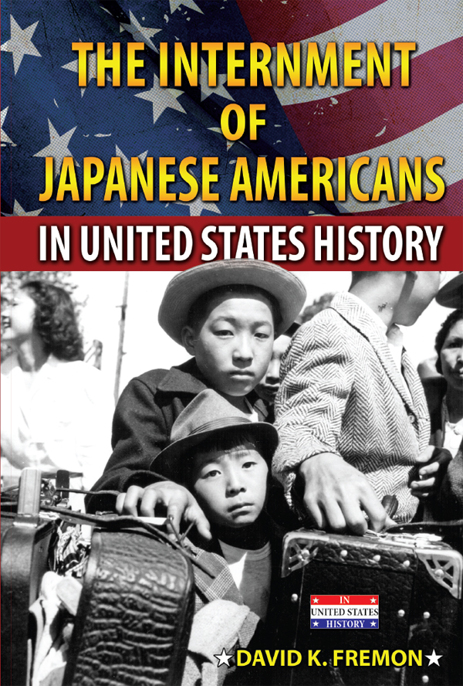

The Internment of Japanese Americans in United States History

Read The Internment of Japanese Americans in United States History Online

Authors: David K. Fremon

Loyalty in Question

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the United States Naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This act forced the United States to enter World War II and declare war on Japan, Italy, and Germany. The mood of the nation turned anti-Japanese. Widespread panic followed the attack and the government ordered thousands of Japanese Americans to be rounded up and moved into government-run internment camps. The loyalty and patriotism of these Americans was questioned, not because they were involved with the bombing, but because of their ancestry. How, in a country which professes so many freedoms, could something like this happen?

In

The Internment of Japanese Americans in United States History

, author David K. Fremon looks at the events behind this ugly episode in American history. Highlighted are the personal accounts of many Japanese Americans who were forced to live through this difficult time.

"…earned a place on our Honor List."

—VOYA

"Fremon is focused and passionate…"

—Booklist

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David K. Fremon has written many magazine and newspaper articles, as well as books on historical topics. Several of his books show past injustices and attempts to correct those injustices.

Chapter 2:

Aliens Ineligible for Citizenship

Chapter 3:

We Looked Like the Enemy

We Must Worry About the Japanese

Chapter 4:

Why Did the Guns Point Inward?

Chapter 5:

They Were Concentration Camps

MAP: Relocation and Assembly Centers

Chapter 6:

What’s This Camp Coming To?

Chapter 8:

Their Job was to Uphold the Constitution

Chapter 9:

A Blot on the History of Our Country

Chapter 10:

We Should Pardon the Government

On the night of December 7, 1941, Shigeo “Shig” Wakamatsu planned to sleep late. The twenty- seven-year-old

Nisei

man (American-born person whose parents were from Japan) kept a busy schedule. While studying at the College of Puget Sound, he worked as a night watchman and receiving clerk at Tacoma’s farmers’ market. He could use the rest.

Instead, he got a jolt. A fellow Nisei stormed into the market and yelled, “‘Hey, Shig, the Japs are bombing Pearl Harbor!’ By the time I turned around, he was gone, he was so excited,” Wakamatsu recalled years later.

1

A startled Wakamatsu dressed hurriedly, then went to a local restaurant. “One of the owners was screaming, ‘By God, when we’re through, we’re gonna kill every Jap!’” Wakamatsu said. “Then he saw me. ‘No, Shiggy, we’re gonna save you,’ he promised.”

2

For Shigeo Wakamatsu and thousands of others in America, the Pearl Harbor bombing altered their lives completely. They were first generation Japanese-born Americans (

Issei

) or second generation American-born Nisei. Although their ancestry was Japanese, they were as American as the Italian-American fisherman, the Irish-American dockworker, or the southern-born farmer. Yet solely because of their ancestry, their patriotism was questioned. For many Americans, the Japanese bombing of the United States Naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii, turned innocent Japanese Americans into monstrous, subhuman “Japs.”

Wakamatsu and other Japanese Americans worked to destroy that image. The following day, they called for a special assembly at their college. Students listened to the radio as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared the Pearl Harbor invasion on December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy.” A friend handed Wakamatsu a piece of paper as they listened. The paper contained the Japanese-American Creed, written only months earlier.

