The Indigo King (12 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

Giving him, whichever of the twins he was, the means to return twenty-five centuries earlier could devastate the world more than Hugo’s mishap had. So they would organize, but not contribute to, the philosopher’s work.

A not-too-casual mention by Anaximander that he was fascinated by the concept of time was enough of a prompt for John to pull out his gold pocket watch and proudly show it off. He explained the mechanism and workings of the watch, but much to Jack’s amusement and Anaximander’s confusion, the watch, as usual, didn’t work.

“So it’s like my gnomon,” the philosopher concluded. “A stationary vertical rod set on a horizontal plane. But,” he added, still puzzled, “what is the transparent dome for? It seems it would work better if the rods were more vertically inclined.”

“Oh never mind,” John said, setting the watch on the table and glaring at it. “It’s really best as a paperweight.”

“It’s an excellent paperweight,” said Anaximander.

Twice as they worked, the philosopher’s younger student, Pythagoras, brought food and drink. The second time, Anaximander left the companions for a moment to give more instructions to the boy.

“John,” whispered Jack, moving around the table so Anaximander would not overhear them, “Chaz went out a

long

time ago. I don’t think he’s coming ba—”

“

I know

,” John whispered back, his voice bitter. “I know, Jack. We still have time. Let’s just do what we can here, and hope …”

John let the sentence trail off without finishing and resumed work on the maps.

Chaz made it to within twenty feet of the portal, where he paced through the entire night. He couldn’t decide whether to go through or pee, so he merely paced, and argued with himself.

He had paced through the night and into morning before the pressure became too bad, and he finally was forced to relieve himself on the broad wall next to the plaza entrance.

“Aw, geez, Mister Chaz,” came a small voice from behind him. “D’you hafta do that out here, where everyone can see? What, were you raised in a barn?”

Startled, Chaz turned around to see who had spoken. It was Fred, tapping his foot and trying not to watch as the human splashed urine all across the wall.

“Fred!” Chaz exclaimed, with a chagrined, half-embarrassed look. “Have you been watching me pee?”

“No,” replied Fred, “we’ve been watching you pace. We thought you must have been sent back t’ stand guard. You only just

started

t’ pee.”

Chaz looked around worriedly. It might be a strange land, but he suspected a talking badger wouldn’t go unnoticed for very long. “What are you doing here? Why did y’ come through th’ portal?”

The small mammal held up an hourglass. “Th’ time limit!” he exclaimed. “It’s almost up. You and Scowler John and Scowler Jack must return, right now!”

The badger was right. There was only a thin layer of sand left inside the upper globe of the hourglass. Could it really have been twenty-four hours already? Chaz wondered. Regardless, he wasn’t about to be trapped in a place where he couldn’t speak or understand the language without getting a headache.

“Okay,” he said, heading for the portal.

“Wait!” Fred cried, pulling on the man’s shirt. “What about Scowler Jack and Scowler John?”

Chaz sighed and rolled his eyes, then looked from the portal to Fred, and back again.

“This way,” he said finally, fastening up the buckle on his trousers. “We’ll have to hurry.”

By midday Anaximander’s entire map room was sorted and indexed, John and Jack were completely exhausted, and they were not one inch closer to discovering which of the twins was destined to become Mordred.

“This would have been easier if he already had the hook,” Jack grumbled, yawning.

“At the Ring of Power, when Artus and I were fighting Mordred, he said he was nearly as old as Ordo Maas,” John said, rubbing his chin. “I thought it was just bluff and bluster at the time, but the flood that took Ordo Maas to the Archipelago happened at the beginning of the Bronze Age, and the timing is right for the genealogy to work.”

“That’s still almost a thousand years earlier than we’ve come,” Jack countered. “But I suppose it isn’t inconceivable that they both lived a long time, maybe centuries, in the Archipelago before coming here.”

Before they could continue the discussion, the door burst open and Chaz and Fred rushed inside.

“Where the

hell

have you been?” Jack exclaimed. “We thought you—”

“Wasn’t coming back?” Chaz shot back. “Hah. Fat chance of that, eh, Fred?”

The little badger looked up, surprised, then gave Chaz a thumbs-up and a grin.

“Where have you—,” John started to say.

