The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (56 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Despite this mis-step, it is obvious that the late seventeenth-century proliferation of newspapers in England would have been unthinkable without the healthy advertising revenue generated. In the early eighteenth century the new journals also relied heavily on advertisements. By the end of its run

The Tatler

carried as many as eighteen in each issue, and in

The Spectator

they took up half the total space.

45

They also generated the entirety of the profits. These more upmarket periodicals advertised a more exotic variety of goods reflecting the commercial vitality of London: wigs, slaves, birdcages, shoe polish, cosmetics and medicines.

Advertisements played an even more crucial role in the development of a provincial press. With far more limited pools of potential customers who were prepared to pay two pence for a weekly news-sheet, it was hard to envisage turning a profit from the cover price alone. Allowance had to be made for the profit to the seller and the cost of cartage to bring copies to a dispersed circle of readers. The grim economics were set out with brutal economy by Thomas Avis, editor of

The Birmingham Gazette

. Because of local competition, Avis

was attempting to sell his paper for three halfpence. This was an uphill struggle:

That a great deal of money may be sunk in a very little time by a publication of this nature, cannot seem strange to anyone who considers, that out of every paper one half-penny goes to the Stamp-Office, and another to the person who sells it; that the paper it is printed on costs a farthing; and that consequently no more than a farthing remains to defray the charges of composing, printing, London newspapers, and meeting as far as Daventry the post; which last article is very expensive; not to mention the expense of our London correspondent.

46

With these considerable expenses to meet from a residual farthing a copy, this paper would have run at a loss had it not been for advertising income. Here we might consider the sounder economics of the

Western Flying Post

, which by the mid-eighteenth century might cram up to forty advertisements into its four pages. At a profit of one shilling and sixpence each (after tax) the income, £3 4s 6d, would exceed the profits from sales of over 1,500 copies (an unlikely print run for a paper serving rural Somerset and Dorset).

47

If the paper was only clearing the farthing claimed by Avis, then this advertising revenue returned more than selling 3,000 copies. Advertising was a lifeline.

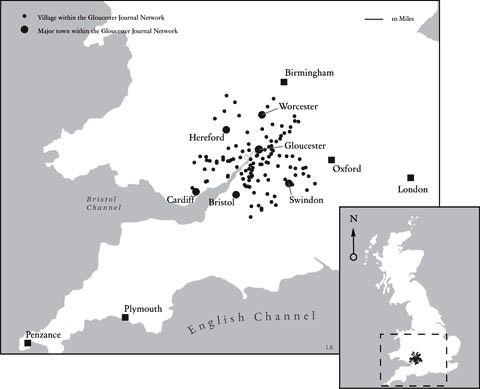

To secure this revenue stream proprietors had to convince their readers that their advertisements would reach a wide circle of potential readers. County papers expended considerable effort to create markets in towns and villages round about. Most papers maintained a standing arrangement with networks of booksellers or grocers where papers could be purchased and advertisements delivered for placement in the next paper; these addresses were usually listed on the final page. One of the most ambitious of these networks was that set out in

The Gloucester Journal

of 1725, which described thirteen divisions or circuits that carried the paper into twelve English and Welsh counties spread over an area of 11,000 square miles.

48

The Gloucester Journal

could be read in Glamorgan, in Ludlow in Shropshire, and as far away as Berkshire. In these farthest reaches

The Gloucester Journal

would be rubbing up against papers printed in other cities (most obviously Bristol and Birmingham) and the competition for advertising revenue was undoubtedly intense. Nowhere was this more the case than in London, with its numerous papers and journals. By the mid-eighteenth century the market for advertisements was itself beginning to segment, with different papers specialising in particular sub-markets: medical elixirs, theatre announcements, and so on.

49

All sought to impress potential advertisers with their wide circulation, and, increasingly, the quality of their readership.

Map 3 The circulation network of the

Gloucester Journal

, 1725

It is in this context that one needs to see Addison and Steele's celebrated and much cited boast that each copy of

The Spectator

would be seen by twenty readers.

50

The claim actually originates rather earlier, in

The City Mercury

in 1694, one of the London advertising papers.

51

It is a multiplier frequently cited by scholars of the newspaper industry when calculating the impact and reach of eighteenth-century papers, but this is not what Addison intended. An, optimistic assessment, it was based on no systematic data, and was little more than a well-judged pitch for advertising business in a crowded market.

52

As a generalisation on which to build calculations of readership it has little value.

Nevertheless such claims do point up the energy with which publishers pursued advertising, which played a crucial role in the development of the news industry not just in the most obvious sense of making marginal operations viable. We may identify, in addition, three consequences of long-term significance. Firstly, the inclusion of advertisements was an important way in which printed newspapers differentiated themselves from manuscript news-books.

