The Indigo King (11 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

“Wait now,” said Jack. “I’ve heard of that. It means ‘Infinite Beginning,’ does it not?”

“Not precisely,” said Anaximander. “More ‘Infinite Perpetuity.’ There is no beginning or ending, but merely an endlessly repeating process of beginnings

and

endings. Thus, an infinity of all things in space … and time.”

Jack nearly spit out his wine.

“Amazing,” said John, and translated for Chaz. “That’s a rather all-encompassing subject.”

“Indeed,” the teacher said. “Presently I am working on a new theory, which I call ‘multiple worlds.’ Essentially, I believe that our own world is but one of an infinite number that may appear and disappear at any given moment. Some find solidity and remain, while others flounder and disappear.”

Jack raised an intrigued eyebrow and looked at John. What Anaximander was describing was the very time paradox that Hugo Dyson had caused: The world they knew had vanished and been replaced by the Albion of the Winter King.

They both had the same thought: Was this Greek scholar in some way involved in what had taken place, or was his theory merely another coincidence?

A few more hours of discussion with Anaximander confirmed the answers to many of the questions that John and Jack had wondered about. The city was Miletus, on the Ionian coast of what they knew as Turkey. And as close as they could estimate from their fellow scholar’s calculations, the date was sometime around 580 BC.

The companions held off discussing the specifics of how and when they’d come to be in Miletus until their host had excused himself to fetch some more refreshments.

“Twenty-five hundred years!” Jack exclaimed, slumping back in his chair, “and then some. What was Verne thinking? What can we possibly solve by going back this far?”

“Remember what Bert said,” John reminded him. “Whatever it was that Hugo caused to happen in the past—uh, future—well, whenever he went—was anticipated by Verne. And we know who our adversary is. I think before we can do anything about Hugo, we’ve got to defeat Mordred, just like the prophecy said.”

“We already did that,” Jack huffed. “What if it was

that

defeat the prophecy referred to?”

John shook his head. “But we didn’t. Not in this timeline, remember? That would have happened after Hugo went through the door.”

“Drat,” Jack said. “I keep forgetting.”

Anaximander came back into the courtyard accompanied by a young man who appeared to be a student of his, given the way he responded to the older man’s instructions—not with abject obedience like a servant, but more deferentially than a son or nephew would have done.

“Come, Pythagoras,” Anaximander said, indicating the low table adjacent to John. “Just set the tray here. That will be fine.”

The boy deftly set the tray, laden as it was with bread, cheese, and grapes, on the table and then left.

“I see I’ve allowed the teacher in me to supplant the good host,” Anaximander commented, moving to the center of the courtyard. “You didn’t come here to ask about my philosophies; you wanted to know about my student. I assumed it was because of the legend that has sprung up around the stories that have been told.”

“What stories?” asked Jack.

“You are familiar with our great storyteller Homer?” Anaximander asked. “He of the

Iliad

, and the

Odyssey

?”

“Of course.”

“Not long ago,” the philosopher went on, “a rumor began to spread throughout the land that the gods had allowed Homer to be reborn as a youth, to reawaken the Greek people’s belief in wonder and mystery. From town to town and city to city, stories were being told in exchange for room and board. Stories the like of which have not been heard for centuries.

“Great, adventurous tales of fantastic creatures—centaurs and Cyclopes; talking pigs, beautiful sirens, and many, many more. And among these tales were scattered references to the place where they all were supposed to have happened—the Archipelago.”

John and Jack couldn’t resist the impulse to sit up straighter at this. “Your reborn Homer,” John said, “has he actually been to the Archipelago?”

“Better than that, if the stories are to be believed as truth, and not fabrication,” Anaximander replied. “They were

born

there.”

“I beg your pardon,” said Jack. “Did you say ‘they’?”

Anaximander merely smiled and rose to his feet. He crossed the courtyard and disappeared through one of the doors. The companions heard a muffled exchange of voices, and a moment later the philosopher reappeared, this time accompanied by two young men.

The first was not so much handsome as striking, which came across mostly through the intensity of his eyes. He was swarthy, muscular, and very, very confident.

