The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (11 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

A cornerstone of Nuremberg's rise to greatness was its engagement in the financing of industrial ventures in the mines of Saxony. Nuremberg was Germany's gateway to the east, and the major firms had branch offices in Vienna, Prague and Krakow. The fact that its governing council was drawn from the wealthiest merchants ensured that the interests of business would always be well represented. A mirror of Nuremberg's economic power can be seen in the city's success in insisting that its merchants were exempted from tolls in many other German towns. Nuremberg's economic power was respected but also feared: the city fathers were fully aware that the interests of their city had to be defended against predators. That demanded, above all things, a steady flow of accurate information.

Nuremberg's status as an information hub derived partly from its geographic situation, at the confluence of twelve major roads. Martin Luther described the city as ‘the eyes and ears of Germany’, and it would play a critical role in spreading news of his quarrels with the papacy.

47

The role of the international merchant community as a source of information was widely recognised. In 1476 the minutes of the Town Council record a decision ‘to seek advice from

the merchants’ and this would not have been unusual.

48

The steady Turkish advance through the Balkans in the fifteenth century threatened many areas where Nuremberg merchants had invested capital. When war seemed likely, the city merchants would entrust one of their number who had interests in the area with finding out what was afoot. Critical information was frequently shared with other German cities. In 1456 news of the war with the Turks was despatched onward to Nördlingen and Rothenburg. In 1474 when the merchants contacted a friendly source in Cologne for information, they in return forwarded news from Bohemia, Hungary and Poland.

49

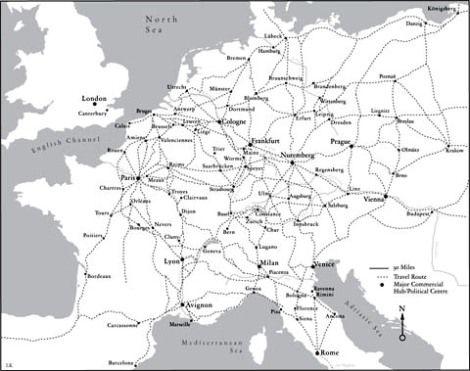

Map 2 Major European trade routes, c. 1500.

To service this far-flung information system the German towns and cities maintained a sophisticated courier network. A regular courier service was in operation between Augsburg and Nuremberg by 1350, and the first surviving city accounts for Nuremberg, which date from 1377, show that the city was already making use of paid messengers.

50

By the fifteenth century Nuremberg had a number of couriers on the city payroll. Notwithstanding the expense, the city made frequent use of their services: in the ten years between 1431 and 1440 Nuremberg sent out 438 messengers.

51

This period of intense activity

coincided with the latter stages of the Hussite wars, and in such turbulent times it was vital that the merchant community be aware of the latest developments in case their goods were impounded – either where they were traded or in transit. The city fathers regarded the outlay on messengers as money well spent.

With these city courier services the south German cities had established a system that fell halfway between the traditional ad hoc system of merchant correspondence and the diplomatic networks beginning to be developed by Europe's leading princes. They were able to take advantage of the same synergy of interest we have observed in that other great merchant republic, Venice.

In the sixteenth century the network of German city courier services would be linked up to provide a regular weekly service as an adjunct and later rival to the imperial post. Because the imperial post followed the major trade routes between the Netherlands and Italy, the north/south trade axis through the Empire was not well served, and this is where the city post came into its own. But this was for the future. At the close of the Middle Ages the merchant posts had established an intense and permanent node of communication between Venice and southern Germany, linking two of Europe's most sophisticated merchant economies. In turn this established a second vital stream of information to mirror the route through the western Alps linking Italy with Paris and Bruges. Venice and Nuremberg, the two great trading centres of the age, had established an undoubted primacy as information hubs south and north of the Alps. It was no accident that these cities would also be pioneers in the new information age that dawned following the invention of printing.

CHAPTER 3

The First News Prints

I

N

the new commercial world of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Europe, wealth brought many privileges. Men of power had long enjoyed the luxury of space: land on which to hunt; large and eye-catching villas on the main streets of Europe's richest cities. Now, thanks to international commerce, they were able to fill these houses with beautiful things. Their homes became the visible symbols of their wealth. They built gardens, wore fine clothes, and filled their rooms with exquisite objects: tapestries, sculpture, pictures and curiosities, the horn of a unicorn or precious stones. They also began to collect books. For the development of European intellectual culture the new vogue for books was highly significant. Until this point books were essentially a utilitarian tool of the professional writing classes. Books were accumulated only where they were used: in religious houses, by teachers in the new universities. Students might own one or two texts, often laboriously copied from dictation or from a rented master copy. It was only in the late fourteenth century that the building of a library became an important part of elite culture.

Books and learning played a critical role in the new culture of the Renaissance. Scholars placed the rediscovery of lost classical texts at the heart of an exciting new world of intellectual exploration and literary fashion.

