The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy (74 page)

Read The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy Online

Authors: Mervyn Peake

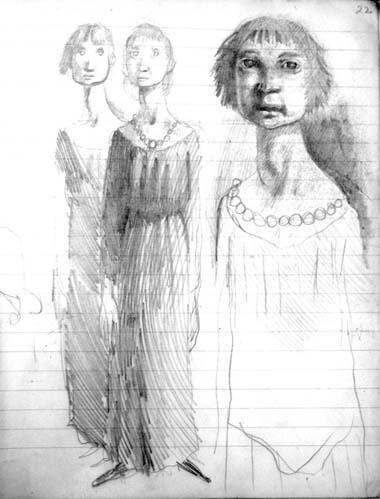

Then the aunts arose, all stuck about with purple and made their way, hand in hand, to the amazed gathering on the sands.

Steerpike’s lesson had been well digested, and they walked solemnly past the Doctor, Fuchsia, Irma and Nannie Slagg and into the trees; and, turning to their left along a hazel ride, proceeded, in a kind of sodden trance, in the direction of the Castle.

‘It beats me, Doctor! Beats me completely!’ shouted the youth in the water.

‘You surprise me, dear boy!’ cried the Doctor. ‘By all that’s amphibious, you surprise me. Have a heart, dear child, have a heart, and swim away – we’re so tired of the sight of your stomach.’

‘Forgive its magnetism!’ replied Steerpike, who dived back under water and was next to be seen some distance off, swimming steadily in the direction of the Raft Makers.

Fuchsia, watching the sunlight flashing on the wet arms of the now distant boy, found that her heart was pounding. She mistrusted his eyes. She was repelled by his high, round forehead and the height of his shoulders. He did not belong to the Castle as she knew it, but her heart beat, for he was alive – oh, so alive! and adventurous; and no one seemed to be able to make him feel humble. As he had answered the Doctor his eyes had been on her. She did not understand. Her melancholy was like a darkness in her; but when she thought of him it seemed that through the darkness a forked lightning ran.

‘I’m going back now,’ she said to the Doctor. ‘Tonight we will meet, thank you. Come on, Nannie. Good-bye, Miss Prunesquallor.’

Irma made a kind of curling movement with her body and smiled woodenly.

‘Good day,’ she said, ‘It has been delightful. Most. Bernard, your arm. I said – your

arm

.’

‘You did, and there’s no doubt about it, snow-blossom. I heard you,’ said her brother. ‘Ha! ha! ha! And here it is. An arm of trembling beauty, it’s every pore agog for the touch of your limp fingers. You wish to take it? You shall. You shall take it – but seriously, ha! ha! ha! Take it seriously. I pray you, sweet frog; but do let me have it back sometime. Let us away, Fuchsia, for now, good-bye. We part, only to meet.’

Ostentatiously he raised his left elbow and Irma, lifting her parasol over her head, her hips gyrating and her nose like a needle pointing the way, took his arm and they moved into the shadows of the trees.

Fuchsia lifted Titus and placed him over her shoulder, while Nannie folded up the rust-coloured rug, and they in their turn began the homeward journey.

Steerpike had reached the further shore and the party of men had resumed their

détour

of the lake, the chestnut boughs across their shoulders. The youth moved jauntily ahead of them, spinning the swordstick.

Long after the drop of lake water had fallen from the ilex leaf and the myriad reflections that had floated on its surface had become a part of the abactina of what had gone for ever, the head at the thorn-prick window had remained gazing out into the summer.

It belonged to the Countess. She was standing on a ladder, for only in such a way could she obtain a view through that high, ivy-cluttered opening. Behind her the shadowy room was full of birds.

Blobs of flame on the dark crimson wallpaper smouldered, for a few sunbeams shredded their way past her head and struck the wall with silent violence. They were entirely motionless in the half light and burned without a flicker, forcing the rest of the room into still deeper shade, and into a kind of subjugated motion, a counter-play of volumes of many shades between the hues of deep ash-grey and black.

It was difficult to see the birds, for there were no candles lighted. The summer burned beyond the small high window.

At last the Countess descended the ladder, step after mammoth step, until both feet on the ground she turned about, and began to move to the shadowy bed. When she reached its head she ignited the wick of a half-melted candle and, seating herself at the base of the pillows, emitted a peculiarly sweet, low, whistling note from between her great lips.

For all her bulk it was as though she had, from a great winter tree, become a summer one. Not with leaves was she decked, but, thick as foliage, with birds. Their hundred eyes twinkled like glass beads in the candlelight.

‘Listen,’ she said, ‘We’re alone. Things are bad. Things are going wrong. There’s evil afoot. I know it.’

Her eyes narrowed. ‘But let ’em try. We can bide our time. We’ll hold our horses. Let them rear their ugly hands, and by the Doom, we’ll crack ’em chine-ways. Within four days the Earling – and then I’ll take him, babe and boy – Titus the Seventy-seventh.’

She rose to her feet, ‘God shrive my soul, for it’ll need it!’ she boomed, as the wings fluttered about her and the little claws shifted for balance. ‘God shrive it when I find the evil thing! For absolution, or no absolution – there’ll be

satisfaction

found.’ She gathered some cake crumbs from a nearby crate, and placed them between her lips. At the trotting sound of her tongue a warbler pecked from her mouth, but her eyes had remained half closed, and what could be seen of her iris was as hard and glittering as a wet flint.