The second young man was practically identical to the first. He was only negligibly shorter, and a bit more stocky. His complexion was slightly more pale, as if he spent more time indoors than his brother. But it was evident, John realized, that these were not only brothers, but twins.

“Gentle scholars,” said Anaximander, “may I introduce my two prize students—Myrddyn and Madoc.”

* * *

Chaz squinted and peered at the twins as if he’d been conked on the head and couldn’t quite register what he was seeing. “

Two

of ‘em?” he said to John. “

Two

Mordreds? I think we just went from th’ kettle directly inta th’ flames.”

John and Jack both stood to receive the visitors, but they were nearly as stunned as Chaz. Myrddyn and Madoc took each of their arms in greeting, and the companions realized that if pressed, they would not be able to say which of them had been the storyteller.

“It depends on the day,” Anaximander said in response to their unasked question. “That’s what has made the rumors of Homer’s return both credible and compelling. The ‘single’ storyteller has at times been reported in two cities on the same night, and has on occasion held an amphitheater full of citizens in thrall for several days with no apparent pause for sleep. These miracles are only possible, of course, because the single storyteller is, in fact, two.”

The twins took some fruit and goblets of wine from the table and settled into the chairs opposite the companions. As Myrddyn and Madoc recounted the events of the day with their teacher, John took the opportunity to examine them more closely. Myrddyn was the more outgoing of the two, and John was nearly certain that it was he whom they had seen in the amphitheater earlier. But then again, Madoc, while less forthcoming than his brother, nevertheless was compellingly familiar. Every gesture, every expression, bore some trace of the man they’d come seeking.

“This is impossible,” Jack whispered, leaning in close to John. “I can’t tell them apart. If they traded chairs, I might not even lose the thread of the conversation.”

“I know what you mean,” John whispered back. “Verne never mentioned this particular problem.”

“You do realize,” Myrddyn said, addressing the companions, “that our teacher is very protective of us and rarely speaks of our secret with anyone.”

“You mean your names?” asked Jack.

A flash of something indescribable crossed the young man’s eyes. “I meant the secret that we were born not here, in this world, but in the Archipelago.”

“Almost no one in the Greek empire knows of its existence,” said Madoc. “There are legends and stories, of course, but few who know the reality of it, as you seem to.”

“We’ve been there often,” Jack said before John could stop him, “and have many friends among its peoples.”

“Really?” Myrddyn said, leaning forward. “Such as who?”

John groaned inwardly, as did Jack, albeit a moment too late. He’d forgotten—they were centuries removed from the time that they knew, and their own journeys in the Archipelago of Dreams. Nemo was not yet born, or Tummeler, or Charys the centaur, or …

“Ordo Maas,” John said suddenly. “We are friends of Ordo Maas.”

The only reaction from the young men was a polite stare. The name meant nothing to them.

“Deucalion,” put in Jack. “He is also known as Deucalion.”

This brought about an entirely different reaction: Surprise and delight—and was that an expression of triumph John saw?—registered on Myrddyn and Madoc’s faces, and even Anaximander’s eyes widened in astonishment.

“The Master of Ships?” he said, his voice cracking. “Surely you jest with us.”

“Not at all,” John replied. “Do you know him?”

“Indirectly,” said Myrddyn. “He is our—mine and Madoc’s—direct ancestor.”

John and Jack looked at each other, bewildered. This was an unexpected complication. If one of these young men was indeed destined to become Mordred, that meant their greatest enemy was actually a blood relative of one of their strongest allies. But surely Deucalion would have known of this connection, wouldn’t he?

“How direct?” Jack asked slowly. “What

is

your exact lineage, if I may ask?”

Myrddyn nodded genially. “Of course. That is, in fact, what we have come here to discuss. Our ancestry is tied to both this world and the Archipelago.

“Deucalion, the son of Prometheus, was our ancestor six generations removed from our father, who went on a great voyage through the Archipelago in a ship given to him by

his

father. Near the end of his voyage, when all his companions had perished, his ship ran aground on an island where he spent seven years, before finally leaving in a small craft he built in secret.

