The Hindus (116 page)

Authors: Wendy Doniger

MODERN AVATARS OF THE AVATARS

RADHA THE SOCIAL WORKER

RADHA THE SOCIAL WORKER

In 1914, a tax officer near Varanasi named Hariaudh published a long poem entitled “Sojourn of the Beloved” (

Priyapravas

), in which Radha rejects the sensuality of erotic longing for Krishna, undertakes a vow of virginity, and dedicates herself to the “true bhakti” of social service. Fusing elements of Western social utilitarianism, bits of Wordsworth and Tagore, and the monistic Vedanta of Vivekananda, Radha substitutes for each of the nine conventional types of bhakti a particular type of altruistic good works: The loving service she would have given to Krishna as his wife is now directed to the “real world”; the bhakti of being Krishna’s servant or slave becomes lifting up the low and fallen castes; remembering Krishna becomes remembering the troubles of poor, helpless widows and orphans, giving medicine to those in pain, and giving shelter and dignity to those who have fallen through their karma. Hariaudh sees Radha’s vow of virginity as a solution for the perceived problem of improving the status of Indian women without opening the door to the sexual freedom of “Westernized” women. His revisionist myth of Radha managed simultaneously to offend conservative Brahminical Hinduism and to insult the living religious practices of Hinduism.

75

Not surprisingly, it did not replace the earlier, earthier version of the story of Radha.

THE GOOD DEMON BALI AND THE EVIL DWARFPriyapravas

), in which Radha rejects the sensuality of erotic longing for Krishna, undertakes a vow of virginity, and dedicates herself to the “true bhakti” of social service. Fusing elements of Western social utilitarianism, bits of Wordsworth and Tagore, and the monistic Vedanta of Vivekananda, Radha substitutes for each of the nine conventional types of bhakti a particular type of altruistic good works: The loving service she would have given to Krishna as his wife is now directed to the “real world”; the bhakti of being Krishna’s servant or slave becomes lifting up the low and fallen castes; remembering Krishna becomes remembering the troubles of poor, helpless widows and orphans, giving medicine to those in pain, and giving shelter and dignity to those who have fallen through their karma. Hariaudh sees Radha’s vow of virginity as a solution for the perceived problem of improving the status of Indian women without opening the door to the sexual freedom of “Westernized” women. His revisionist myth of Radha managed simultaneously to offend conservative Brahminical Hinduism and to insult the living religious practices of Hinduism.

75

Not surprisingly, it did not replace the earlier, earthier version of the story of Radha.

In 1885, Jotiba Phule, who belonged to the low caste of gardeners (Malis), published a Marathi work with an English introduction, in which he radically reinterpreted Puranic mythology, seeing the various avatars of Vishnu as stages in the deception and conquest of India by the invading Aryans, and Vishnu’s antigod and ogre enemies as the heroes of the people.

76

Bali, in particular, the “good antigod” whom the dwarf Vishnu cheated out of his kingdom, was refigured as Bali Raja, the original king of Maharashtra, reigning over an ideal state of benevolent castelessness and prosperity, with Khandoba and other popular gods of the region as his officials.

76

Bali, in particular, the “good antigod” whom the dwarf Vishnu cheated out of his kingdom, was refigured as Bali Raja, the original king of Maharashtra, reigning over an ideal state of benevolent castelessness and prosperity, with Khandoba and other popular gods of the region as his officials.

To this day many Maharashtrian farmers look forward not to Ram Rajya (they regard Rama as a villain) but to the kingdom of Bali,

77

Bali Rajya: “Bali will rise again,” and he will recognize the cultivating classes as masters of their own land. Low castes in rural central Maharashtra identify so closely with Bali, a son of the soil, against the dwarf, the archetype of the devious Brahmin, that they regularly greet each other as “Bali.” Sometimes they burn the dwarf in effigy.

78

THE BUDDHA AND KALKI77

Bali Rajya: “Bali will rise again,” and he will recognize the cultivating classes as masters of their own land. Low castes in rural central Maharashtra identify so closely with Bali, a son of the soil, against the dwarf, the archetype of the devious Brahmin, that they regularly greet each other as “Bali.” Sometimes they burn the dwarf in effigy.

78

In 1990, Pakistani textbooks used a garbled version of the myth of the Buddha avatar to support anti-Hindu arguments: “The Hindus acknowledged Buddha as an avatar and began to worship his image. They distorted his teachings and absorbed Buddhism into Hinduism.” A Hindu critic then commented on this passage: “The message is oblique, yet effective—that Hinduism is the greatest curse in the subcontinent’s history and threatens to absorb every other faith.”