“No time,” Chaz cut in. “You have to hear what I overheard last night, an’ then”—he pointed to Fred’s hourglass—“we got t’ go.”

Chaz quickly recounted the whole argument he’d witnessed between Myrddyn and Madoc, repeating the strange Greek words as best he could. When he was finished, Jack snorted.

“You don’t

speak

ancient Greek, Chaz,” he said mockingly. “I think you’re making things up out of your head.”

“I’m picking up more than you know,” Chaz retorted. “An’ I didn’t need t’ understand it all t’

remember

it.”

“I don’t know, Chaz.” John said doubtfully. “It all fits, but Jack does have a point. We don’t know you heard what you think you heard.”

“If it wasn’t me,” Chaz asked, glancing down at Fred, “if it was

him

, th’ other me, would you trust me?”

“You mean Charles?” said Jack. “Of course.”

“Then trust him,” Chaz said to John. “Somewhere I’m him, you say. Well, last night he was me. Trust him. I mean, me. Trust me, John.”

John looked questioningly at each of the others in turn. Fred nodded immediately, and finally, more reluctantly, so did Jack.

“They want to get Odysseus’s ship back, do they?” John began. “He got it from his father, Laertes, who was one of the original Argonauts,” he said, rubbing his chin. “Do you suppose the ship Anaximander saw was … ?”

“The

Red Dragon

!” Jack said excitedly. “They came here from the Archipelago in the

Red Dragon

!”

“Mmm, no,” said Chaz. “They called it something else … the ‘Aragorn’ or some such.”

“The

Argo

,” said John. “Jason’s ship. That means that Ordo Maas, or at least his sons, had gone to the island to take the wreck of the

Argo

back into the Archipelago, in order to transform it into the first of the Dragonships—the

Red Dragon

.”

“Exiled, eh?” said Jack. “I bet that’s the reason they were shipwrecked, and why the ship was taken back once they were here.”

“One or t’ other has t’ be Mordred,” said Chaz, “but if the other is anything like th’ first, then wouldn’t he still be somewhere in the future, too?”

Jack’s jaw dropped. “That’s brilliant, Chaz.”

“We already

have

met both of them!” John said. “One of them is the Winter King—and his twin is the Cartographer of Lost Places! It’s the only answer that makes any sense!”

“But which is which?” said Jack.

Fred tugged on Chaz’s shirt and tapped the nearly empty hourglass.

“The twenty-four hours!” Chaz said. “It’s almost up! We have to go, else we’ll be trapped here!”

“You’ve labored long and hard,” a voice said from the doorway. “I’ve brought you more refreshments.”

Anaximander entered carrying a tray with a flagon of wine and two goblets. He started when he saw Chaz, and he studiously ignored Fred. “I’m sorry,” the philosopher said, awkwardly balancing the tray. “I’ll fetch another goblet.”

“Where’s Pythagoras?” Jack asked. “Doesn’t he usually fetch the wine?”

“I, er, sent him home,” Anaximander said. “I thought as a show of gratitude I would serve you the morning wine myself.”

“No!” yelled Fred, leaping up to the table and knocking the tray from the philosopher’s hands.

“Fred!” Jack began, but he stopped short as they all looked down at the spilled wine, which sizzled and bubbled on the stone floor.

“Animal instincts,” said Fred, “and a good nose.”

“Right,” Chaz said. His left fist snapped up, and he struck Anaximander brutally in the jaw. The philosopher went down hard, falling in a sprawl at the man’s feet. “Y’ unnerstand

that

?”

The truth of what was happening slowly sank into John and Jack as Chaz and Fred headed out the door. “You didn’t make any of these maps, did you, Anaximander? One of your students did.”

“The desire is there, but I have not the skill,” the philosopher admitted, teeth clenched. “It was that boy, that

child

.… He had such a hand, and such a clear mind for detail.… I had saved his life, after all. Wasn’t I entitled to benefit from that? Wasn’t I?”

Jack cursed in English, then switched back to Greek. “We don’t care about that!” he said harshly. “We just want to know which of them it was!”

“Jack! John!” Chaz shouted from the courtyard. “Now!”

“Anaximander! Please!” John called as he backed out of the map room. “We have to know! We need to know! Tell us, please!

“Who is the Cartographer?”

