The Indigo King (2 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

In the centuries that would pass, the spacious stone room known as Solitude would fill with an accumulation of culture; not by design, but because those who would eventually come to seek the occupant’s skills would feel the obligation to bring something, anything, as gifts, or perhaps tribute. But that was in a time yet to come. In the present moment, it was empty save for the items he’d brought with him: a torn robe, an empty scabbard, a quill and half-filled bottle of ink, and as many rolls of parchment as he could carry.

When he entered, the door had swung shut behind him. He knew without touching it that it had locked, and also, with less assurance, that it would probably not be opened again for many years.

He had once had a name—several names, in fact—all of which were irrelevant now. In his youth he had aspired to be a great man, and had been afforded many opportunities to fulfill that destiny; but far too late, he learned that it was perhaps better to be a good man, who nevertheless aspires to do great things. The distinction had never mattered to him much before.

Solitude had not been created for him, but he took possession of it with the reluctant ease of an heir who receives an unexpected and unwanted inheritance. He laid the robe in one corner, and the scabbard in another, then sat cross-legged in the center of Solitude to examine the rolls of parchment.

Some of them contained drawings and notations; a few, directions that may or may not have been accurate, to places that may or may not have existed. They were maps, more or less, and at one time it had been his driven purpose to create them. But that was before, when his sight was clearer and his motives more pure. Somehow, somewhen, he had lost his way—and in the process, ended up on a path that had brought him here, to Solitude.

Still, he could not help but wonder: Was it the first step on that path, or the last, that had proven to be his undoing? He looked down at the maps. The oldest had been made by his hand more than a millennium before; but the newest of them had been begun, then abandoned, a century ago. He examined it more closely and saw that the delicate lines were obscured by blood—the same that marked the cloak and scabbard as symbols of his shame.

Some things cannot be undone. But someone who is lost might still return to the proper path, if they only have something to show them the way.

Taking the quill in hand, he dipped the point into the bottle. Whether the place he drew existed then didn’t matter—it would, eventually. All that mattered now was that he was, at long last, finding his purpose again. Would that he had done so a day earlier. Just one day.

As he began to draw, tears streamed from his eyes, dropping to the parchment, where they mingled freely with the ink and blood in equal measure. The man in Solitude was a mapmaker once more.

The Booke of Dayes

Hurrying along one of the tree-lined paths at Magdalen College in Oxford, John glanced up at the cloud-clotted sky and decided that he rather liked the English weather. Constant clouds made for soft light; soft light that cast no shadows. And John liked to avoid shadows as much as possible.

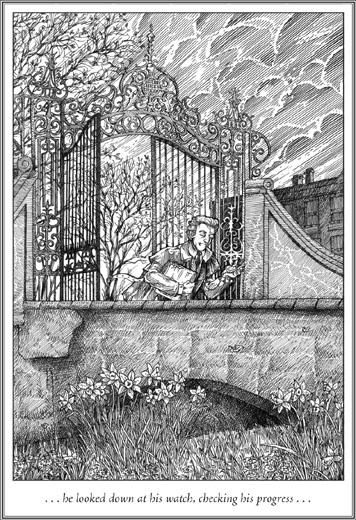

As he passed through the elaborate gate that marked the entrance to Addison’s Walk, he looked down at his watch, checking his progress, then looked again. The watch had stopped, and not for the first time. It had been a gift from his youngest child, his only daughter, and while her love in the gift was evident, the selection had been made from a child’s point of view and was therefore more aesthetic than practical. The case was burnished gold (although it was most certainly gold-colored tin), the face was painted with spring flowers, and on the back was the embossed image of a frog wearing a bonnet.

John had absentmindedly pulled it out of his pocket during one of the frequent gatherings of his friends at Magdalen, much to their amusement. Barfield in particular loved to approach him now at inopportune moments just to ask the time—and hopefully embarrass John in the process.

John sighed and tucked the watch back in his pocket, then pulled his collar tighter and hurried on. He was probably already late for the dinner he’d been invited to at the college, and although he had always been punctual (mostly), events of recent years had made him much more aware of the consequences tardiness can bring.

Five years earlier, after a sudden and unexpected journey to the Archipelago of Dreams, he’d found himself a half hour late for an evening with visiting friends that had been planned by his wife. Even had he not taken an oath of secrecy regarding the Archipelago, he would scarcely have been able to explain that he was late because he’d been saving Peter Pan’s granddaughter and thousands of other children from the Pied Piper, and had only just returned via a magic wardrobe in Sir James Barrie’s house, and so had still needed to drive home from London.