“He left behind the ship of his father, Laertes; our mother, Calypso; and myself and Madoc, his sons.”

John was speechless, as was Jack. Only Chaz, who was barely following the conversation, remained unaffected. “What is it?” he asked John. “What did he just say?”

“Calypso, Laertes …,” John said to Jack. “Is it possible … ?”

Myrddyn smiled. “We were born in the Archipelago, but we have always known our destiny would lie here, in the land of our father—Odysseus.”

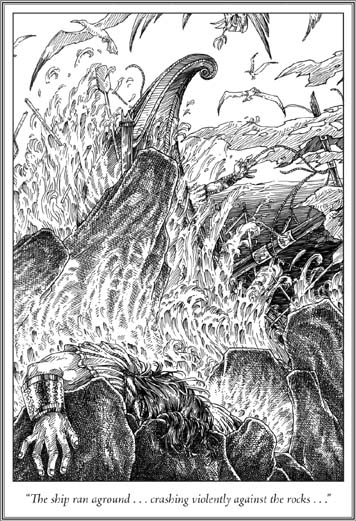

The Shipwreck

Nearly a year ago I was sailing with a small crew on a diplomatic mission to establish a colony at Apollonia,” Anaximander began, “when we lost our way and fell far off course. We were caught up in a terrible wind and found ourselves run aground on an island that seemed divided in half by a great line of storms.”

“Like Avalon,” Jack murmured. “Interesting.”

“While we repaired our own vessel,” the philosopher continued, “we saw another ship being tossed about by the waves, nearly to its destruction.

“The ship ran aground on the coast, crashing violently against the rocks, and I was the first to come to the wreckage. It was still being battered by the surf, but the two passengers aboard had been thrown clear. Before they could drown, I pulled the two of them from the water and brought them here.”

“Is it still there?” John asked. “The ship? Can you take us to the wreck?”

Anaximander shook his head. “The island is too far to travel to safely and quickly, and even were we to go, the ship isn’t there any longer anyway.

“As they recovered from their injuries, they both cried out for the ship in their fever dreams,” he explained, “concerned for the safety of their father’s vessel. But when I went back with several men to help me pull it aground, it was gone. An old fisherman who appeared near the rocks at the shore claimed to have seen it pulled back out to sea by seven scarlet and silver cranes.”

John looked at Jack. He recognized the description of the scarlet and silver cranes—the sons of Ordo Maas.

“After my duties at Apollonia were discharged,” Anaximander went on, “I offered to bring them here to become my students. But it turned out that I became their student as well—for they have told me many extraordinary things. Things unexpected from men of such youth.”

“And many tales of the Archipelago, I’d imagine,” said John.

“Yes.” The philosopher nodded. “Especially those.”

“Why are you sharing all of this with us?” asked Jack. “If you are from the Archipelago, the sons of Odysseus himself even, what can we possibly tell you about it that you don’t already know?”

Madoc leaned forward, eyes glittering. “You can tell us the most important thing,” he said, his face flushed and earnest. “You can tell us how to go

back

.”

At once, John and Jack remembered just

when

they were in history. There

were

no Dragonships yet. Ordo Maas had not yet built them. His own vessel, the great ark, had only gotten through the Frontier because it carried the Flame of Prometheus, the mark of divinity. And so the only other passages between worlds, like the journey of Odysseus, and Myrddyn and Madoc’s voyage back, were achieved through pure chance.

“We waited a long time to be able to come here, to the land of our father,” Myrddyn said, giving his brother an oddly disapproving look, “but we would like to be able to return home, to the island of our birth. And we would be willing to pay a great price to any man who might assist us in doing so.”

During the course of the discussion, Chaz had begun to pick up enough of the language to at least follow the thread of what was being discussed, and he brightened visibly when he realized there was an exchange of value being proposed.

John translated the words Chaz had missed as the others waited patiently.

“That’s an easy answer,” Chaz said when John was done. “We should just figure out a way t’ get that Dragonship of yours through the portal, and let

it

take them where they want t’ go.”

