The Indigo King (16 page)

Authors: James A. Owen

“Drat,” said Hugo. “I should have asked for his autograph.” He looked at the tent opening, then back at Hank. “Does he know about … ?” He pointed delicately.

“About me?” Hank exclaimed. “Where and when I’m really from? I doubt it. I made up a story when I first got here, which I’m pretty certain he saw right through. But I’ve been helpful to him, and loyal. So he doesn’t press the matter.”

“And you’re here at the behest of Sam Clemens?”

“His and that of his former apprentice, a Frenchman called Verne. Do you know him?”

Hugo shook his head. “Not personally.”

“Well,” Hank continued, “he’s the one who worked out a lot of the underlying principles behind time travel and zero points.”

“Uh, zero points?” asked Hugo.

“The points in history that allow travel, or at least communication, in the case of the lesser points. There was a good one about fourteen years before your prime time that I was able to use to send a message to Verne. I don’t know what it was that happened then, but it must have seemed like the end of the world.”

“One or the other,” Hugo said, “from what I’ve been told. So,” he continued earnestly, “this message you sent. Will it allow Verne to fix whatever it is that happened to me at Addison’s Walk?”

Hank shrugged. “I don’t know. When you showed up, I thought I’d better let someone know. Mistakes like that usually aren’t mistakes at all.”

“You think someone deliberately arranged for me to come here?” asked Hugo.

“I do, and what’s more,” Hank said, checking the silver watch, “so does Sam. You’re to stay here, at least for now.”

Hugo was aghast. “But why? Isn’t there some sort of … I don’t know, time machine they can use to whisk me back to Magdalen?”

Hank gave a wry chuckle and scratched his neck. “It doesn’t quite work that way. I’m still a novice, a foot soldier, if you will. But even I know you aren’t supposed to mess around with time by traipsing to and fro.”

“But you’re here,” Hugo protested. “Isn’t that meddling?”

“No,” said Hank. “I’m here in part because one of the Caretakers’ Histories said I was. So I was meant to be here. You weren’t.”

“But don’t you see,” Hugo declared, having suddenly realized something. “I was. I was meant to be here. Or else how do we explain the Grail book that I supposedly wrote in?”

Hank stared back at him, puzzled. “That

is

a good question,” he said, removing the silver watch again. “I’d better—”

Before he could finish speaking, the watch emitted a high-pitched squeal and began to spark, then smoke. Hank shook it, then held it to his ear. It had stopped ticking.

“That looks bad,” said Hugo.

Hank bit his lip, thinking, then replaced the watch in the secret pocket. “Come on,” he said, standing. “Let’s see where this goes. It’s high noon—the tournament is about to begin, and Merlin will be looking for me.”

Hank loaned Hugo a cloak and spare helmet, which they hoped would lend just enough camouflage to the professor’s appearance that he could move about more freely. It worked for the most part—although the elves kept pointing at him to get his attention, then making rude gestures.

“I’m starting to warm to the opportunity I’ve been given to have this adventure,” Hugo said dryly, “but if I never see another cursed elf, it’ll be too soon.”

The tournament was centered not at the great stone table, as Hugo assumed it would be, but around a field to the west of it. There a great tent had been erected facing a low hill, on which they could see a few crumbling walls that marked rough boundaries around a shallow depression.

The participants had assembled around the front of the tent, waiting for the announcement and a proclamation of the rules.

“Taliesin’s tent,” Hank murmured as they approached. “Hang back a bit, so we can watch. We don’t want to get too wrapped up in events. No telling what could happen if we get involved in something by accident.”

Hugo was more than willing to keep a comfortable distance. He’d realized with an alarming clarity that these knights assembled here were not the same as those he’d read about in the great medieval romances. These were warriors; battle-hardened and less likely to be chivalrous than they were to be actors in a play. What’s more, he wasn’t certain that all of those at the gathering were even human.

There was movement at the rear of Taliesin’s tent, and Hugo saw Merlin exit from a flap in the tent, and then walk around to the back of the hill. A few moments later he reappeared at the crest of the hill and strode down into the assemblage.