But no answer was forthcoming. John and Jack raced out of the philosopher’s home as he collapsed in a wreck of tears and regret.

Chaz, with Fred trailing behind, already had a good lead, and the streets of Miletus were broad and uncrowded. There would be no real gathering in this part of the town for another hour or two, John thought wryly. Not until the storyteller, whichever twin it was today, made his appearance in the amphitheater.

To his credit, Chaz had slackened his pace just slightly enough to allow the badger to keep up, so John and Jack had nearly caught up to them by the time the thief and the badger had entered the portal.

Jack raced through next, hardly pausing in the apparent act of running into a marble wall. John was close on his heels and cut the timing tightly enough to see the edges of the projection beginning to close in and lose their shape.

He passed through the gossamer layers and turned around for one final look at Miletus—and saw Myrddyn and Madoc dash from an alleyway and into the plaza.

In seconds the twin sons of Odysseus had spotted the unusual nature of the wall where the companions had vanished, and they moved quickly to follow, swords drawn.

But it was too late. The projection began to fade as the slide was burned dry by the incandescent bulb in the Lanterna Magica, and in a moment, the portal had closed in front of them. Ancient Greece was history.

“Curse it all,” said John. “I’ve forgotten my watch.”

The Grail

The harsh white light of the Lanterna Magica cast deep shadows behind John, Jack, and Chaz as they stood, reeling from the chase, and realized they were once again safe in the projection room on Noble’s Isle.

“The giants!” Jack exclaimed, looking around in trepidation. “Are the giants still outside?”

Reynard moved to him, making soothing gestures with his paws. “No need to fear. They retreated when they realized you were no longer here. But,” he added, almost apologetic, “they may yet return. Were you successful in your mission?”

At that both Jack and Chaz looked at John, who took a deep breath. “Well, yes and no,” he admitted. “I think we found the answer we were looking for—Mordred’s true name—or at least, we’ve narrowed it down. But we still don’t know how to use it against him.”

Sitting to rest, the three men took turns recounting the events of the last day to Fred and Uncas, as Reynard ordered in food and drink.

Chaz hungrily tucked into the pile of cheese and bread that had been brought in by three ferrets. “Truth t’ tell, I’m more sleepy

than anything,” he said through a mouthful of food, “but this may be the best sandwich I’ve ever had.”

Reynard bowed in gratitude and began to pour a cup of wine. Chaz stopped him, covering the cup with his hand. “If it’s all th’ same t’ you,” he said, looking at the others, “I’d just as soon stick t’ water or ale after this trip.”

“Agreed,” said Jack, shuddering at the thought of how close he’d come to drinking the poisoned wine. “Thanks for the save, Fred.”

The little mammal would have blushed if he could. As it was, he beamed happily and chewed a crust of bread Chaz had handed him.

“One thing’s certain,” John said. “We went into that completely unprepared. We can’t do so a second time.”

“To be fair,” said Uncas, “there

were

giants at the door yesterday.”

Chaz nodded grimly. “An’ they could be lurkin’ about even now—so we’d best get prepared and decide what t’ do right.”

“Is it me,” Reynard whispered to John, “or didst his countenance change during your journey into the projection?”

“His appearance?”

The fox shook his head. “Countenance. His … appearance beneath what we see with our eyes.”

“Mmm, perhaps,” John mused, looking at his reluctant companion. “Maybe it has, at that.”

“So,” Uncas began, “how do we prepare you better for the next trip, other than giving you the hourglass this time around?”

“Yes,” said John. “You saved us there, too, it seems. As to being better prepared, I don’t think there is anything further that we

can

do. We simply don’t have enough information to work with.”

“Maybe we do,” Jack said, a look of excitement on his face. “Remember? The warning! The warning in the book that was sent to Charles!”

John swore under his breath. “I’d completely forgotten about it,” he admitted, “not that it would have done us any good where Verne sent us.”

“What do you mean?” asked Jack. “Why not?”

“At its earliest, the representation of the Grail wouldn’t have had any meaning at all until a few decades after the crucifixion of Christ. And we already know that Hugo was sent back several centuries later than that. So I don’t see how his warning is relevant to Verne’s mission.”

“But it

is

relevant, don’t you see, John?” Jack exclaimed. “Hugo gave us the answer in his message! It’s the Cartographer! Mordred’s twin! His own brother

would

be capable of the Binding!”

