The I Ching or Book of Changes (7 page)

While we were in the midst of this work, the horror of the world war broke in upon us. The Chinese scholars were scattered to the four winds, and Mr. Lao left for Ch’ü-fou, the home of Confucius, to whose family he was related. The translation of the Book of Changes was laid aside, although during the siege of Tsingtao, when I was in charge of the Chinese Red Cross, not a day passed on which I did not devote some time to the study of ancient Chinese wisdom. It was a curious coincidence that in the encampment outside the city, the besieging Japanese commander, General Kamio, was reading the Book of Mencius in his moments of relaxation, while I, a German, was similarly delving into Chinese wisdom in my free hours. Happiest of all, however, was an old Chinese who was so wholly absorbed in his sacred books that not even a grenade falling at his side could disturb his calm. He reached out for it—it was a dud—then drew back his hand and, remarking that it was very hot, forthwith returned to his books.

Tsingtao was captured. Despite all sorts of other tasks, I again found time for intensive work on the translation, but the teacher with whom I had begun the work was now far away, and it was impossible for me to leave Tsingtao. In the midst of my perplexities, it made me very happy to receive a letter from Mr. Lao saying that he was ready to go on with our interrupted studies. He came, and the translation was brought to completion. Those were rare hours of inspiration that I spent with my aged master. When the work in its essential features was almost finished, fate called me back to Germany. In the meantime my venerable master departed this world.

Habent sua fata libelli

. In Germany I seemed to be as far removed as possible from ancient Chinese wisdom, although in Europe also many a word of counsel from the mysterious book has here and there fallen on fertile soil. Hence my joy and surprise were great indeed when in the house of a good friend in Friedenau, I found the Book of Changes—and in a beautiful edition for which I had hunted in vain through all the bookshops of Peking. My friend moreover proved a friend indeed, in making this happy find my permanent possession. Since then the book has accompanied me on many a journey, halfway round the globe.

I came back to China. New tasks claimed me. In Peking a wholly new world, with other people and other interests, opened up before me. Nonetheless, here too help soon came to hand in many ways, and in the warm days of a Peking summer the work was finally brought to conclusion. Recast again and again, the text has at last attained a form that—though it falls far short of my wish—makes it possible for me to give the book to the world. May the same joy in pure wisdom be the part of those who read the translation as was mine while I worked upon it.

RICHARD WILHELM

Peking, in the summer of 1923

BY

R

ICHARD

W

ILHELM

The Book of Changes—

I Ching

in Chinese—is unquestionably one of the most important books in the world’s literature. Its origin goes back to mythical antiquity, and it has occupied the attention of the most eminent scholars of China down to the present day. Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text. Therefore it may safely be said that the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years has gone into the making of the

I Ching

. Small wonder then that both of the two branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Taoism, have their common roots here. The book sheds new light on many a secret hidden in the often puzzling modes of thought of that mysterious sage, Lao-tse, and of his pupils, as well as on many ideas that appear in the Confucian tradition as axioms, accepted without further examination.

Indeed, not only the philosophy of China but its science and statecraft as well have never ceased to draw from the spring of wisdom in the

I Ching

, and it is not surprising that this alone, among all the Confucian classics, escaped the great burning of the books under Ch’in Shih Huang Ti.

1

Even the commonplaces of everyday life in China are saturated with its influence. In going through the streets of a Chinese city, one will find, here and there at a street corner, a fortune teller sitting behind a neatly covered table, brush and tablet at hand, ready to draw from the ancient book of wisdom pertinent counsel and information on life’s minor perplexities. Not only that, but the very signboards adorning the houses—perpendicular wooden panels done in gold on black lacquer—are covered with inscriptions whose flowery language again and again recalls thoughts and quotations from the

I Ching

. Even the policy makers of so modern a state as Japan, distinguished for their astuteness, do not scorn to refer to it for counsel in difficult situations.