79

Vinay Lal’s delightful short book on Hinduism identifies President George W. Bush as the contemporary form of Kalki: He spends a lot of time with horses and is going to destroy the world.

80

THE TAJ MAHAL AND BABUR’S MOSQUE79

Vinay Lal’s delightful short book on Hinduism identifies President George W. Bush as the contemporary form of Kalki: He spends a lot of time with horses and is going to destroy the world.

80

One advocate of Hindutva has argued, on the basis of absolutely no evidence, that the Taj Mahal, in Agra, is not a Islamic mausoleum but an ancient Shiva temple, which Shah Jahan commandeered from the Maharaja of Jaipur; that the term “Taj Mahal” is not a Persian (from Arabic) phrase meaning “crown of palaces,” as linguists would maintain, but a corrupt form of the Sanskrit term “Tejo Mahalaya,” signifying a Shiva temple; and that persons connected with the repair and the maintenance of the Taj have seen the Shiva linga and “other idols” sealed in the thick walls and in chambers in a secret red stone story below the marble basement.

81

In 2007, the Taj was closed to visitors for a while because of Hindu-Muslim violence in Agra.

82

81

In 2007, the Taj was closed to visitors for a while because of Hindu-Muslim violence in Agra.

82

On a more hopeful note, Muslims for many years participated in the Ganesh Puja in Mumbai by swimming the idol out into the ocean at the end of the festival. There are still many instances of this sort of interreligious cooperation, as there have been since the tenth century CE.

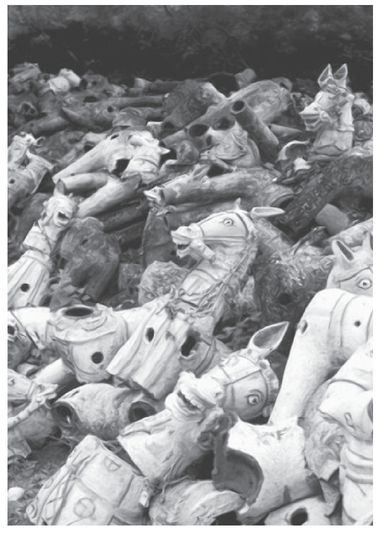

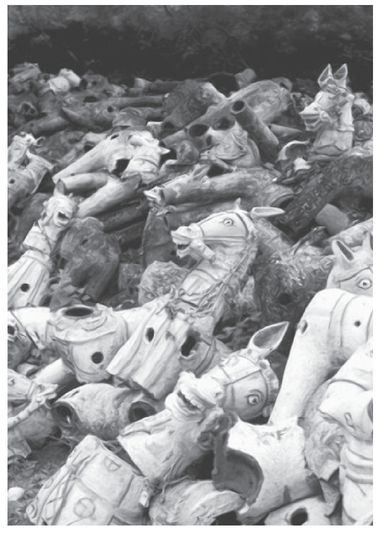

THE WORSHIP OF OTHER PEOPLE’S HORSESLet us consider the positive contribution of Arab and Turkish horses to contemporary Hindu religious life, particularly in villages. The symbol of the horse became embedded in the folk traditions of India and then stayed there even after its referent, the horse, had vanished from the scene, even after the foreigners had folded their tents and gone away. To this day, horses are worshiped all over India by people who do not have horses and seldom even see a horse, in places where the horse has never been truly a part of the land. In Orissa, terra-cotta horses are given to various gods and goddesses to protect the donor from inauspicious omens, to cure illness, or to guard the village.

83

In Bengal, clay horses are offered to all the village gods, male or female, fierce or benign, though particularly to the sun god, and Bengali parents until quite recently used to offer horses when a child first crawled steadily on its hands and feet like a horse.

84

83

In Bengal, clay horses are offered to all the village gods, male or female, fierce or benign, though particularly to the sun god, and Bengali parents until quite recently used to offer horses when a child first crawled steadily on its hands and feet like a horse.

84

In Tamil Nadu today, as many as five hundred large clay horses may be prepared in one sanctuary, most of them standing between fifteen and twenty-five feet tall (including a large base) and involving the use of several tons of stone, brick, and either clay, plaster, or cement.

85

They are a permanent part of the temple and may be renovated at ten- to twenty-year intervals; the construction of a massive figure usually takes between three to six months. (Many of them have the curved Marwari ears.) The villagers say that the horses are ridden by spirit riders who patrol the borders of the villages, a role that may echo both the role of the Vedic horse in pushing back the borders of the king’s realm and the horse’s association with aliens on the borders of Hindu society. But the villagers do not express any explicit awareness of the association of the horses with foreigners; they think of the horses as their own.