His wife, however, still made the occasional remark about his having been late for the party. So John had since resolved to be as punctual as possible in every circumstance. And tonight he was certain that Jack would not want to be on his own for long, even if the third member of their dinner meeting was their good and trusted friend, Hugo Dyson.

Hugo had become part of a loose association of like-minded fellows, centered around Jack and John, who gathered together to read, discuss, and debate literature, Romanticism, and the nature of the universe, among other things. The group had evolved from an informal club at Oxford that John had called the Coalbiters, which was mostly concerned with the history and mythology of the Northern lands. One of the members of the current gathering referred to them jokingly as the “not-so-secret secret society,” but where John and Jack were concerned, the name was more ironic than funny. They frequently held other meetings attended only by themselves and their friend Charles, as often as he could justify the trip from London to Oxford, in which they discussed matters that their colleagues would find impossible to believe. For rather than discussing the meaning of metaphor in ancient texts of fable and fairy tale, what was discussed in this

actually

secret secret society were the fables and fairy tales themselves … which were

real

. And existed in another world just beyond reach of our own. A world called the Archipelago of Dreams.

John, Jack, and Charles had been recruited to be Caretakers of the

Imaginarium Geographica

, the great atlas of the Archipelago. Accepting the job brought with it many other responsibilities, including the welfare of the Archipelago itself and the peoples within it. The history of the atlas and its Caretakers amounted to a secret history of the world, and sometimes each of them felt the full weight of that burden; for events in the Archipelago are often mirrored in the natural world, and what happens in one can affect the other.

In the fourteen years since they first became Caretakers, all three men had become distinguished as both scholars and writers in and around Oxford, as had been the tradition with other Caretakers across the ages. There were probably many other creative men and women in other parts of the world who might have had the aptitude for it, but the pattern had been set centuries earlier by Roger Bacon, who was himself an Oxford scholar and one of the great compilers of the Histories of the Archipelago.

The very nature of the

Geographica

and the accompanying Histories meant that discussing them or the Archipelago with anyone in the natural world was verboten. At various points in history, certain Caretakers-in-training had disagreed with this doctrine and had been removed from their positions. Some, like Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle, were nearly eaten by the dragons that guarded the Frontier, the barrier between the world and the Archipelago, before giving up the job. Others, like the adventurer Sir Richard Burton, were cast aside in a less dramatic fashion but had become more dangerous in the years that followed.

In fact, Burton had nearly cost them their victory in their second conflict with the Winter King—with his shadow, to be more precise—and had ended up escaping with one of the great Dragon-ships. He had not been seen since. But John suspected he was out there somewhere, watching and waiting.

Burton himself may have been the best argument for Caretaker secrecy. The knowledge of the Archipelago bore with it the potential for great destruction, but Burton was blind to the danger, believing that knowledge was neither good nor evil—only the uses to which it was put could be. It was the trait that made him a great explorer, and an unsuitable Caretaker.

Because of the oath of secrecy, there was no one on Earth with whom the three Caretakers could discuss the Archipelago, save for their mentor Bert, who was in actuality H. G. Wells, and on occasion, James Barrie. But Barrie, called Jamie by the others, was the rare exception to Burton’s example: He was a Caretaker who gave up the job willingly. And as such, John had realized early on that the occasional visit to reminisce was fine—but Jamie wanted no part of anything of substance that dealt with the Archipelago.

What made keeping the secret difficult was that John, Jack, and Charles had found a level of comfortable intellectualism within their academic and writing careers. A pleasant camaraderie had developed among their peers at the colleges, and it became more and more tempting to share the secret knowledge that was theirs as Caretakers. John had even suspected that Jack may have already said something to his closest friend, his brother Warnie—but he could hardly fault him for that. Warnie could be trusted, and he had actually seen the girl Laura Glue, when she’d crashed into his and Jack’s garden, wings askew, five years earlier, asking about the Caretakers.

But privately, each of them had wondered if one of their friends at Oxford might not be inducted into their circle as an apprentice, or Caretaker-in-training of sorts. After all, that was how Bert and his predecessor, Jules Verne, had recruited their successors. In fact, Bert still maintained files of study on potential Caretakers, young and old, for his three protégés to observe from afar. Within the circle at Oxford, there were at least two among their friends who would qualify in matters of knowledge and creative thinking: Owen Barfield and Hugo Dyson. John expected that sometime in the future, he, Jack, and Charles would likely summon one (or both) colleagues for a long discussion of myth, and history, and languages, and then, after a hearty dinner and good drink, they would unveil the

Imaginarium Geographica

with a flourish, and thus induct their fellow or fellows into the ranks of the Caretakers. Other candidates might be better qualified than the Oxford dons, but familiarity begat comfort, and comfort begat trust. And in a Caretaker, trust was one of the most important qualities of all.