After the president’s speech, Wakamatsu addressed the student body, ending his speech with the creed. The last paragraph of this document read:

Because I believe in America, and I trust she believes in me, and because I have received innumerable benefits from her, I pledge myself to do honor to her at all times and in all places; to support her Constitution; to obey her laws; to respect her flag; to defend her against all enemies, foreign or domestic; to actively assume my duties and obligations cheerfully and without any reservations whatsoever, in the hope that I may become a better American in a greater America.

3

His patriotism should have remained unquestioned. Instead, Shig Wakamatsu and others ended up as domestic prisoners of war. In May 1942—one month before his scheduled college graduation—he was relocated to a detention camp in the Rocky Mountains.

Wakamatsu was not alone. More than one hundred twelve thousand Japanese Americans—seventy thousand of them Nisei—were evacuated from the West Coast in 1942. These children, women, and men were placed in ten relocation centers, mostly in desolate Rocky Mountain sites. Many lost their careers; most lost their property. Although none was ever found guilty or even accused of a war crime, all were treated as if they were traitors.

Even more disgraceful than the government’s action was the reaction of their fellow Americans. During the time of the evacuation, no California politician and few government leaders from anywhere else criticized the West Coast removal.

Earl Warren served as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. As the nation’s chief jurist, he later became known as a defender of individual rights. But as California attorney general in the early 1940s, he spearheaded the drive to oust Japanese Americans from their homes. A regretful Warren was later quoted as saying, “[the evacuation of Japanese Americans was] one of the worst things I ever did.”

4

ALIENS INELIGIBLE FOR CITIZENSHIP

When Commodore Matthew Perry, a United States Navy commander, met with Japan’s emperor, Komei, in 1854, the emperor agreed to end two centuries of isolation and open up trade with the West. Perhaps the four American gunboats with cannon aimed at the royal palace influenced the emperor’s decision.

The new treaty meant little to the average Japanese. For the next thirty years, most of the Japanese visiting the United States were sailors. They stayed in American ports only long enough to unload and load goods.

America already had Asian immigrants at that time. Chinese workers toiled on the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Even while using Chinese workers, white Americans discriminated against them. Racist bullies harassed and even murdered Chinese immigrants.

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed a bill that halted further Chinese immigration. California law forbade the Chinese (as well as African Americans and American Indians) from testifying against whites in court. This, in effect, allowed whites to steal from the Chinese. A “Chinaman’s chance” came to mean no chance at all.

In the 1880s, Japanese workers came to Hawaii to harvest the sugar and pineapple crops. West Coast farms, mines, lumber camps, and railroads also sought Japanese laborers.

Most of the early Japanese immigrants were young men. Like many other immigrants, they planned only to make money and return home, but also like other immigrants, many stayed.

Farmland in the Pacific Coast states of California, Oregon, and Washington was plentiful then. Earlier arrivals claimed the best ground. The Issei took what was left. They worked wonders with this land. Japanese farms yielded crops which were as good as or better than those of white farmers.

The Japanese success startled white settlers. When those workers started owning land and competing with white Americans, many whites started panicking.

Nearly twenty-five thousand Issei and Nisei lived in the United States in 1900, almost all of them on the Pacific Coast. Another hundred thousand would arrive in the next eight years. Westerners noted the increased Japanese numbers.

The San Francisco Chronicle

decried the “complete orientalization of the Pacific Coast.”

1

In 1905, anti-Japanese campaigns stepped up after Japan triumphed over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. Membership in an anti-immigrant group, the Native Sons of the Golden West, increased. The young Earl Warren was one of those new members. The Oriental Exclusion League sought removal of all Asian immigrants. When Japanese immigrants opened successful laundry businesses, whites started the Anti Jap Laundry League.

The San Francisco Chronicle

led a barrage of racist attacks against the Japanese. Headlines warned of “THE YELLOW PERIL.”

2

Soon, the city followed the newspaper. In 1906, San Francisco removed its Japanese students from white schools and ordered them to attend segregated schools in Chinatown.

The Japanese government protested these measures. President Theodore Roosevelt made a so-called gentleman’s agreement with the Japanese government. It stated that the United States would not pass anti-Japanese laws. Japan, in turn, would stop issuing passports allowing Japanese citizens to enter the United States, except for “former residents, parents, wives, or children of residents.”

3

When the Issei became successful, they sent for their families. If they were single, they started families. Many states outlawed marriages between people of Japanese descent and white Americans, but

baishaku-nin

(go-betweens) arranged marriages between Japanese-American men in the United States and eligible women still in Japan. Often, the would-be groom knew nothing more about his bride than the picture she sent. These women became known as “picture brides.”

Facing Discrimination