“What a show-off,” Hank whispered, scribbling in his notebook. “He was up there just so he could arrive last and appear to have come down to everyone else’s level.”

Merlin passed easily through the crowd, which parted to let him through. Apparently his reputation had preceded him. He took a position not far from the front of the tent and crossed his arms, waiting.

He didn’t have to wait long. The front of the tent opened and Taliesin appeared. He was tall, bearded, and graying at the temples. He wore a simple tunic, leather breeches, and tall leather boots. There were feathers in his hair, which was swept back and grew long, almost to his waist in back.

Taliesin carried a black staff carved with runes, which seemed to glow faintly, even in the daylight. He walked to the base of the hill, then turned to address the gathering.

“I am Taliesin, called the Lawgiver,” he began, his voice low but commanding in tone. “Hear my words, all ye who have been summoned.

“We have come here, to the place where once, long ago, the man called Camaalis earned for himself the mantle of king of Albion and ruled this land as his stewardship. Here he built his first castle, called after his name, and here he died and was forgotten.

“What was lost to history, and forgotten by men, is that he was to be the ruler of two worlds—both this land we know, and another, in the Unknown Region.”

“The Archipelago?” Hugo whispered.

“I think so,” Hank replied, writing. “This is very intriguing.”

Taliesin went on. “Others have ruled parts of these lands since, but never the whole, and never the lands beyond. Those who had appointed Camaalis withdrew the knowledge and the means, until another, one worthy to rule, could be chosen.

“If there is no authority to rule, no chosen leader acknowledged by all, only a group of ‘nobles’ willing to destroy the land in order to wrest control of it, then the lands beyond will also remain forever apart.

“This is why the tournament has been called. To reestablish the lineage of the authority to rule. The lineage that began with the gods of myth and passed through their heirs—the heroes of the Trojan War.

“Aeneas, one of the great heroes of antiquity, possessed a great sword. When the walls of Troy finally fell, his grandson, Brutus, smuggled it away from those who would use it to further their own ends.

“He sailed far away, taking with him the sword and those who had managed to escape from the marauding Greek armies. He came here, to the island called Myrddyn’s Precinct, where he founded a settlement called Troia Nova.”

“Troia Nova,” Hugo whispered. “New Troy, then … It eventually became Trinovantum, then Londinium, didn’t it?”

Hank didn’t hear the question. “Did he say Myrddyn’s Precinct?” he asked instead. “That’s rather ominous, don’t you think?”

“There was another hero of the Trojan war,” continued Taliesin, “called Odysseus, who had a bow that could not be drawn except by the true king. That promise and curse protected his homeland of Ithaka for generations. And the same promise and curse, passed down through the lineage of Aeneas, will protect those who would unite and rule the world—beginning here, in Myrddyn’s Precinct, at the place where Camaalis was buried.”

Taliesin moved aside, and for the first time Hugo and Hank could see what was in the depression on the hill.

It was a stone block, which bore the mark of the Greek letter

alpha

. It was, Hugo realized, the topmost stone of a crypt.

At Taliesin’s signal, several burly men moved forward, grasped the sides of the great stone block, and slowly moved it aside. Underneath, set into the hillside, was a stone box. One of the knights removed the topmost stone and set it aside.

There, lying in state, was a black sword in a scabbard, covered in the dust of the first great king of the land.

“Caliburn,” the Lawgiver proclaimed, pointing down at the crypt. “The sword of Aeneas.

“Whosoever is able to draw the sword from its sheath shall henceforth be the High King of all the lands that are. So say we all?”

The question was answered with a thundering shout, which only grew louder and louder as the seconds passed, until Hugo thought he would go deaf from the noise of it. Finally the whoops and hollers died down, and the Lawgiver Taliesin spoke once more.

“The Tournament of Champions is begun.”

The Stripling Warrior

Uncas, Fred, and Reynard

clustered around John, Jack, and Chaz as they stepped back through the projection.

“Is everything all right, Scowler John?” Uncas asked worriedly. “You’ve only been gone about ten hours.”