85

They are a permanent part of the temple and may be renovated at ten- to twenty-year intervals; the construction of a massive figure usually takes between three to six months. (Many of them have the curved Marwari ears.) The villagers say that the horses are ridden by spirit riders who patrol the borders of the villages, a role that may echo both the role of the Vedic horse in pushing back the borders of the king’s realm and the horse’s association with aliens on the borders of Hindu society. But the villagers do not express any explicit awareness of the association of the horses with foreigners; they think of the horses as their own.

A Marxist might view the survival of the mythology of the aristocratic horse as an imposition of the lies of the rulers upon the people, an exploitation of the masses by saddling them with a mythology that never was theirs nor will ever be for their benefit, a foreign mythology that produces a false consciousness, distorting the native conceptual system, compounding the felony of the invasion itself. A Freudian, on the other hand, might see in the native acceptance of this foreign mythology the process of projection or identification by which one overcomes a feeling of anger or resentment or impotence toward another person by assimilating that person into oneself,

becoming

the other. Myths about oppressive foreigners (and their horses) sometimes became a positive factor in the lives of those whom they conquered or dominated.

becoming

the other. Myths about oppressive foreigners (and their horses) sometimes became a positive factor in the lives of those whom they conquered or dominated.

When enormous terra-cotta horses are constructed in South India, the choice of medium is both practical (clay is cheap and available) and symbolic. New horses are constantly set up, while the old and broken ones are left to decay and return to the earth of which they were made.

86

Clay, as Stephen Inglis points out, is the right medium for the worship of a creature as ephemeral as a horse—“semi-mythical, temporary, fragile, cyclical (prematurely dying/transforming).”

87

Elsewhere Inglis has described the work of the Velar, the potter caste that makes the horses: “By virtue of being made, of earth, the image is bound to disintegrate and to be reconstituted. . . . The potency of the craft of the Velar lies in impermanence and potential for deterioration, replacement, and reactivization of their services to the divine. . . . The Velar, and many other craftsmen who work with the immediate and ever changing, are . . . specialists of impermanence.”

88

The impermanence of the clay horses may also reflect the awareness of the fragility of both horses in the Indian climate and the foreign dynasties that came and, inevitably, went, leaving the legacy of their horses.

MODERN WOMEN86

Clay, as Stephen Inglis points out, is the right medium for the worship of a creature as ephemeral as a horse—“semi-mythical, temporary, fragile, cyclical (prematurely dying/transforming).”

87

Elsewhere Inglis has described the work of the Velar, the potter caste that makes the horses: “By virtue of being made, of earth, the image is bound to disintegrate and to be reconstituted. . . . The potency of the craft of the Velar lies in impermanence and potential for deterioration, replacement, and reactivization of their services to the divine. . . . The Velar, and many other craftsmen who work with the immediate and ever changing, are . . . specialists of impermanence.”

88

The impermanence of the clay horses may also reflect the awareness of the fragility of both horses in the Indian climate and the foreign dynasties that came and, inevitably, went, leaving the legacy of their horses.

CASTE REFORM AND IMPERMANENCE: THE WOMEN PAINTERS OF MITHILA

The impermanence of the massive clay horses is one facet of a larger philosophy of impermanence in ritual Hindu art.

In many domestic rituals throughout India, women trace intricate designs in rice powder (called

kolams

in South India) on the immaculate floors and courtyards of houses, and after the ceremony these designs are blurred and smudged into oblivion by the bare feet of the family, or as the women think of it, the feet of the family carry into the house, from the threshold, the sacred material of the design. As David Shulman has written:

kolams

in South India) on the immaculate floors and courtyards of houses, and after the ceremony these designs are blurred and smudged into oblivion by the bare feet of the family, or as the women think of it, the feet of the family carry into the house, from the threshold, the sacred material of the design. As David Shulman has written:

The

kolam

is a sign; also both less and more than a sign. As the day progresses, it will be worn away by the many feet entering or leaving the house. The rice powder mingles with the dust of the street; the sign fails to retain its true form. Nor is it intended to do so, any more than are the great stone temples which look so much more stable and enduring: they too will be abandoned when the moment of their usefulness has passed; they are built not to last but to capture the momentary, unpredictable reality of the unseen.

89

kolam

is a sign; also both less and more than a sign. As the day progresses, it will be worn away by the many feet entering or leaving the house. The rice powder mingles with the dust of the street; the sign fails to retain its true form. Nor is it intended to do so, any more than are the great stone temples which look so much more stable and enduring: they too will be abandoned when the moment of their usefulness has passed; they are built not to last but to capture the momentary, unpredictable reality of the unseen.

89

The material traces of ritual art must vanish in order that the mental traces may remain intact forever. If the megalomaniac patrons of so many now ruined Hindu temples smugly assumed that great temples, great palaces, great art would endure forever, their confidence was not shared by the villagers who actually did the building.