1

Europe's major commercial hubs, in Italy, Germany and the Low Countries, became the centres of a new trade in the manufacture and decoration of books.

As long as each book had to be hand-copied from another manuscript, the pace of growth was limited by the availability of trained scribes. Inventive spirits in different parts of Europe began experimenting with ways to speed the process by mechanisation. The honour of having first mastered the craft of printing would go to a German, Johannes Gutenberg, the manufacturer of pilgrims’ mirrors of a decade before.

2

In 1454 Gutenberg was able to exhibit at the Frankfurt Fair trial pages of his masterpiece, a Bible, that he would go on to

produce in 180 identical copies. Europe's book-owning classes were not slow to understand the importance of what Gutenberg had achieved. Attempts to protect the secret of the new technology were unavailing. Soon craftsmen were introducing the new technique of book manufacture to all corners of Europe.

3

The technological brilliance of print was indeed impressive, but the first generation of printers was remarkably conservative in the choice of books they brought to the market. The first printed books mirrored very closely the taste of established customers for manuscript books. Gutenberg's Bible was followed by psalters and liturgical texts. Italy's first printers published multiple editions of works by classical authors, the cornerstone of the humanist intellectual agenda. Standard legal texts of civil and canon law, medieval medical and scientific manuals, also became staples of the new market. These were on the whole big and expensive books. It took some time for printers to understand how this new invention might be used to exploit the market for news.

For this reason the news events of the late fifteenth century did not, on the whole, leave a substantial impact on the new medium of print. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 came just before Gutenberg had successfully unveiled his new invention. For the next thirty years printers would be largely focused on mastering the new disciplines of a marketplace suddenly awash with unprecedented numbers of books, not all of which found customers. News of the conflicts in France, England and the Low Countries, and the darkening clouds gathering over the eastern Mediterranean, was spread by largely traditional means: in correspondence, and by travellers. The fall of Negroponte in 1470 and the siege of Rhodes in 1480 were the first contemporary political events to find a significant echo in print: the threat of Turkish encroachment, here as later, stimulated a pan-European response. Printed copies of the Pope's appeal for coordinated action for the defence of Rhodes were widely circulated.

4

But these were ripples on the pond.

For as long as the new industry remained geared to the production of large books for traditional customers, the reporting of contemporary events would remain a subsidiary concern. The expansion of print into new markets proceeded by tentative steps. First, printers would learn the value of varying their output by publishing small items for volume sales (cheap print). Then they would make experimental use of print to share news of the discoveries of faraway continents in the age of exploration. But it was only in the early sixteenth century, a full seventy years after Gutenberg published his Bible, that the world experienced its first major media event, the German Reformation.

The Reformation catalysed a movement of powerful change that destroyed forever the unity of Western Christendom. It also alerted Europe's nascent

printing industry to the potential of a whole new mass market for printed news of contemporary events. The news market would be changed for ever.

The Commerce of Devotion

In 1472 the first printers in Rome, Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, appealed to the Pope for help. Their publishing house stood on the brink of failure. Their printing shop, according to their piteous petition, was ‘full of printed sheets, empty of necessities’.

5

They had to this point manufactured an impressive 20,000 copies of their printed texts: but they could not sell them. Theirs was not an unusual experience for the first generation of publishing pioneers. The first printers were guided in their choice of texts by their most enthusiastic customers. The universities wanted texts; scholars wanted the classical works admired by humanists. The result was that many of the first printers produced editions of the same books. It turned out they had given too little thought to how they would dispose of the copies. The market in manuscripts was close and intimate: the scribe usually knew the customer for whom he copied a text. Now printers faced the problem of disposing of hundreds of copies of identical texts to unknown buyers scattered around Europe. The failure to resolve these unanticipated problems of distribution and liquidity caused severe financial dislocation. As a result a large proportion of the first printers went bankrupt.

For the shrewdest among them, salvation lay in close cooperation with reliable institutional customers: the Church or State. In the last decades of the fifteenth century the rulers of a number of Europe's states began to experiment with the mechanisation of some of the routine procedures of government. The use of printing to publicise the decisions of officialdom would in due course become one of the most important aspects of the new information culture.

6

But for the first generation of printers the Church would be the new industry's most significant customer. Alongside the numerous prayer books, psalters and sermon collections, church institutions also began to contract printers to mechanise the production of certificates of indulgence.

One of the ironies of Luther's later criticism of indulgences was that they were not only hugely popular, but an early mainstay of the printing industry.

7

After several centuries of evolution the theology of indulgences reached its mature form in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

8

In return for the performance of pious acts – participation in a pilgrimage, contribution to a Crusade or church building – the repentant Christian was offered the assurance of remission of sin. The practice was closely associated with the doctrine of purgatory, to the extent that the length of the remission, often forty days,

was precisely quantified. The contribution was acknowledged with a receipt or certificate: initially on parchment or paper, and handwritten.