The Indigo King (7 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

“Must be low tide,” John observed, “but the beach seems awfully parched.”

Chaz chuckled. “‘Tis, ‘tis,” he said in agreement. “Been low tide for almost two hundred years, as I heard it said. The ocean’s still out there, somewheres, but no souls alive has seen it.”

“Strange pier,” Jack said. “If there’s no water, where do you moor the boats?”

“Hsst!” Chaz hissed, looking behind them. “You can’t just go round sayin’ words like that. Words kill, you know.”

“Sorry,” said Jack.

“Is that him?” John asked, pointing.

At the end of the pier, a shadow stood against a piling. A shadow with a very familiar shape.

John began to move closer, but Chaz motioned for him to hold back. Instead Chaz stepped to the far right side of the pier, where he could be seen in the dim light—but without getting too close to the figure at the end of the pier.

The shadow raised its head in alarm, then lowered it in resignation.

“Whatever it is you’ve come about, Chaz, I want no part of it. Go back to your game-playing with the Wicker Men, or better yet, go play some pipes outside the bone towers, and let the giants have some fun with you. I don’t care either way—just leave me be.”

“Weren’t my call to come seeking you either, you old goat,” Chaz retorted, “but I run into some fellows who says they knows you. Calls you ‘Bert’ or summat.”

At this the shadow stood upright, startled. “Bert? There’s no one else still alive who would use that name, not in

this

world, not unless …”

He pushed away from the piling where he’d been braced, and hobbled out into the hazy light. For everyone but Chaz, there was a shock of recognition, and for John and Jack, a further shock of seeing nightmares made real.

It was indeed Bert. But he had been

changed

.

The cheerily ruffled tatterdemalion of their first meeting was barely in evidence here. The clothes and hat were the same, but threadbare and shabby. He was thin, nearly emaciated, and his face haggard and drawn. There was no spark in his eyes, no twinkle. Neither of them had ever seen him without the twinkle, even in the grimmest of circumstances. But then again, neither of them had seem him without all his limbs, either.

Bert supported himself by gripping a small ash walking stick with his left hand—his only hand. His other sleeve was folded and pinned just below his elbow. And in place of his right leg, fastened just under the knee was a piece of wood wrapped in leather, which ended with a crude wooden foot inside his shoe.

Before John or Jack could say anything, Bert threw aside his stick and hobbled forward, grabbing John by the lapels. Weakly, but driven by surprise and rage, his hand shook as the younger man tried to steady him. Bert pressed close, eyes wild, and all but screamed at John.

“Where have you been? Where … have … you …

been?!

”

The Serendipity Box

Bert! “John said in choked astonishment. “You know us? You really know us?”

“Of course I know you, John,” the ragged old man said, finally letting go of John’s coat and brushing him away. “I gave you the

Geographica

. I helped the three of you learn your roles in the great clockwork mechanism of things that are. I stood by you against a great evil, and we saved the world, once. And then you let it degrade to … to … this,” he spat, gesturing with his good arm. “Here, you. Badger. Give me my stick.”

Fred jumped forward and retrieved the short ash staff, handing it to the old man. Neither he nor Uncas understood what was taking place, and so they remained quiet while the humans played out the drama.

Bert stood a few feet from John and Jack, forming a rough triangle, but he refused to look at either of them—not directly. Chaz stood farther back, observing.

“Fourteen years,” Bert wheezed. “We came here fourteen years ago, to … heh …

SAVE

you … to

HELP

you …”

“You said ‘we,’ Bert,” Jack said, interrupting. “Who else came with you? Surely not Aven?”

“No, not Aven,” Bert replied. “Your pretty ladylove stayed in the Archipelago, where she needed to be. She doesn’t love you, you know,” he added, almost conspiratorially. “Never did. Didn’t love the potboy, either. No, Nemo was her companion, but you fixed that, didn’t you, Jack?”

In earlier years Jack would have reddened at this and become flustered. But he’d matured a great deal in the intervening time, and could face his own shortcomings and mistakes foursquare, as a man is supposed to do.

“I stopped feeling responsible for that a long time ago, Bert,” he said calmly. “James Barrie told me things about Nemo, and you, and …” He stopped. “Verne. You came here with Jules Verne.”

Bert sighed heavily and turned his back to them before answering. “Yes,” he said finally. “Jules and I came here together. We came …

here

.…”

Without warning, the old man suddenly burst into tears. “Why did you have to bring her up, Jack? Why did you have to mention Aven, now that I’d finally nearly forgotten about her?”

Jack started to reply, but John silenced him with a gesture. Bert was speaking from a long, deep pain, and perhaps they might learn something of what was happening.

“If she’d been killed in battle, I might have been able to live with it,” Bert sobbed. “But here, after what’s happened, it’s as if she never existed! She is worse than dead!”

“The Lady Aven is not dead,” came a soft voice. “I saw her myself just yesterday.”