“Fine, Uncas,” John reassured him. “Reynard? Shut down the projection, quickly!”

The fox swiftly moved over to the Lanterna Magica and flipped the switch. Immediately the lamp went dark and the slide vanished from the wall, and with it the conflagration in the library.

“Thanks,” said Jack, sitting in a chair and slumping over the back. “I don’t think I could bear to watch.”

“I was more worried about Sanctuary,” John said, taking one of the other chairs. “If we could pass through, other things might be able to also. And it won’t be too long before the wall we came through is on fire itself.”

Only Chaz was still standing at the wall. He was touching his chest and arms, as if confirming his own solidity.

“Mister Chaz?” said Fred. “Are you all right?”

“Did we do it?” Chaz asked hesitantly. “Did we change the world?”

Fred looked at Uncas, who looked at Reynard, who shook his head. “There is no difference outside, if that’s what you’re asking,” the fox said. “The king, Mordred, still rules over Albion, and the giants still come by every hour or so to throw stones in the harbor.”

“I really hate those creatures,” muttered Jack.

“I think the feeling is reciprocated,” said Reynard. “At one point they were offering to tell the king the rest of your companions were dead if they’d just give

you

up.”

Jack swallowed hard and managed a weak smile.

“Don’t worry, Scowler Jack,” Uncas said, patting him on the knee. “We told ’em we’d just as soon do you in ourselves.”

“Thanks, Uncas.”

Chaz exploded. “So what good did we do?” he exclaimed, waving his arms in frustration. “We found his true name! And we convinced the other one t’ Bind him! And it didn’t change anything at all!”

“We’ve only done half the task,” John reminded him. “Our friend Hugo is still trapped somewhere in the sixth century, and that’s what caused England to become Albion. When we confronted Madoc, and Meridian Bound him, it was only the second century. So obviously something still happens four hundred years later that we have to prevent.”

“And how are we supposed to do that?” asked Jack.

“There are three more slides,” Reynard reminded them. “I do not think the Prime Caretaker would have left them as mere redundancies. I think each one may have a purpose in and of itself.”

Fred nodded enthusiastically. “I agree. Each time you’ve gone through a portal, you’ve come back with something you needed to know.”

“That’s true,” Jack agreed. “The trip to Miletus revealed that Mordred and the Cartographer were brothers, and the second, to Alexandria, allowed us to tell Meridian how to Bind his brother.”

“Curious, though,” John pondered. “He already knew the words to do it. I think he just never would have done it if we hadn’t provided the motivation.”

“He needed t’ know,” said Chaz. “He needed t’ know what his brother would one day become. And there was no one else t’ tell him but us.”

“So what now, John?” asked Jack. “I don’t think we can handle another jaunt right away. I’m exhausted.”

Chaz, already dozing, snored in agreement.

John looked to Reynard. “If we take a short nap and regain a bit of vigor, do you think the giants will cause trouble?”

The fox shook his head. “They can disturb and harass, and they may be able to damage your ship in the harbor by throwing stones. But I think it will be safe enough for you to remain, for a short while.”

“Good,” John replied, already stretching out on the floor. “I feel like I haven’t slept in centuries.”

After a few hours, Uncas and Fred regretfully roused the companions. “Sorry t’ wake you, Scowlers,” said Uncas, “but the giants have rallied.”

John groaned and stretched, and Jack rose, looking around the room. His face fell when he saw the burlap bag in the corner, untouched as they had left it.

“Damn and double-damn,” he breathed. “I’d really hoped that I dreamed that part.”

Chaz jumped to his feet. The brief sleep seemed to have recharged him fully. “So what is the plan?”

John was examining the packs that the badgers had prepared for them. There were rations of food, and containers of fresh water, along with two other items: the Serendipity Box and the Little Whatsit.

“The latter is for any emergencies what may arise,” explained Uncas, “an’ the former, for when you’re well an’ truly up t’ your necks in it. Just in case.”

“I already used the Box,” John said.

“I know,” said Uncas, “but they haven’t.”

