The House of Tudor (9 page)

Read The House of Tudor Online

Authors: Alison Plowden

Tags: #History, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Nonfiction, #Tudors, #15th Century, #16th Century

No one, least of all the Almighty’s anonymous scriptwriter, could have guessed how bitterly ironical his words would turn out to be.

The Spaniards, of course, were accustomed to religious shows and processions, but they had never seen anything quite on this scale before and they rode wide-eyed behind the scarlet-robed Lord Mayor and aldermen through a fairy-tale city, with the trumpets braying and the Tower cannon booming in their ears. ‘The princess’, exclaimed the Licentiate Alcares, ‘could not have been received with greater joy had she been the saviour of the world.’

The Londoners packing the streets and hanging out of every window along the route were regrettably inclined to laugh at the outlandish appearance of the foreigners, but for the princess herself there was nothing but praise. Catherine, in rich Spanish apparel, was riding a gorgeously trapped mule and wore ‘a little hat fashioned like a cardinal’s hat...with a lace of gold at this hat to stay it, her hair hanging down about her shoulders’. She must have made a charmingly exotic picture and young Thomas More, a law student at Lincoln’s Inn, declared enthusiastically ‘there is nothing wanting in her that the most beautiful girl should have’. The royal family, who were watching the show from a merchant’s house in Cheapside, had every reason to be pleased, and for the King and Queen there was the added satisfaction of seeing ten-year-old Prince Henry carrying out his first important public engagement with perfect aplomb, as he rode through the crowded streets at his new sister’s right hand.

The procession ended with a final pageant at the entrance to St. Paul’s Churchyard, and Catherine and her retinue were installed in the Bishop of London’s palace which adjoined the west door of the cathedral. Next day, the eve of the wedding, there was a state reception for the Spanish dignitaries in the great hall of Baynard’s Castle, the King sitting under a cloth of estate with his two sons on either side of him. In the afternoon the princess paid a ceremonial visit to the Queen and afterwards there was more dancing and merrymaking, so that it was quite late in the evening before she returned by torchlight to her lodging. ‘Thus’, remarks the chronicler, ‘with honour and mirth this Saturday was expired and done.’

Prince Arthur arrived at St. Paul’s between nine and ten o’clock on the morning of Sunday, 14 November escorted by the Earls of Oxford and Shrewsbury, and shortly afterwards the bride emerged from the bishop’s palace. She was met at the west door of the cathedral by the Archbishop of Canterbury, supported by eighteen other bishops and abbots mitred, and led down the six-hundred-foot length of the great church to the choir. Prince Henry giving her his right hand and Cecily of York bearing her train. Bride and groom were both dressed in white satin, Catherine’s gown being made very wide ‘with many pleats, much like unto men’s clothing’ and worn over a Spanish hooped farthingale, while a white silk veil bordered with pearls and precious stones covered her face.

After the marriage service conducted by the Archbishop, which lasted more than three hours, the newly-wedded pair went hand in hand towards the high altar, turning to the south and north so that ‘the present multitude of people might see and behold their persons’. Trumpets, shawns and sackbuts sounded, and a great shout went up inside the cathedral, ‘some crying King Henry, some in likewise crying Prince Arthur’. Outside, the bells crashed, the conduits ran with wine and the waiting crowds cheered themselves hoarse.

As soon as the long-drawn-out religious ceremonies were over, the wedding guests trooped across the churchyard to the bishop’s palace, where a feast of ‘the most delicate dainties and curious meats that might be purveyed and gotten within the whole realm of England’ was laid out for them.

That day of pageantry, piety, emotion and over-eating ended with the customary ceremonious bedding of bride and groom, the prince being conducted by his lords and gentlemen (few of them entirely sober by this time) to the bridal chamber ‘wherein the princess before his coming was reverently laid and disposed’. The marriage bed was blessed by the assembled bishops and at last the young couple was left alone. A quarter of a century later, the details of that public bedding were to be as publicly re-hashed - even Arthur’s boyish boast of the following morning was produced in evidence. He had called for a drink, remembered someone, saying he had been that night in Spain and found it thirsty work.