Fred was standing nearby, head bowed and paws folded respectfully, but when he spoke his voice was firm with conviction. “She is alive. Maybe not here, where we are, but somewheres. She is. And when Scowler John and Scowler Jack, and, uh, Mister Chaz help us t’ get back there, maybe you can come with us and see for yourself.”

At first Bert reacted in rage, raising the ash stick to strike at the little creature. But Fred didn’t move. He barely flinched, and closed his eyes to receive the blow.

Seeing this, Bert lowered the stick, then fell to his knees and grasped the badger, pulling Fred to his chest. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, little child of the Earth,” Bert said through muffled sobs. “I will not strike you. I won’t. It’s just … It’s been so long.…”

Fred hugged the old traveler, and after a moment, Uncas moved in to do so as well. “It be all right,” said Uncas gently.

“Animal logic,” Jack said to John. “Loyalty is all, and all things may be forgiven.”

“We should go inside,” said Chaz. “The sun will be coming up soon.”

“Yes,” Bert agreed, rising and wiping his eyes. “We have a great deal to discuss.”

With the badgers supporting him on either side, Bert moved down the pier to the bridge that connected it to the house. John followed behind, but Jack pulled Chaz aside.

“If this is indeed ‘our’ Bert,” Jack whispered, “how has he survived?

You

knew just where to find him. Wouldn’t the king have killed him long before now?”

“He has, in years past, proved himself to be a friend to the king,” Chaz replied, “or at least, wise enough to seem as such.”

“And this,” Jack said, indicating the damaged man walking ahead of them, “is how the king treats his friends?”

Chaz shrugged. “Someone asked him that once. And th’ king laughed an’ said, ‘A friend this valuable you can’t eat all at once.’”

Bert took them all inside the little shack, where he lit two candles, which he placed at opposite ends of the cramped quarters. For a single person, the accommodations were tight; for four men and two badgers, it was practically claustrophobic. There was a table and only one chair, which Bert took. The others sat on the floor, except for Chaz, who remained standing nervously in the doorway.

“You’ll have to forgive my lack of hospitality,” Bert told the others. “I’d offer you tea, but I haven’t any tea. I’d offer you brandy, but I haven’t any brandy. In fact, I don’t even have any crackers to give you.”

“We did,” said Uncas, “but there was an emergency.”

“There still is,” said Jack.

“That’s a shame,” said Bert, “to run out of crackers before you’ve run out of emergency. And in Albion, it’s always an emergency.”

“The king, whoever he is, sounds like an utter despot,” John observed.

“Well said, John,” said Bert, “for he is just that. A despot. A petty, cruel dictator who hates himself and takes it out on everyone else. He suffers, and so makes the world suffer too.”

“That sounds awfully familiar,” said Jack.

“More than you know,” said Bert. “You’ve met him. Killed him, actually, more or less.”

“That’s impossible,” said John.

“Improbable, but clearly not impossible,” Bert corrected. “In the world you came from, the Winter King fell to his death in the year 1917. But here it is the one thousand four hundred and fourth year of the reign of our Lord and King, Imperius Rex, Mordred the First.”

It took some time for the reunited friends to explain what had been happening to them, and Bert listened to their accounting of the situation with Hugo Dyson without comment. When they at last had finished explaining, he nodded sadly.

“I begin to understand, at long last,” he said, still unwilling to look at any of them directly. “If Hugo went back to the sixth century, then he changed history. And everything proceeded apace from there to what we see now, today. Something that happened in the past gave Mordred the means to conquer and rule and emerge victorious against all opposition—if there ever was any.”

“Why do you still know us, Bert?” asked Jack. “Chaz is obviously what Charles became in this timeline where he never knew us—but you’re still our Bert.”

“Jules and I left Paralon right after the War of the Winter King,” said Bert. “He had come across a passage in a future history that mentioned the reemergence of Mordred, and so we returned here to England to warn you. When we arrived, we found things as you see them now, and we were trapped.”

“We’ve seen you since then,” said Jack. “Many, many times, in fact. How is that possible if you’ve been here all these years?”

“Where

is

here?” Bert asked. “‘Here’ wasn’t created until Hugo went through the door. And once that happened, everything forward changed.”

“I still don’t see how that would affect your return to England,” said John. “Our past hasn’t changed. Why did yours?”

“Jules and I travel via means that take us outside of time and space,” said Bert. “If we’d simply come back on one of the Dragon-ships, we’d never have noticed a difference. Jules has always kept his own counsel, though, and insisted that we needed to travel by his usual method, so we did.”

“You’ve mentioned time travel before, Bert,” John said, “but you’ve never gone into detail about how you really do it. It never came up as a factor in our roles as Caretakers until the problems with the Keep of Time, so I never asked about it.”

“And those problems are the very ones that caused this, aren’t they?” Bert said, his voice harsh. “If you’d paid closer attention to your responsibilities, then maybe we wouldn’t be here now.”

“That’s hardly fair, Bert,” Jack exclaimed. “You were there with us when Charles led us out of the Keep, before Mordred set it aflame.”