Jack slapped his head in dismay. Chaz had just blurted out several things they’d planned to keep to themselves—the ship, the portal … They were lucky that he’d spoken in English, so the philosopher and his students wouldn’t know what had been said.

John and Jack were so focused on Chaz at that moment that they did not see the shadow of fear that passed over the twins’ faces at the mention of the word “dragon.” But the philosopher did see.

Before John and Jack had time to respond further to Chaz, Anaximander pointedly cleared his throat, and Myrddyn and Madoc rose to their feet. “You must forgive us,” Myrddyn said, bowing. “We have enjoyed this meeting a great deal, but we have some responsibilities to attend to. May we continue this discourse in a short while? Perhaps in the morning?”

“Of course,” John said, also rising. “We have much more to discuss, I think. But please be aware,” he added with a glance at Jack and Chaz, “that we are merely passing through and cannot stay past tomorrow afternoon.”

While Anaximander saw the two young men out, John and Jack had an opportunity to quickly relate to Chaz everything else that had been said.

“It’s all beyond me,” he said, shrugging. “I don’t know what any of that whose-father-sailed-what-ship stuff has t’ do with our job.”

“It helps us understand what’s at stake,” John told him, “and gives us clues to figure out what to do.”

Chaz took on a disdainful expression. “Easy-peasy,” he said. “We go back to Sanctuary and try both names—Myrddyn and Madoc—on th’ Winter King. Whichever one works, well, that’ll Bind him, right?”

“I don’t think it’ll be as easy as all that,” John replied. “Not when there may be a blood rite, and the speaking of the Binding itself—if we can find someone who’s able. It’s too much time to risk on fifty-fifty odds.”

“So we have to find out for certain which of them will become a tyrannical despot in the future,” Jack was saying as Anaximander returned to the courtyard. “Great.”

“Hey,” said Chaz, “how do I ask where the, uh, facilities are?”

“Facilities for what?” asked John.

“I have t’ pee.”

“Oh,” John said. He repeated the query in Greek to Anaximander, who seemed not to understand.

“He wants to go to the room where we make water?” the philosopher asked. “We don’t have a ‘room’ for that, but we do have pots in some of the larger buildings. I have one myself, if your friend would like to make use of it.”

John translated, and Chaz screwed up his face in disgust. “I’d just as soon not be sharing a chamber pot, t’anks,” he said. “Isn’t there a nice, clean hollow log somewheres?”

Again John translated, and Anaximander answered.

“He says most everyone just uses the street,” John said apologetically. “Welcome to ancient Greece.”

Grumbling, Chaz exited the same way the twins had left, and Anaximander moved over to take his chair.

“What do you think of my students?” the philosopher said, sitting between John and Jack. “Impressive, are they not?”

“Do you believe them?” Jack asked. “Do you really think they are the sons of Odysseus?”

“It’s impossible to know for certain,” Anaximander admitted, “but their tale rings true. We know from our own histories that Odysseus had children with both the witch Circe and the nymph Calypso, but little was known of what became of them, until last year, when I found Myrddyn and Madoc and learned of their parentage. They know more about the details of Odysseus’s journeys than any scholar, more than has been recorded in any history. And so I must give credence to their claims, however outrageous they might seem.”

“I don’t know what we can do to help,” John said plaintively. “We’ve told you all we can.”

“Ah, but I think this is not the case,” Anaximander replied. “No—don’t be alarmed. I’m not irritated that you have chosen to keep things to yourselves—especially in front of an unknown audience. Am I correct?”

Their uncomfortable silence told him he was.

“Well then,” the philosopher said, “it seems I must make the first gesture of trust.” He stood and walked to the far side of the courtyard, motioning for them to follow. “I have been developing a new science, based on the idea that there are places in the world that cannot be traveled to except by following a very specific and detailed route,” he said as he opened a large, stout door.

“The place where Myrddyn and Madoc were born, the Archipelago, is of our world, and not, all at once. And so I reasoned that the only way to discover the location of an unknown place would be to create a means to represent all the places that

are

known.” Anaximander lit one of the lamps in the darkened room, and it suddenly blazed with light. “I call it a

map

.”