But none of them had anticipated having such a meeting as a matter of necessity, under circumstances that might have mortal consequences for one of their friends. Among them, Jack especially was wary of this. He had lost friends in two worlds and was reluctant to put another at risk if he could help it.

He had requested that all three of them meet for dinner with Hugo Dyson on the upcoming Saturday rather than their usual Thursday gathering time, but as it turned out, Charles was doing research for a novel in the catacombs beneath Paris and could not be reached. He’d been expected back that very day, but as they had heard nothing from him, and he had not yet appeared back in London, John and Jack decided that the meeting was too important to delay, and they confirmed the appointment with Hugo for that evening. It was agreed that the best place for it was in Jack’s rooms at Magdalen. They met there often, and so no one observing them would find anything amiss; but the rooms also afforded a degree of privacy they could not get in the open dining halls or local taverns, should the discussion turn to matters best kept secret.

This was almost inevitable, John realized with a shudder of trepidation, given the nature of the matter he and Jack needed to broach with Hugo. Oddly enough, it was actually Charles who was responsible for setting the events in motion, or rather, a small package that had been addressed to him and that he’d subsequently forwarded to Jack at Magdalen. Charles worked at the Oxford University Press, which was based in London, and very few people knew of his connection to Jack at all—much less knew enough to address the parcel, “Mr. Charles Williams, Caretaker.” Charles sent it to Jack, with the instruction that he open it together with John—and Hugo Dyson.

Invoking the title of Caretaker meant that the parcel involved the Archipelago. And Charles’s request that Hugo be invited meant that whether their colleague was ready for it or not, it might be time to reveal the

Geographica

to him.

When they were not adding notations—or more rarely, new maps—John kept the atlas in his private study, inside an iron box bound with locks of silver and stamped with the seal of the High King of the Archipelago, the Caretakers, and the mark of the extraordinary man who created it, who was called the Cartographer of Lost Places. In that box it was the most secure book in all the world, but now it was wrapped in oilcloth and tucked under John’s left arm as he walked through Magdalen College. Still safe, if not secure.

John shivered and hunched his shoulders as he approached the building where Jack’s rooms were, then took the steps with a single bound and opened the front door.

The rooms were spare but afforded a degree of elegance by the large quantity of rare and unusual books, which reflected a wealth of selection rather than accumulation. A number of volumes in varying sizes were neatly stacked in all the corners of the rooms and along the tops of the low shelves that were common in Oxford, which all the dons hated. Jack commented frequently that they’d probably been manufactured by dwarves, just to irritate the taller men who’d end up using them.

As John had feared, Hugo was already there, sitting on a big Chesterfield sofa in the center of the sitting room. He was being poured a second cup of Darjeeling tea by their host, who looked wryly at John as he came in.

“The frog in a bonnet set you back again, dear fellow?” said Jack.

“I’m afraid so,” John replied. “The dratted thing just won’t stay wound.”

“Hah!” chortled Hugo. “Time for a new watch, I’d say. Time. For a watch. Hah! Get it?”

Jack rolled his eyes, but John gave a polite chuckle and took a seat in a shabby but comfortable armchair opposite Hugo. The man was a scholar, but he wore the perpetual expression of someone who anticipates winning a carnival prize: anxious but cheerily hopeful. That, combined with his deep academic knowledge of English and his love of truth in all forms, made him a friend both John and Jack valued. Whether he was suited for the calling of Caretaker, however, was yet to be determined.

The three men finished their tea and then ate a sumptuous meal of roast beef, new potatoes, and a dark Irish bread, topped off with sweet biscuits and coffee. John noted that Jack then brought out the rum—much sooner than usual, and with a lesser hesitation than when Warnie was with them—and with the rum, the parcel that had been sent to Charles.

“Ah, yes,” said Hugo. “The great mystery that has brought us all together.” He leaned forward and examined the writing on the package. “Hmm. This wouldn’t be Charles Williams the writer, would it?”

Jack and John looked at each other in surprise. Few of their associates in Oxford knew of Charles, but then again, Charles did have his own reputation in London as an editor, essayist, and poet. His first novel,

War in Heaven

, had come out only the year before, and it was not particularly well known.

“Yes, it is,” said John. “Have you read his work?”

“Not much of it, I’m afraid,” Hugo replied. “But I’ve had my own work declined by the press, so I might find I like his writing more if my good character prevails when I do read it.

“I’m familiar with his book,” continued Hugo, “because the central object in the story is the Holy Grail.”