The celebrations lasted a full fortnight. On Monday, while the princess rested in her apartments, the Spanish visitors were entertained to dinner and supper by the King’s mother and her husband, Lord Derby. On Tuesday, the King and all the quality went in state to hear mass at St. Paul’s and on Wednesday a number of new Knights of the Bath were created. On Thursday the Court moved to Westminster, where a tiltyard had been set up on the open space in front of Westminster Hall for a grand tournament in honour of the wedding - the champions vying with one another over the magnificence of their turn-out. On Friday, there was a state banquet inside the Hall with the new Princess of Wales seated on the King’s right hand. There was more ‘disguising’: a castle set on wheels with ladies looking out of the windows and singing boys warbling on the turrets was drawn in by a team of prototype pantomime horses - four heraldic beasts painted gold and silver and each containing two men, ‘one in the forepart and another in the hindpart’. This wonder was followed by a ship in full sail and finally by a third pageant ‘in likeness of a great hill...in which were enclosed eight goodly knights with their banners spread and displayed, naming themselves the Knights of the Mount of Love’. When these set pieces had been exclaimed over and towed away, the musicians struck up for dancing. The younger members of the royal family took the floor and Prince Henry, energetically partnering his sister Margaret, ‘perceiving himself to be accumbered by his clothes’, threw off his gown and danced in his jacket, much to the amusement of his parents.

It was the end of November before the party began to break up. Catherine was to keep a permanent staff of about sixty Spanish attendants, but dignitaries such as the Count of Cabra, the Archbishops of Toledo and Santiago, and the Bishops of Malaga and Majorca had only come to see her safely married and now, surfeited with hospitality and laden with expensive presents, they were ready to leave for Southampton to face another sea crossing. When the moment of parting came, the little bride (she was not yet sixteen) shed some tears, and we have a glimpse of the King taking a rather woebegone princess into his library at Richmond and showing her ‘many goodly pleasant books’ in an attempt to cheer her up. The next few months were bound to be a difficult period of adjustment for the Spanish girl and, before the royal family returned to its normal routine, a decision had to be taken about her immediate future.

Arthur must go back to Ludlow where, as Prince of Wales, he represented his father on the Welsh Marches and where he was learning the business of government under the guidance of a small but carefully chosen band of advisers. The question which now arose was, should his wife go with him? Some people doubted whether, at barely fifteen, the prince was old enough or strong enough to undertake the duties of a husband. They also questioned the wisdom of exposing the newly arrived princess to the rigours of life on the north-west frontier, especially in the dead of winter. Surely it would be better to leave her at Court for a while, where the Queen could keep an eye on her and teach her something of English ways? This would certainly seem to have been the most humane and prudent course, but the King hesitated. Whether he was thinking about the expense of maintaining a separate establishment for his daughter-in-law, whether he was worried about possible difficulties with Spain if she was kept apart from her husband, or whether he simply felt that the two young people should be given a chance to get to know each other away from the distractions of the Court is nowhere recorded; but whatever considerations influenced his decision, when Arthur left for Shropshire in December, Catherine and her Spanish household went too.

1 Margaret Beaufort as a young girl; an unauthenticated portrait by an unknown artist.

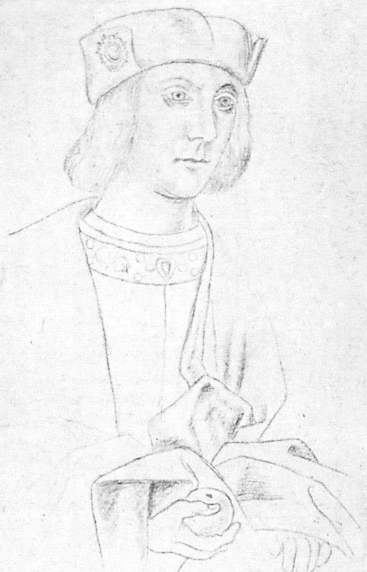

2 The young Henry Tudor; from the

Recueil d’Arras

.

3 Pembroke Castle, birthplace of Henry Tudor.

12 Henry, Duke of York, second son of Henry VII and his eventual successor.

13 Arthur, Prince of Wales, by an unknown artist.