‘Satisfaction,’ she repeated huskily, with something purr-like in the heavy-sounding syllables. ‘In Titus it’s all centred. Stone and mountain – the Blood and the Observance. Let them touch him. For every hair that’s hurt I’ll stop a heart. If grace I have when turbulence is over – so be it; and if not – what then?’

Something in a white shroud was moving towards the door of the twins’ apartment. The Castle was asleep. The silence like space. The Thing was inhumanly tall and appeared to have no arms.

In their room the aunts sat holding each other by the empty grate. They had been waiting so long for the handle of the door to turn. This is now what it began to do. The twins had their eyes on it. They had been watching it for over an hour – the room ill lit – their brass clock ticking. And then, suddenly, through the gradually yawning fissure of the door the Thing entered, its head scraping the lintel – its head grinning and frozen, was the head of a skull.

They could not scream. The twins could not scream. Their throats were contracted; their limbs had stiffened. The bulging of their four identical eyes was ghastly to see, and as they stood there, paralysed, a voice from just below the grinning skull cried:

‘Terror! terror! terror! pure; naked; and bloody!’

And the nine-foot length of sheet moved into the room.

Old Sourdust’s skull had come in useful. Balanced on the end of the sword-stick, and dusted with phosphorus, the sheet hanging vertically down its either side, and kept in place by a tack through the top of the cranium, Steerpike was able to hold it three feet above his own head and peer through a slit he had made in the sheet at his eye level. The white linen fell in long sculptural folds to the floor of the room.

The twins were the colour of the sheet. Their mouths were wide open and their screams tore inwards at their bowels for lack of natural vent. They had become congealed with an icy horror, their hair, disentangling from knot and coil, had risen like pampas grass that lifts in a dark light when gusts prowl shuddering and presage storm. They could not even cling more closely together, for their limbs were weighted with cold stone. It was the end. The Thing scraped the ceiling with its head and moved forward noiselessly in one piece. Having no human possibility of height, it had

no

height. It was not a tall ghost – it was immeasurable; Death walking like an element.

Steerpike had realized that unless something was done it would be only a matter of time before the twins, through the loose meshwork of their vacant brains, divulged the secret of the Burning. However much they were in his power he could not feel sure that the obedience which had become automatic in his presence would necessarily hold when they were among others. As he now saw it, it seemed that he had been at the mercy of their tongues ever since the Fire – and he could only feel relief that he had escaped detection – for until now he had had hopes that vacuous as they were, they would be able to understand the peril in which, were any suspicion to be attached to them, they would stand. But he now realized that through terrorism and victimization alone could loose lips be sealed. And so he had lain awake and planned a little episode. Phosphorus, which along with the poisons he had concocted in Prunesquallor’s dispensary, and which as yet he had found no use for – his swordstick, as yet unsheathed, save when alone he polished the slim blade, and a sheet. These were his media for the concoction of a walking death.

And now he was in their room. He could watch them perfectly through the slit in the sheet. If he did not speak now, before the hysterics began, then they would hear nothing, let alone grasp his meaning. He lifted his voice to a weird and horrible pitch.

‘I am Death!’ he cried. ‘I am all who have died. I am the death of Twins. Behold! Look at my face. It is naked. It is bone. It is Revenge.

Listen

. I am the One who strangles.’

He took a further pace towards them. Their mouths were still open and their throats strained to loose the clawing cry.

‘I come as Warning! Warning! Your throats are long and white and ripe for strangling. My bony hands can squeeze all breath away … I come as Warning!

Listen

!’

There was no alternative for them. They had no power.

‘I am Death – and I will talk to you – the Burners. Upon that night you lit a crimson fire. You burned your brother’s heart away! Oh, horror!’

Steerpike drew breath. The eyes of the twins were well nigh upon their cheekbones. He must speak very simply.

‘But there is yet a still more bloody crime. The crime of speech. The crime of Mentioning, Mentioning. For this, I murder in a darkened room.

I

shall be watching. Each time you move your mouths

I

shall be watching. Watching. Watching with my enormous eyes of bone. I shall be listening. Listening, with my fleshless ears: and my long fingers will be itching … itching. Not even to each other shall you speak. Not of your crime. Oh, horror! Not of the crimson Fire.

‘My cold grave calls me back, but shall I answer it? No! For I shall be beside

you

for ever. Listening, listening; with my fingers itching. You will not see me … but I shall be here … there … and wherever you go … for evermore. Speak not of Fire … or Steerpike … Fire – or Steerpike, your protector, for the sake of your long throats … Your long white throats.’

Steerpike turned majestically. The skull had tilted a little on the point of the swordstick, but it did not matter. The twins were ice bound in an arctic sea.

As he moved solemnly through the doorway, something grotesque, terrifying, ludicrous in the slanting angle of the skull – as though it were listening … gave emphasis to all that had gone before.

As soon as he had closed the door behind him he shed himself of the sheet and, wrapping the skull in its folds, hid it from view among some lumber that lay along the wall of the passage.

There was still no sound from the room. He knew that it would be fruitless to appear the same evening. Whatever he said would be lost. He waited a few moments, however, expecting the hysteria to find a voice, but at length began his return journey. As he turned the corner of a distant passageway, he suddenly stopped dead. It had begun. Dulled as it was by the distance and the closed doors, it was yet horrifying enough – the remote, flat, endless screaming of naked panic.

When, on the evening of the next day, he visited them he found them in bed. The old woman who smelt so badly had brought them their meals. They lay close together and were obviously very ill. They were so white that it was difficult to tell where their faces ended and the long pillow began.