In the course of time, owing to the great repute for wisdom attaching to the Book of Changes, a large body of occult doctrines extraneous to it—some of them possibly not even Chinese in origin—have come to be connected with its teachings. The Ch’in and Han dynasties

2

saw the beginning of a formalistic natural philosophy that sought to embrace the entire world of thought in a system of number symbols. Combining a rigorously consistent, dualistic yin-yang doctrine with the doctrine of the “five stages of change” taken from the Book of History,

3

it forced Chinese philosophical thinking more and more into a rigid formalization. Thus increasingly hairsplitting cabalistic speculations came to envelop the Book of Changes in a cloud of mystery, and by forcing everything of the past and of the future into this system of numbers, created for the

I Ching

the reputation of being a book of unfathomable profundity. These speculations are also to blame for the fact that the seeds of a free Chinese natural science, which undoubtedly existed at the time of Mo Ti

4

and his pupils, were killed, and replaced by a sterile tradition of writing and reading books that was wholly removed from experience. This is the reason why China has for so long presented to Western eyes a picture of hopeless stagnation.

Yet we must not overlook the fact that apart from this mechanistic number mysticism, a living stream of deep human wisdom was constantly flowing through the channel of this book into everyday life, giving to China’s great civilization that ripeness of wisdom, distilled through the ages, which we wistfully admire in the remnants of this last truly autochthonous culture.

What is the Book of Changes actually? In order to arrive at an understanding of the book and its teachings, we must first of all boldly strip away the dense overgrowth of interpretations that have read into it all sorts of extraneous ideas. This is equally necessary whether we are dealing with the superstitions and mysteries of old Chinese sorcerers or the no less superstitious theories of modern European scholars who try to interpret all historical cultures in terms of their experience of primitive savages.

5

We must hold here to the fundamental principle that the Book of Changes is to be explained in the light of its own content and of the era to which it belongs. With this the darkness lightens perceptibly and we realize that this book, though a very profound work, does not offer greater difficulties to our understanding than any other book that has come down through a long history from antiquity to our time.

1.

T

HE

U

SE OF THE

B

OOK OF

C

HANGES

The Book of Oracles

At the outset, the Book of Changes was a collection of linear signs to be used as oracles.

6

In antiquity, oracles were everywhere in use; the oldest among them confined themselves to the answers yes and no. This type of oracular pronouncement is likewise the basis of the Book of Changes. “Yes” was indicated by a simple unbroken line (———), and “No” by a broken line (— —). However, the need for greater differentiation seems to have been felt at an early date, and the single lines were combined in pairs:

To each of these combinations a third line was then added. In this way the eight trigrams

7

came into being. These eight trigrams were conceived as images of all that happens in heaven and on earth. At the same time, they were held to be in a state of continual transition, one changing into another, just as transition from one phenomenon to another is continually taking place in the physical world. Here we have the fundamental concept of the Book of Changes. The eight trigrams are symbols standing for changing transitional states; they are images that are constantly undergoing change. Attention centers not on things in their state of being—as is chiefly the case in the Occident—but upon their movements in change. The eight trigrams therefore are not representations of things as such but of their tendencies in movement.

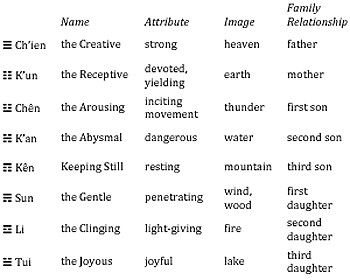

These eight images came to have manifold meanings. They represented certain processes in nature corresponding with their inherent character. Further, they represented a family consisting of father, mother, three sons, and three daughters, not in the mythological sense in which the Greek gods peopled Olympus, but in what might be called an abstract sense, that is, they represented not objective entities but functions.

A brief survey of these eight symbols that form the basis of the Book of Changes yields the following classification:

The sons represent the principle of movement in its various stages—beginning of movement, danger in movement, rest and completion of movement. The daughters represent devotion in its various stages—gentle penetration, clarity and adaptability, and joyous tranquility.

In order to achieve a still greater multiplicity, these eight images were combined with one another at a very early date, whereby a total of sixty-four signs was obtained. Each of these sixty-four signs consists of six lines, either positive or negative. Each line is thought of as capable of change, and whenever a line changes, there is a change also of the situation represented by the given hexagram. Let us take for example the hexagram K’un, THE RECEPTIVE, earth:

It represents the nature of the earth, strong in devotion; among the seasons it stands for late autumn, when all the forces of life are at rest. If the lowest line changes, we have the hexagram, Fu, RETURN:

The latter represents thunder, the movement that stirs anew within the earth at the time of the solstice; it symbolizes the return of light.