John’s brow furrowed in concentration as he considered Jack’s idea. It might in fact be possible—he was unclear as to the rules that regulated the power behind the Summonings and the Bindings, except that they had to be spoken by someone of royal birth. Artus was able to do it, as had Arthur, generations before him. Aven’s son, Stephen, could have done it as well. And they already knew Mordred was capable of doing a Binding—so the same

might

be true of his brother.

“We know the Cartographer’s existence predates Arthur’s rule,” John reasoned, “and we’d already suspected that Mordred did too. And remember—back on Terminus, Mordred did say that he and Artus shared the same blood. So somehow the authority to speak Bindings and Summonings comes from somewhere beyond even Mordred.”

“Fair enough,” said Jack. “That means his twin—the Cartographer—would possess the same ability. Hugo’s note mentioned the Cartographer, and Verne told us we needed to discover Mordred’s true name in order to defeat him. We can’t do that here,” he said, waving his arms to indicate Albion as a whole. “There are no other kings able to do to

him

what he can do to

us

. And I don’t think the authority of the Caretakers can overpower the authority of the king.”

“Mebbe that’s what this ‘Verne’ meant f’r us t’ do,” said Chaz, who was sitting against the wall, dozing, but still listening. “Mebbe it’s up t’ us t’ turn one of the brothers against the other.”

“That’s what it comes down to, doesn’t it?” Jack asked. “We have to convince whichever one is the Cartographer that his brother will eventually turn rotten, and that the only way to prevent it is to Bind him.”

“But for how long?” wondered John. “Binding can’t really be permanent, unless …”

Only Chaz and Reynard didn’t understand John’s unspoken thought, which the others knew as part of their own history: The only way to defeat the Winter King was to kill him. And even that had proven to be problematic.

“Y’r still forgetting one thing,” said Chaz. “He in’t the Cartographer yet. And

both

of ’em were thrown out of the Archipelago, remember? I heard ’em say it. And they were both in on th’ plan t’ kill

us

, if you recall. When they was chasin’ us out of Miletus, they

both

had drawn swords. That says poison t’ me. Both of ‘em. They be poison.”

“Isn’t the Cartographer your friend?” asked Uncas. “Back where we came from?”

John shook his head slowly. “I don’t think the Cartographer is anyone’s friend, to be honest,” he said. “We went to him when we had to, and no more. And he gave us what he needed to, and no more. It wasn’t so much a friendship as it was cooperation between interested parties.”

“Isn’t that what you’re seeking now?” asked Reynard, who had been listening from the back of the room all the while. “Not his friendship, but his cooperation?”

“Yes,” Jack replied, “but we have less to argue with here. Back in our world, he was a virtual prisoner, locked in the Keep of Time, behind the door that bore the mark of the king.”

“Mordred’s mark?” asked Chaz.

“Arthur’s mark,” said Jack. “Different king, but the Cartographer was just as trapped.”

“What for?” asked Chaz. “What did

he

do t’ piss someone off?”

John shrugged. “No one’s ever said. I’m not sure if anyone really knows. None of the Histories ever mentioned it, that’s for certain.”

“Mayhap we should consult th’ Little Whatsit,” offered Uncas. “There be lots of unique knowledge there that even some scowlers may not know.”

“Thank you, Uncas,” John said gently, “but this is bigger than just healing blisters or making magic darts.” He sat in the chair next to the badger and looked at the projector. “I wonder if we shouldn’t turn it on and have a look at the next slide? That way we can equip ourselves ahead of time for wherever and whenever it lands us.”

“Do we really want to do that?” asked Jack. “We can’t afford to use up the hours. Once we turn it on, we have twenty-four hours maximum before the slide burns out. And we’re going to need every second to convince the Cartographer to join us against his brother.”

“You’re probably right,” said John. “We became acclimated pretty quickly in Miletus, and Chaz was useful in helping us blend in. Perhaps this really will just be a leap of faith.”

John’s sentiment was punctuated by a loud boom from outside and a faint tremor which shook the room.

“Oh, no,” Jack groaned, slapping his forehead. “Here we go again.”

“Wait,” Reynard said, rushing from the room. “Let me see for certain.”