A Herd of Laughing Clay Horses from a Rural Temple, Madurai District.

The smearing out of the

kolam

is a way of defacing order so that one has to re-create it. The women who make these rice powder designs sometimes explicitly refer to them as their equivalent of a Vedic sacrificial hall (

yajnashala

), which is also entirely demolished after the sacrifice. Their sketches are referred to as “writing,” often the only form of writing that for many centuries women were allowed to have, and the designs are merely an aide-mémoire for the patterns that they carry in their heads, as men carry the Vedas. So too, the visual abstraction of designs such as the

kolam

is the woman’s equivalent of the abstraction of the Vedic literature, based as it is on geometry and grammar. The rice powder designs are a woman’s way of abstracting religious meanings; they are a woman’s visual grammar.

90

kolam

is a way of defacing order so that one has to re-create it. The women who make these rice powder designs sometimes explicitly refer to them as their equivalent of a Vedic sacrificial hall (

yajnashala

), which is also entirely demolished after the sacrifice. Their sketches are referred to as “writing,” often the only form of writing that for many centuries women were allowed to have, and the designs are merely an aide-mémoire for the patterns that they carry in their heads, as men carry the Vedas. So too, the visual abstraction of designs such as the

kolam

is the woman’s equivalent of the abstraction of the Vedic literature, based as it is on geometry and grammar. The rice powder designs are a woman’s way of abstracting religious meanings; they are a woman’s visual grammar.

90

Since the fourteenth century, the women of the Mithila region of northern Bihar and southern Nepal have made wall and floor paintings on the occasion of marriages and other domestic rituals.

91

These paintings, inside their homes, on the internal and external walls of their compounds, and on the ground inside or around their homes, created sacred, protective, and auspicious spaces for their families and their rituals. They depicted Durga, Krishna, Shiva, Vishnu, Hanuman, and other Puranic deities, as well as Tantric themes, a headless Kali (or, sometimes, a many-headed Kali) trampling on Shiva, or Shiva and Parvati merged as the androgyne.

92

91

These paintings, inside their homes, on the internal and external walls of their compounds, and on the ground inside or around their homes, created sacred, protective, and auspicious spaces for their families and their rituals. They depicted Durga, Krishna, Shiva, Vishnu, Hanuman, and other Puranic deities, as well as Tantric themes, a headless Kali (or, sometimes, a many-headed Kali) trampling on Shiva, or Shiva and Parvati merged as the androgyne.

92

The women painters of Mithila used vivid natural dyes that soon faded, and they painted on paper, thin, frail paper. This impermanence did not matter to the artists, who did not intend the paintings to last. The

act

of painting was seen as more important than the form it took, and they threw away elaborately produced marriage sketches when the ceremony was over, leaving them to be eaten by mice or using them to light fires. Rain, whitewash, or the playing of children often destroyed frescoes on courtyard walls.

93

To some extent, this is a concept common to many artists, particularly postmodern artists, such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, whose temporary installations included

Running Fence,

a twenty-four-mile-long white nylon fabric curtain in Northern California. Such artists are interested in the act of creation, not in preserving the object that is created. But this ephemerality takes on a more particular power in the realm of sacred art, even more particularly in the sacred art of women, who, in contrast with the great granite monomaniac monuments of men, are primarily involved in producing human services that leave no permanent trace, with one great exception, of course: children.

act

of painting was seen as more important than the form it took, and they threw away elaborately produced marriage sketches when the ceremony was over, leaving them to be eaten by mice or using them to light fires. Rain, whitewash, or the playing of children often destroyed frescoes on courtyard walls.

93

To some extent, this is a concept common to many artists, particularly postmodern artists, such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, whose temporary installations included

Running Fence,

a twenty-four-mile-long white nylon fabric curtain in Northern California. Such artists are interested in the act of creation, not in preserving the object that is created. But this ephemerality takes on a more particular power in the realm of sacred art, even more particularly in the sacred art of women, who, in contrast with the great granite monomaniac monuments of men, are primarily involved in producing human services that leave no permanent trace, with one great exception, of course: children.

Other books

The Riddle (A James Acton Thriller, Book #11) by J. Robert Kennedy

Unknown by Unknown

Venus in Blue Jeans by Meg Benjamin

The Long Ride Home (Cowboys & Cowgirls) by Zwissler, Danielle Lee

The Dark Remains by Mark Anthony

Man Up Stepbrother by Danielle Sibarium

Thatcher by Clare Beckett

A Brief History of the Private Lives of the Roman Emperors by Anthony Blond

The Wall by Artso, Ramz