The two Caretakers stepped into the room and looked around in mute astonishment. Maps. The entire chamber was filled with maps. There were also globes, whole and in pieces, and crude sextants, and even a construction that resembled the solar system, hanging from a thin wire in a corner of the room.

“Cartography,” John said, his voice trembling with the realization, as he gripped Jack by the shoulder. “Anaximander is teaching them to make maps.”

“Better than that,” Jack replied. He was also shaking. “He’s making maps to unknown lands. To lost places.”

“Are … are you the Cartographer?” John asked.

Anaximander bowed deeply. “I am what I am,” he said simply. “Now, let us speak of the Archipelago, shall we?”

The problem with trying to relieve oneself in ancient Greece, Chaz decided, was that everywhere he went, there was some kind of statue or carving or bas-relief with a face on it—which meant that every time he stopped to pee, something was watching him.

And it was flat-out impossible to loosen one’s bladder when one was being watched.

Finally he managed to find a decent spot in between a tall, stout olive tree and a great cistern. The shadow underneath afforded just enough privacy to do what needed doing, as long as not too many people passed by.

Chaz had unbuckled his trousers and was just preparing to relax and let loose the torrent, when he heard familiar voices. He pulled up his pants and leaned back to peer around the cistern.

It was Myrddyn and Madoc. They were at the other end of the alley, having a heated if hushed exchange.

Chaz moved closer to listen. He still could not understand most of what they were saying—but he could

remember

. And he was catching just enough—words like “ship” and “dragon”—that he knew it might be important to remember it all.

“And what happens if we’re found out?” Madoc was saying. “They claim to know Deucalion—that means they could discover the truth: that we were exiled from the Archipelago.”

“No one needs to know that!” Myrddyn hissed, grabbing his twin by the collar. “Least of all Anaximander! Only Deucalion, the Pandora, and the Dragons themselves know what really took place before we came here. And that’s the way it will stay until we can return!

“No,” he said, finally releasing his grip on Madoc’s tunic, “we’ll use them for whatever information we can glean, and then we’ll dispose of them, as we have the others. He’s already prepared the wine, as he has before.”

“You know I’m uncomfortable with that, Myrddyn,” Madoc said, his voice low. “We could have trusted some of them, I think.”

Myrddyn shook his head. “It’s too great a risk,” he said blithely. “The knowledge of the Archipelago is rare, and it must remain so. The fewer who know anything of it, or of us and our real reasons for returning, the better. Do you want to get father’s ship back or not?”

After a moment, Madoc nodded, still reluctant. Then together the brothers turned and walked back toward the amphitheater.

When he was certain they had gone, Chaz emerged from the shadow of the cistern where he had been watching them and stood in the alleyway, breathing heavily and trying to reason out what he believed he had heard.

For a long moment, Chaz considered his options, looking hard in the direction of the philosopher’s house. Then, abruptly, he spun about and began walking toward the amphitheater and the plaza … and the portal back to Sanctuary.

Of any scholars of the ancient world who made maps, only Anaximander had conceived of one depicting the entire world.

The maps he showed to John and Jack were crude by their standards, but revolutionary for the philosopher’s time. And they were good enough for a beginning. Some, John suspected, might even be

in

the

Imaginarium Geographica

.

Anaximander had already sussed out the fact that John and Jack were versed in the reading and function of maps, and so he proposed that they help him in indexing the ones he and the twins had already made, to see if they could add details to their growing store of knowledge about the Archipelago.

With unspoken reservations, and keeping their objective in mind, the two Caretakers agreed—but while they worked, the same concern played out in both of their heads.

To return home, Myrddyn and Madoc needed two things: first, something to guide them—the maps, which would eventually form the basis for the

Imaginarium Geographica

; and second, a vessel touched by divinity, as Odysseus’s ship had been once, able to make the journey and traverse the Frontier.

They could not help with those things, but they could provide a lot of information about the Archipelago itself. Too much, in fact. In their own time, when they’d first met each other, it had been Mordred’s objective to seize the

Geographica

in order to conquer the Archipelago. And that was after he’d only been back in the Archipelago for twenty years.