The badger was right. According to Bert, they could each use it once, and Jack and Chaz hadn’t touched it yet.

Before John could ask anything else, they were interrupted by a tremendous crash from outside. There was a cacophony of howls, and what sounded like pounding surf, and worse, the laughter of giants.

Fred indicated to the others that they should remain in the projection room, and he rushed out the door.

A few seconds later he reappeared, helping Reynard, who was limping and bleeding badly from a gash in his skull that had nearly cost him an ear.

The companions hurried over to the wounded fox. “What’s happened, Reynard?” John asked, concern etched on his face. “Are you all right?”

“I shall live,” Reynard replied, “but you have suffered a loss, I am sorry to say.”

“What loss?” asked Jack.

“Your ship,” Reynard said, still in shock. “The

Red Dragon

. The giants have succeeded in destroying her. She’s gone, shattered, sunk.”

So that was it, John realized. The

Red Dragon

had been their only means of escape from Noble’s Isle. Whatever success they were to have in defeating Mordred would now only be found inside the slides left for them by Jules Verne.

“Uncas,” John instructed, “fire up the Lanterna Magica. We’re running out of time.”

The third slide showed a grassy hilltop, on what seemed to be a summer day. There was a single tall oak tree at the crest of the hill, and underneath, a young man, barely more than a boy, sleeping peacefully.

“Do you know who it is?” Chaz asked the others. “He’s too young to be Meridian or Madoc.”

John shook his head, as did Jack. “Not a clue, I’m afraid,” Jack said, “but I mean to find out.”

The three companions said their good-byes to the badgers, and thanked the injured fox for his attempts to protect their ship. Then, Chaz leading this time, they stepped into the projection.

Unlike the previous slides, which had opened into cities on the sides of walls, this one opened a portal into open air. The three men moved quickly through the gossamer layers and turned around to look at the odd phenomenon.

“Strange, isn’t it?” said Jack. “It’s a bit like the door in the wood, John. There’s no back side to it when you come around the other side.”

“At least this one isn’t going to close on us,” John replied. “We’ll have to remember it’s to the east of the tree when we return.”

There was nothing else in sight, save for miles of rolling hills and clusters of trees. No buildings, no structures of any kind, as far as they could see. Just the tall oak and the sleeping boy.

He was dressed heavily, with a cloak over his tunic and shirt, and his boots were fur. He’d come from some land that was colder than this, wherever they were.

“It’s England, of course,” said Jack. “Can’t you tell by the light?”

“If you say so,” John said, unconvinced. “Shall we wake him up? He’s obviously the reason Verne had us come here.”

The others agreed, and John reached down and shook the boy’s shoulder once, then again. Finally the boy opened his eyes and gave them a half-awake smile. “It’s about time,” he said, sitting up. “I’d begun to think you would never get here.”

His speech was a mix of Gaelic and Old English, but it was not difficult for John and Jack to understand. Chaz couldn’t quite make it out, but he seemed to get the gist of it. The boy had been waiting for them.

“You were expecting us?” John said in surprise, offering the boy a hand up.

The boy rose to his feet and dusted himself off. “I was expecting … someone,” he replied. “I blew the horn almost an hour ago.”

He showed them a curved, golden horn that had Greek letters etched into the sides. “My mother gave it to me,” he explained, “and said to use it only in a time of great peril.”

Jack looked around at the countryside, which seemed empty of life, save for a few mice on the hill and a distant bird, circling in the sky. “Peril?” he asked. “Did we miss it?”

The boy reddened. “I know. I must seem a fool for using it so lightly. But I lost my way, and I’m out of food and have little water, and I didn’t think I could hold out much longer just wandering around.”

“How long have you been traveling?”