“Don’t bring

me

into this,” put in Chaz, “even if it’s the other me.”

“Jack’s right,” said John. “There were things you and Verne could have told us—about time travel, for example—that might have prevented this. But you always seemed to be playing your own cards close, Bert.”

“You weren’t ready yet,” the old man replied. “At least, in Jules’s estimation you weren’t. We had focused on you, John, as the one with the most potential to learn about the intricacies of time as well as space. But then we realized it might be Jack who possessed the greater capacity. We were wrong on both counts, it seems. No offense.”

“I can’t be offended,” Jack said, “when I don’t even understand what you’re talking about.”

“So you get my point,” said Bert. “Excellent. No, we realized it was Charles who had a bent for not only time travel, but also for interdimensionality. So we came back to England specifically to warn

him

.”

“Same with th’ Royal Animal Rescue Squad,” Uncas put in. “We were gived our instructions by th’ Prime Caretaker fourteen years ago.”

“That’s what I find intriguing,” said John. “Verne obviously knew more than he was telling you, Bert, to set a plan into motion that involved a rescue effort on the very day that these events would be set into motion in your own future.”

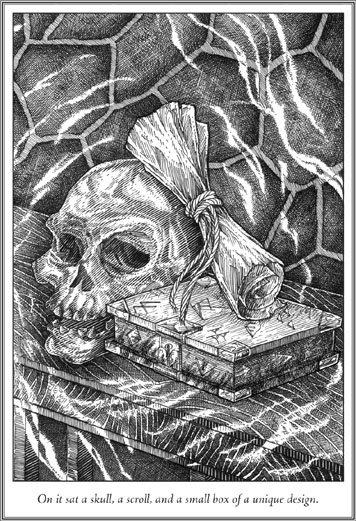

Bert stood and hobbled his way over to the mantel of the small tumbledown fireplace at the far side of the shack. On it sat a skull, a scroll, and a small box of a unique design.

Bert removed the box and set it in the center of his small table. The box wasn’t polished, but it was shiny with age; great, great age. The wood it was constructed of was pale, and there were cuneiform-like markings carved into the top and sides. Across the bottom were signs of scorching, as if it had been held to a flame. Jack reached out to lift the lid, but Bert slapped down his hand with the ash staff.

“Not so quickly, lad,” the old man said. “No telling what’ll come out of the Serendipity Box. Don’t want to let anything out that’s best kept in, for now.”

“What is a Serendipity Box?” Jack asked as he rubbed his knuckles. “Some sort of Pandora’s Kettle?”

“Not so dire as that,” said Bert. “It was your mentor, Stellan, who actually named it, John. What it was called before that, I can’t say.

“As the legend goes, it was given to Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, who passed it to his own son, Enos. Where it went after that is mostly lost to the mists of antiquity. But sometime in the past, it came into the possession of Jules Verne, and it was he who explained its workings to myself and Stellan.

“Adam explained to his son that the box could be used but once, and it was his choice alone when to do so. It would give whoever opened it whatever they most needed, and so the old Patriarch advised Seth that he should save it for a crisis, for a time of great peril, and only then open the box.”

“What did Seth use it for?” asked John, who still had not decided whether he even wanted to touch the Serendipity Box, much less open it. “I’ve never heard of it.”

“It was too long ago, and there are too many versions of the stories to know for sure,” Bert replied. “Some say that he was given a knife with which to avenge his brother, Abel. Others, that it contained three seeds from the Tree of Life, one of which he placed under Adam’s tongue when he died, the second of which he planted in a hollow at the center of the Earth, and the last of which he saved. One story even says that his wife, whom some called Idyl, sprang forth fully formed from the box, like Athena from the forehead of Zeus, and that she was not a Daughter of Eve at all.

“There is a fragment of scripture that claimed Enoch and Methuselah both used the box, and another that claimed it had been used by Moses to part the Red Sea. An entirely apocryphal account says that it was the Serendipity Box that held the thirty pieces of silver given to Judas Iscariot. But no historians I know of believed it.”

“Why is that?” asked John.

“Because,” said Bert, “according to the story, it was Jesus Christ himself who gave Judas the box.”

“Who had it between then and now?”

Bert shrugged, then rubbed absentmindedly at the stump of his right arm. “Jules and Stellan had some theories, and we read through the Histories at Paralon for clues, but apparently miracle boxes that are only good for a single use aren’t worth writing about.”

“Jules never said where he got it?”

“Here,” Bert said, rising and taking the skull from the mantel. He tossed the skull to John, who jumped up and caught it against his chest. “Ask him yourself. And let me know if he answers—I’ve been talking to him for years now, and he hasn’t said a word.”

The companions were speechless, except for Chaz, who watched with mild interest. “Kept it, did you, old-timer?” he said blithely as he walked to the window to pull back the curtain and peer outside. “I suppose the king wouldn’t notice one more or less in his tower walls.”