The Intelligent Negotiator (11 page)

Read The Intelligent Negotiator Online

Authors: Charles Craver

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General

If you can induce your opponents to make the first offer, you are also more likely to induce them to make the first concession. Studies indicate that individuals who make the first concession during bargaining encounters do less well than their opponents.

4

These persons tend to be more anxious negotiators who are afraid they will not achieve agreements if they do not move quickly. They thus make more and larger concessions than their more

patient adversaries. But the logistics of discussion favor this as well: After their initial offer and your counteroffer, it is natural for you to look back to them for the first concession; it is their turn to disclose the next position. This approach increases the probability that they will make a greater number of concessions than you make.

When opponents begin with offers that are more generous than you anticipated, you must act quickly to take advantage of the situation. Modify your planned opening offer in your favor to skew the discussions in your direction. You are in the position to take advantage of the fact they think you deserve a better deal than you believe you should get. Don’t hesitate to defer to the superior judgment of opponents who conclude that you are entitled to more than you had hoped to achieve!

I have a friend who represents plaintiffs in medical malpractice cases. He had a client with a claim he thought was worth $75,000. When he began the serious discussions with the insurance company representative, it became clear that his opponent thought the claim was worth more than he did. He immediately raised both his aspiration level and his planned opening demand to take advantage of this unexpected development. He finally settled his “$75,000 case” for $250,000. When he was done, his only concern was whether he could have obtained more. The insurance company representative must have known something that he did not. For example, the representative may have known that the treating physician was drug- or alcohol-impaired when he treated the claimant. My friend had no information of this kind, but he was certainly willing to accept his opponent’s unanticipated generosity.

If you are sitting across the table from an adversarial negotiator, chances are that your counterpart will begin with a wholly unrealistic offer favoring him or herself.

What should you do when this happens? Don’t make the mistake of responding to unreasonable opening offers in a casual manner. That behavior may allow your counterpart to think his or her positions are not outrageous. When negotiators begin with absurd positions, they almost always know that their offers are outlandish, and they expect you to say something negative about their position. If you fail to do so in a forceful way, they begin to think their unrealistic offers are acceptable—and they raise their expectation level. If your counterpart opens this way, politely but forcefully indicate your displeasure with his or her opening position. Tell this person directly that the offer is untenable. This type of negotiator expects you to do so and actually feels comfortable when you do. They are merely information gathering in an extremely aggressive manner.

In some instances, you will be able to persuade counterparts who have made opening offers to “bid against themselves” by making additional offers. Try this by asking: “Is that the best you can do?” or alternatively: “You’ll have to do better than that, because …” If you provide them with a reason to make you another offer (for example, you have received a better offer from a competing party), they may give you a more generous position statement. If you are lucky, a careless counterpart may make several concessions before you even state your own opening position. Another way to generate the same effect is to employ the strategic use of silence. Following opening offers or subsequent concessions, look dejected and remain silent, and you will be amazed how often counterparts fill the voids with additional position changes.

Is there an easy way to induce counterparts to make the first offer? Unfortunately, there is not. In some circumstances, however, we expect one side to go first as a

matter of common practice. For example, people who put their house on the market are expected to provide a listing, or asking price. Retailers are supposed to list or state the price of the commodities they are selling. Employers offering applicants new positions are usually expected to either list in the job announcement, or state in the job offer the salary involved. Other than these types of situations, the marketplace does not suggest who should go first. When the time comes, remember the advantages to be gained when you induce your counterpart to make the first offer.

P

UTTING

Y

OUR

P

RIORITIES IN

P

LACE

The Intelligent Negotiator wishes to maximize the joint return of both parties. To do this, you must know which items are most and least valued by your counterparts. Like your goal priorities (the ones you set in

chapter 2

), your counterparts’ priorities are critical. Listen carefully to discover what they are.

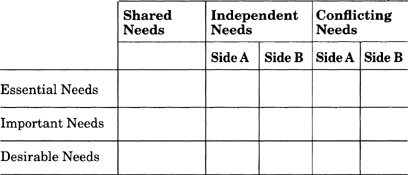

Identify Conflicting Priorities

The various items to be exchanged can be classified as “essential,” “important,” and “desirable.” Which terms do they feel they

must

have, they strongly

wish

to have, and would merely

like

to have? Once you and your counterparts begin to disclose your respective values, you can evaluate the degree to which your own objectives conflict with the goals of the other side. In some instances, both of you may actually desire the identical distribution of the items in question, allowing you to enhance your respective interests simultaneously. Through an appropriate resolution of these

“shared needs,”

you can maximize the joint return.

Table 1

J

OINT

N

EEDS

C

OMPARISON

In their book

Interviewing, Counseling, and Negotiating,

5

Professors Robert Bastrass and Joseph Harbaugh created a table that graphically highlights the different levels of party needs (see

table 1

).