Any doubt they felt as to what had made the noise was dispelled a moment later when the voice of the giant filtered through the walls of the building. “

Jaaackk,

” it said, menacing and persuasive all at once, “

Jaack … wee have a preeesent for youuu

.…”

There was a crashing somewhere outside the house, and a cacophony of animal noises, then silence.

“They’re being a bit more restrained than the last time,” John observed. “That can’t be good.”

Chaz agreed. “They’s up t’ summat, for sure.”

A moment later the fox reentered the room.

“I have good news, and bad news, and worse news,” Reynard announced. He was trembling. Whatever had just transpired outside had rattled the fox to his core.

“What’s the good news?” Jack said.

“The giants will honor the king’s covenant with the Children of the Earth,” Reynard answered. “They will not cross our boundary and step onto Sanctuary.”

“Excellent!” Jack exclaimed. “We’ll be safe here, then.”

“Trapped, y’ mean,” Chaz said glumly. He looked at the fox. “They in’t going anywhere, is they?”

Reynard shook his head. “They are at the four points of the compass—one each at north, south, east, and west. They will not permit you and your fellows, or indeed, anyone else to leave Sanctuary while you are here.”

“I’m guessing that’s the bad news, then,” said John. “Should we dare ask what the worse news is?”

Reynard leaned back and motioned for the large jackrabbit that waited in the hall to come into the projection room. The animal was carrying a small burlap sack, tied with a ribbon and bearing a card. The rabbit set the bag on one of the chairs, then hopped quickly away.

John stepped forward and looked at the card. It read simply,

To complete the set

.

He frowned and undid the tie on the bag, which dropped open.

The badgers gasped and turned away, and Jack covered his eyes with his hands. Chaz reacted even more strongly, cursing and clenching his fists in anger. As for John, he simply closed his eyes and murmured a hasty prayer before retying the bag that held his old mentor’s head and setting it reverently in one corner of the room.

John turned to Reynard, wiping his eyes with the back of his hand. “There’s no more time to waste,” he said as boldly as he could manage. “Let’s see the second slide.”

* * *

The companions prepared for the second jaunt through the Lanterna Magica’s projections while trying to ignore the frequent taunts of the giants, and even more so the grisly present in the burlap bag.

John decided against including the hourglass in their supplies, making the argument that it could too easily be lost, broken, or upended. “No,” he said, “I think what happened before is really our ideal. Uncas and Fred will be our timekeepers. You’re both safe here on Sanctuary anyway, and you can come fetch us as the time grows short.”

“They were able to do that last time because I, ah, were passin’ by the portal,” said Chaz. “How will they find us this time around?”

“We’ll have to be aware of the time ourselves as best we can,” said John, “and try to keep a bearing on the position of the portal so we’ll be nearby.”

“Don’t worry, Scowler John,” Uncas stated with a salute. “Th’ Royal Animal Rescue Squad will not fail you.”

“I know you won’t, Uncas,” John said, resisting the urge to pat the badger on the head while he was being stately. “The son of Tummeler would never let us down.”

Uncas looked so proud at the compliment that John thought he might burst into tears. “Ready?” he said to Jack and Chaz.

Chaz yawned and nodded. “Enough, I guess.”

“Ready,” agreed Jack.

“All right,” John said, signaling Reynard. “Light it up.”

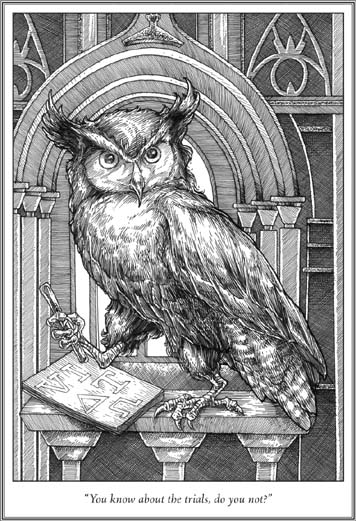

The fox pressed the switch that rotated the disc of slides, and the next image slid smoothly into view. John, Jack, and Chaz stepped aside to better get a view of the slide, and Uncas and Fred dutifully turned over the hourglass.

As before, the multiple layers that were projected on the wall gave everyone a slightly disoriented feeling. It took a few moments for their vision to adjust to the shifting perspectives, and then they could see what was on the slide.