear, had been since she had been stung in the mouth by one as a child. A ridiculous fear to have, given that she made her living climbing some of the world’s most dangerous rock faces, but then terror is rarely rational. For her sister Alex it was needles and injections; for Freya, wasps.

She froze, stomach tightening, her breath coming in short panicked gasps, the air around her a mesh of skimming yellow-jackets. Then one stung her on the arm. Unable to stop herself, she snatched her hand away from the ledge and barn-doored outwards from the rock, her lead-line flapping wildly, the ponderosa forest 450 metres below seeming to telescope up towards her. For a moment she swung, hinging on her right hand and foot, her left limbs flapping in space, carabiners and cams jangling on her harness. Then, gritting her teeth and trying to ignore the burning sensation on her arm, she heaved herself back to the wall and locked her hand around a protruding rock knuckle, pressing into the warm granite as though into a lover’s protective embrace. She remained like that for what felt like an age, eyes closed, fighting the urge to scream, waiting for the swarm to calm and dissipate, then traversed swiftly to her right beneath the ledge and climbed up further along, beside a stunted pine that lurched outwards from the rock like a withered arm. She anchored herself there and sat back against the trunk, panting.

‘Shit,’ she gasped. And then, for no obvious reason: ‘Alex.’

It was eleven hours since she had received the call. She had been back at her apartment in San Francisco when it had come, just after midnight, totally out of the blue, after all these years. Once, early in her climbing career, she had lost her footing and fallen from a two-hundred-metre rock face, plunging vertiginously through open space before her line caught and held her. That’s how the call had felt: an initial giddy sense of bewilderment and disbelief, like plummeting from a great height, followed by a sudden, sickening jerk of realization.

Afterwards she had sat in darkness, the late-night sounds of North Beach’s bars and cafés drifting in through the open windows. Then, going online, she had booked herself a flight before throwing some gear into a bag, locking up the apartment and roaring off on her battered Triumph Bonneville. Three hours later she was in Yosemite; two hours after that, with the first pink of dawn staining the heads of the Sierra Nevada, at the base of Liberty Cap, ready to start her ascent.

It was what she always did in times of turmoil, when she needed to clear her head – climbed. Deserts were Alex’s thing: vast, dry, empty spaces, devoid of life and sound; mountains and rock were Freya’s – rearing, vertical landscapes through which she could clamber up towards the sky, pushing mind and body to the limit. It was impossible to explain to those who had never experienced it; impossible to explain even to herself. The closest she had come was in an interview with, of all things,

Playboy

magazine: ‘When I’m up there I just feel more alive,’ she had said. ‘Like the rest of the time I’m half asleep.’

Now, more than ever, she needed the peace and clarity

that climbing brought her. Thundering east along Highway 120 towards Yosemite her first instinct had been to free-climb a route, something really tough, punishing: Freerider on El-Capitan, perhaps, or Astroman on Washington Column.

Then she had started thinking about Liberty Cap, and the more she had thought about it, the more attractive it had seemed.

It was not an obvious choice. Parts of it were aided, which necessitated extra equipment and denied her the absolute purity of a free-climb; technically it wasn’t actually that difficult, not by her standards, which meant that she would not be pushing herself as hard as she wanted: not right to the very edge and beyond.

Against that, it was one of the few Yosemite big walls she had never attempted before. More important, it was probably the only one that at this time of year was not going to be covered with a scrabble of other climbers, thereby ensuring absolute peace and solitude – no one talking to her, no one trying to take her photo, no amateurs blocking her way and slowing her down. Just her and the rock and the silence.

Sitting on the ledge now, the midday sun warming her face, her arm still smarting from the wasp sting, she took a gulp from the water bottle in her day-pack and gazed down at the route she’d just ascended. Apart from a couple of aided sections it hadn’t thrown up too many problems. A less experienced climber might have taken a couple of days to summit, overnighting on a ledge halfway up. She would do it in less than half that time. Eight hours tops.

She still couldn’t escape a vague twinge of disappointment that it hadn’t stretched her more, taken her to that heady, intoxicating plateau reached only through extreme

physical and mental exertion. Then again the views from up there were so spectacular, the sense of removedness so complete she could forgive the lack of challenge. Yes, she thought, in the circumstances Liberty Cap had been just what she needed. Holding on to the anchor rope she extended her legs – long, tanned, toned – rubbing at the muscles, pointing the tips of her Anasazi climb shoes to stretch out her feet and shins. Then, standing and turning, she scanned the rock above ready to start her eleventh and final pitch, fifty metres up to the summit.