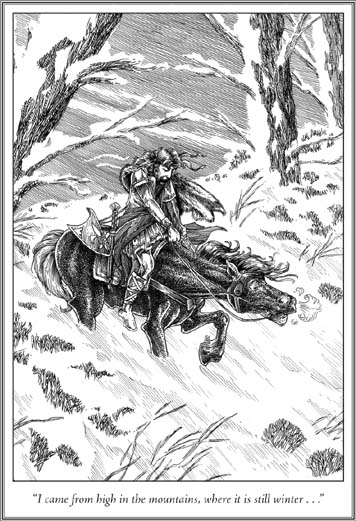

“A month,” the boy answered. “I came from high in the mountains, where it is still winter, riding hard. I had to abandon my horse when I crossed the water, and I’ve been walking for several days now. Then today I decided to use the horn. I’m already late, and if I arrive too weak from hunger and thirst, then I’ll have no chance at all in the tournament.”

“What tournament?” asked Jack. “Where are you going?”

“The tournament at Camelot,” the boy said, “to choose the High King of this world and of the Unknown Region.”

The companions looked at each other in astonishment.

“What’s your name, lad?” asked John.

“I’m called Thorn,” the boy said. “Have you got anything to eat?”

They opened up the packs prepared for them by the badgers and held off asking anything further while Thorn tucked into the food and drink. John stood a few feet away, watching, while Chaz busied himself reading the Little Whatsit to see if there were any language translation aids to be found there.

Jack walked around the other side of the tree, watching Chaz with an odd expression. “Do you get the impression,” he said to John, “that the Chaz we’ve ended up with isn’t the one we started with?”

“I know what you mean,” John replied, looking over his shoulder at the former thief and self-confessed traitor, who had become completely absorbed in reading the badgers’ handbook. “At first I thought it was just that he had a knack for languages. He is a chosen Caretaker, after all. He had the aptitude, even if he’s from a timeline where he never became the educated man we know. But it’s more than just remembering Greek, or being able to translate it, then speak it, after only

days

among the native speakers. He isn’t struggling—he’s

fluent

. He’s … he’s …

changing

, isn’t he? Almost like …”

“Almost like he’s becoming a lot like another scowler we know and respect?” said Jack.

“Something like that.”

“How can that be?” asked Jack. “Isn’t it a different world altogether? He can’t be our Charles.”

“It wasn’t a different world for Bert,” John replied. “He was, in many ways, ‘our’ Bert—at least he claimed to be. Maybe, in some small way, this is still ‘our’ Charles.”

“Hey,” Chaz called out, marking a page in the Little Whatsit. “I think I finally found a place that sounds worse than Albion. According to th’ book, it’s called ‘Cambridge.’”

It was a full minute before John and Jack could stop laughing.

“I don’t get it,” said Chaz.

“Uncas will explain it to you later,” John told him.

“Well,” Jack said, looking at their empty satchels and drained flagon, “so much for our provisions.”

“We haven’t even been here an hour,” John replied, “and we aren’t even sure what we’re supposed to do. Why don’t you just go back into Sanctuary and restock? That way we’ll be prepared for anything and won’t go hungry later.”

“Good idea,” Jack answered, gathering up the bags and heading around the hill. “I’ll be right back.”

“Is Sanctuary where I summoned you from?” asked Thorn. “When I blew Bran Galed’s horn?”

“We weren’t summoned,” John said. “It was just a coincidence that we came when we did.”

“Really?” said Thorn. “What did you come here for?”

Before John could explain, Jack came running up to the tree, a panicked expression on his face.

John took his arm. “What is it? Are the badgers all right?”

“I don’t know!” Jack exclaimed. “I didn’t have the chance to look!”

“Why not?”

“The portal!” Jack said with rising terror in his voice. “It’s gone! We can’t get back!”

The tournament had gone forward in a spectacular fashion, overseen by the Lawgiver. There had been contests of not only physical prowess, but of intellect.

“Merlin nicknamed it ‘Heart, Hand, and Head,’” Hank told Hugo. “Apparently, the contests are based on a series of trials once used in competitions at Alexandria.”

“Like the Gordian knot?” asked Hugo.

“Something like that,” Hank answered.

The contests went on throughout the day, and more than half of the hundred or so who had come to compete were eliminated. There were very few life-threatening injuries, and no deaths whatsoever.