53

Until this time the two traditions had been utterly intermingled, mutually furnishing intelligence and copy, and serving overlapping readerships. But manuscript news services never included advertisements; and although they continued into the eighteenth century (robustly in places like France where newspaper publication remained more restricted),

54

the two traditions now began to diverge more dramatically. In the eighteenth century, newspapers served far broader and more numerous clienteles, and finally developed as a self-consciously independent genre. The importance of advertising to this process is signalled by the developing practice of reserving the whole front page of a newspaper for advertising, rather than placing advertisements at the end. This had become the habitual practice of the London papers by the end of the eighteenth century (and in some cases would only be abandoned in relatively recent times).

55

Secondly, by providing a robust income stream, advertisements brought closer the day when newspapers could hope to be self-financing, and furnish their editors with a decent income: perhaps ultimately the funds to employ additional staff. To this point, the publishing of newspapers had been almost always the enterprise of a single man, and this left little enough time or space for editorial creativity. In principle the rising financial returns from advertising revenue might over time encourage a tradition of genuine editorial independence. In the short term governments were too wary of the press to allow this to happen. It is surely relevant in this connection that the Stamp Act of 1712 imposed, in addition to the obligation of stamped paper, a swingeing fee for each advertisement. The precipitate fall in advertising revenue that inevitably followed was probably a greater cause of newspapers failing than the stamp itself.

56

Finally, advertisements played an important role in humanising the press. The first papers were, as we have seen, rather clinical and distant. They offered a sequence of reports of overwhelmingly foreign news. The reader might be flattered to be incorporated into these previously closed circles of knowledge, but it was hard going. Advertisements brought the everyday lives of the local public directly into the reading experience of their fellow customers. They could marvel at the rich furnishings and clothing that citizens had somehow mislaid; empathise with the experience of unreliable servants; enjoy the wicked, guilty pleasure at the humiliated and exasperated husband forced to make a public declaration that he would no longer be responsible for his wife's debts.

57

Readers could revel in these vignettes of chaotic and disturbed lives; they could feel the pain of those who had lost all their worldly goods by fire; they could wrestle with the conflicting emotions of incredulity and hope raised by

advertisements for patent medicines. They could marvel at the villainy of fugitive criminals, whose crimes and physical characteristics were often described at some length, and they could share with anxious neighbours their fears that such villains could be lurking in the vicinity. It has been suggested that these crime reports, placed by the local authorities as advertisements, made a significant contribution to law enforcement at a time when policing was rudimentary and citizens were necessarily required to contribute to upholding public order.

58

Certainly, in an age before the editorial, and where a large portion of the news continued in the hallowed tradition of the foreign despatches, these advertisements allowed papers to offer some echo of the vivacity and merriment purveyed by pamphlets and broadsheets. It is no accident that in the early eighteenth century, when the metropolitan news market was first embracing the culture of advertising, the circulation of

The London

Gazette

, necessarily committed to a more conservative style of dry official announcements, fell precipitously.

59

These scenes of everyday life and titillating visits to the darker reaches of society brought energy, variety and a hint of danger to the news. From this point on advertisements were a staple of the industry.

CHAPTER 15

From Our Own Correspondent

T

HERE

can be no doubt that by the eighteenth century the reading public's appetite for news had generated a considerable industry. In Germany, the Low Countries and particularly England newspapers had captured the public imagination. In London a multiplicity of competing papers fuelled the poisonous politics of the age, and posed those in power unfamiliar problems of news management. But who exactly lay behind this vast increase in the weekly and sometimes daily output of news? Who provided the necessary continuous stream of copy?

It will not have escaped the attention of readers that so far we have met remarkably few of those involved in the actual writing of news. Most of the news men who have featured in these pages have been either the proprietors of manuscript news services, or authors who made their name through the publication of what were essentially advocacy pamphlets in serial form – men like Marchamont Nedham or Daniel Defoe. Most of the great journalists of the eighteenth century were either pamphleteers (Defoe and Swift) or wits (Addison and Steele). So although this was the age when the word ‘journalist’ was first coined, it did not yet describe an independent craft.

The word ‘journalist’ first made its way into the English language at the end of the seventeenth century: the first reported usage is 1693.

1

But like the use of the German

Zeitung

two hundred years before, it did not yet have its modern meaning. A journalist was one who made his living from writing, but not necessarily for the newspapers. The implication was generally disparaging. When the essayist John Toland described the now scarcely known Lesley as a ‘journalist’ in 1710, he was referring scornfully to an emerging class of hired hack who wrote to order, sometimes copy for the newspapers, more often in partisan pamphlets. ‘They [the Tories] have one Lesley as their journalist in London, who for seven or eight years past did, three times a week, publish

rebellion.’ The term was opprobrious and unstable. When Addison in

The Spectator

of 1712 referred to a female correspondent as a journalist, he meant someone who kept a journal or diary ‘filled with a fashionable kind of gaiety and laziness’. The coinage remained occasional. Jonathan Swift tried another variation, ‘journalier’, for newspaper writer, but this did not really catch on. At best the term, derived from the French

journal

('newspaper'), and ultimately

jour

('day'), represented a new emphasis on timeliness in the reporting of current affairs; a circumstance that in the politically charged atmosphere of turn-of-the-century London brought a promise of abundant opportunity for the aspiring writer not overburdened with scruples.