You may discover that one side desires items that are of no particular interest to the other side. The participant who values the items should be given these terms. Why would the other side be so generous? Being accommodating with respect to items the other side values and you do not can increase the likelihood that you will get other terms that you value. By resolving these

independent needs

appropriately, each side enhances the likelihood that it will obtain the terms it prefers.

Proficient negotiators should work to ascertain the areas of

shared

and

independent needs

to ensure the proper distribution of these non-conflicted items. When negotiators attempt to resolve disputes over their

conflicted

needs,

they must try to remember the degree to which they actually want these items. If one side considers a disputed matter “essential” while the other views it as “important” or “desirable,” the term should be given to the side that values it more in exchange for something the other side considers more significant. For example, if a prospective employee considers three weeks of vacation critical but the hiring company does not, while the company is absolutely unwilling to provide employees with company cars, the employee would be better off trading her claim to a company vehicle for an extra week of vacation, enabling both parties to obtain the items they value more.

When negotiating parties encounter direct conflicts involving items that both sides value equally, they must look for appropriate compromises. If there are several issues of this kind, the parties may agree to divide them up. Or one may concede one “essential” term for two or three “important” items. For example, a car dealer may agree to include a better audio system for a higher price. The buyer values the system at the $450 retail price, while the dealer values it at the $300 dealer cost. If one participant tries to claim all the conflicted items, an unproductive impasse is likely to result. It thus behooves both parties to look for ways in which the conflicted issues can be resolved amicably rather than place one side in a position that requires them to do all the yielding. An effort should always be made to generate compromises that provide each side with the sense that it got some of what it really wanted in exchange for concessions on other desired items.

Competitive/adversarial negotiators, particularly those with a win-lose mentality, may be hesitant to accept a cooperative approach. They may think that their aggressive tactics will enable them to claim more “essential” and “important”

items for themselves. While they may occasionally achieve such skewed results from less proficient or naive opponents, they can rarely hope to do so against skilled adversaries. Furthermore, when ongoing relationships are involved, those who regularly claim the lion’s share of items for themselves may find their personal and professional relationships deteriorating. Before they know it, they may find themselves divorced from their spouses or business partners.

Competitive negotiators should appreciate the benefits that can be derived from win-win bargaining techniques. To the extent that you can satisfy opponent interests at minimal or no cost to yourself, you can greatly increase the likelihood of mutually beneficial results. You can also enhance your ability to claim more of the conflicted items for yourself. So long as you are able to obtain what you really value, you should not be disappointed by the fact that your opponent’s interests have also been satisfied. Instead of asking whether you did better than your opponent, ask whether you are pleased with what you got. The fact that your adversary did worse is of little consolation if you also failed to attain beneficial results.

M

ULTIPLE

-I

TEM

N

EGOTIATIONS

Multiple-item negotiations—such as those involving long-term projects, employment contracts, or even divorce proceedings—are complex. Here are a few factors you should keep in mind to be as effective a negotiator as possible. Watch how your counterparts begin this stage of the discussion. Since negotiating over ten or twenty items simultaneously is impossible, multiple-item negotiators break

their discussion into manageable segments of three or four topics per segment. Most negotiators begin the talks with a group of either their most or their least important terms, rarely mixing important and unimportant topics. Anxious negotiators usually begin with their most valued terms, hoping to resolve them quickly. This is a risky approach. Both sides may value many of the same items, and when one party begins with the most hotly disputed topics, participants may reach a quick impasse and conclude that the gulf between them is too great to achieve a mutual accord.

Intelligent Negotiators generally prefer to begin the bargaining process with a discussion of the

less significant

topics for these reasons:

They want to generate quick agreement on these less controversial items. If things progress well, they should be able to reach tentative agreements on many, if not most, of these terms before they get to the more conflicted items.

They want to create a psychological commitment to the bargaining process. By initially focusing on the areas of agreement, rather than the areas of disagreement, these parties are able to agree—tentatively—on many terms, creating a psychological commitment to the bargaining process. As they move toward the more controversial topics, they remember how many terms have already been resolved, and the remaining items no longer seem insurmountable.

Look closely at the groups of items with which your counterparts initiate the serious talks. If they open the discussions with a group of four items, three of which are insignificant to you, but one of which you value, your opponents probably consider all four to be relatively unimportant.

If you can exchange the term you value for one or two of the other items during the preliminary exchange, you will obtain a real gain at minimal cost to yourself.

On the other hand, if opponents begin with four items, three of which you value and one of which you do not, they probably value all four terms. Try to trade the item you do not value for one of the three you consider important. Don’t feel guilty about the fact that you may be obtaining a valuable term for something you do not personally value. When determining the importance of bargaining chips, remember this: The value of items being exchanged is in the eye of the beholder. If I have something you want, you will pay a reasonable price to get it. If you don’t value what I possess, you will give me nothing important for it even if others indicate that they think the item is valuable.