The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (54 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Lists of currency exchange rates were published in much the same way, on a weekly basis under official supervision. Here the published form consisted of a list of European cities, alongside which the prevailing rates of exchange could be added. In Venice the currencies and their rates were both printed on the sheet, though this was rather the exception.

10

Elsewhere the rates were added by hand. As with commodity prices, each city published a single official

list, consigning the task to a trusted official or, in the case of Venice, a publishing firm. In the second half of the seventeenth century the principle of this official monopoly was increasingly under strain. Twice, in 1670 and 1683, the Amsterdam authorities had to intervene to defend the privileges of the appointed exchange brokers from interlopers. The crucial change seems to have come with the introduction of a third major piece of financial data: share prices. In the second half of the seventeenth century the previously rather small number of joint stock companies expanded rapidly. Trading in their stock encouraged the development of specialist financial publications, which listed shares alongside commodity prices, exchange rates and shipping news. Nowhere was this development more pronounced than in the emerging powerhouse of northern commerce, London.

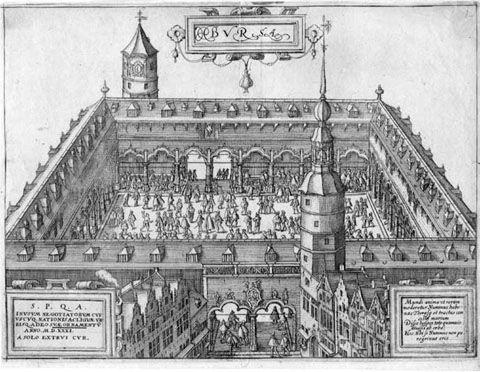

14.2 The Antwerp Bourse. Such places were hotbeds of rumour and disinformation, as well as commercial hubs.

Bubble

In the publication of business data England chose a separate path, almost from the beginning. Uniquely, in England the publishing of commodity data does

not seem to have been an official monopoly. Merchants and traders could instead avail themselves of a wide range of publications. The

Prices of Merchandise in London

, published from 1667 and the successor to the earliest London price lists, was joined from 1680 by Whiston's

Weekly Remembrancer

and from 1694 by Proctor's

Price Courant

.

11

A few years later John Castaing began publication of his

Course of the Exchange

. London had never had its own listing of exchange rates, and this provided Castaing's opportunity. But he improved on it by adding a list of share prices. Castaing, a member of the Protestant Huguenot community settled in London since their expulsion from France by Louis XIV, was an active stock-jobber, and saw here the chance to combine this business with financial journalism. In March 1697 he placed an advertisement for his paper: ‘J. Castaing at Jonathan's Coffee House delivers the Course of Exchange, the price of Blank-Notes, Bank Stock, East India Stock and other things every Post-Day, for 10s per annum.’

12

This advertisement appeared in Houghton's

A collection for the improvement of husbandry and trade

, another innovative financial publication. In contrast to the price lists, Houghton's

Collection

included in each weekly issue an article on a topic of economic or financial interest. This was followed by a select commodity price list and a list of shares. The number of shares quoted was at first large, with as many as 64 listed in mid-1694. This could not be sustained; the list of companies shrank quite rapidly, and in 1703 Houghton's paper ceased publication.

13

Houghton's collection had also included details of the arrivals and departures of ships, trading information that also generated its own specialist publication with the foundation in 1694 of Edward Lloyd's

Ships arrived at and departing from the several ports of England and foreign ports

. This, renamed

Lloyd's list

, continues to this day.

These technical specialist papers remained, however, rather separate from the general press. Although England experienced a rapid proliferation in the number of newspapers after the lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695, these papers offered only very limited comment on the economic life of the capital. The

Gazette

followed the progress of the subscription to the Bank of England in 1694, but once this was accomplished Bank matters were not often alluded to. In 1699

The Post Boy

mentioned a meeting to discuss a union of the East India and English Companies; but there was no comment on the likely effect of such a union, or, in subsequent issues, on the outcome.

14

From 1697

The Post Boy

included a brief passage with the major share prices, but business news intruded most obviously through the placing of paid advertisements. Companies took space to advertise meetings of their General Court. The launch of companies, and particularly projects, took up many inches of news print. This was a great era of projecting. Schemes of land reclamation, patent

diving bells, new inventions and trading schemes made their optimistic pleas for investors’ money. Between 1695 and 1699 lottery schemes often occupied nearly all the available advertising space.

15

This proliferation of lotteries, such as the Million Adventure, the Unparalleled Adventure and the Honorable Undertaking, was a sign of the emergence of a new class of potential investors with little experience in the marketplace and searching for alternative opportunities for investment. It was a potentially combustible mix.

In the two decades after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 the London economy embarked on a period of sustained growth. The more settled political climate allowed for a degree of fundamental institutional innovation: the foundation of the Bank of England, the consolidation of the national debt, the re-coinage of 1696.

16

All of these remarkable developments, and the extra-ordinary boom in venturing and new companies, inspired a sustained effort to understand the changes under way. Most of these disquisitions on trade appeared in traditional pamphlet form, though the periodical press also did what it could to help readers understand the new markets. Between June and July 1694 John Houghton wrote a series of seven articles in his

A

collection for the improvement of husbandry

, attempting to explain the new financial markets to his subscribers. His articles gave a brief history of joint stock companies and explained how trades were made, including such relatively sophisticated instruments as options and time bargains.

17

Defoe's

Review

also discoursed frequently on economic matters, and Defoe was more inclined than most to muse on the general state of the economy. Defoe of course had personal experience of the hazards of projecting, having been a bankrupt in an unsuccessful business career. He never entirely kicked the habit; although the

Review

was drawn off into political topics, his last valedictory issue would comment rather wistfully that ‘writing upon trade was the whore I really doted upon’.

18

The choice of language is significant; the tone of contemporary pamphlet comment was deeply suspicious of projecting, reflecting the perceived moral ambiguity of making money through financial dealings. The questions posed in the correspondence columns of the

Athenian Mercury

focused on the moral hazard of lotteries. Could, asked one correspondent in 1694, a godly man in good conscience partake in a lottery when the lots were disposed by Divine Providence?

19

Despite the considerable amount of ink spilled on economic discussions, and the amount of financial data being published in the business press, it remains very questionable whether this was sufficient, or offered the right sort of information, to be of much use to those entering the markets; particularly at times of rapid price movements. London was a very unusual financial market. To a quite unique extent the capital city concentrated the political

power and financial muscle of the whole nation. It was also of course a port with constant connections to all major European markets. Yet within this sprawling metropolis the financial trading district was concentrated into a very small space. The principal centres of financial power, the Royal Exchange, the East India Company and Exchange Alley (whence stock-jobbers had removed from the Exchange in 1698) were all within a few hundred paces of each other. Visitors venturing into this bear-pit in trading hours found it a cacophony of noise, where those experienced in affairs exchanged information and made trades, all at a speed and in a jargon that outsiders found utterly bewildering. Defoe, whose

Essay on Projects

and

The Villainy of Stock-Jobbers detected

reflect the general scepticism of the age, used his

Review

for a wonderfully inventive denunciation of the lack of scruples in the financial market. The following imagined dialogue caught the irrationality of trading in a market where rumour and the herd mentality could easily trump rational analysis:

One cries, is there a Post? Answer, no; but they have it in Exchange Alley

Has the Government any Express? No, but it is in everybody's mouth in Exchange Alley.

Is there any account of it at the Secretary's Offices? No, but ‘tis all the news in Exchange Alley.

Why, but how does it come? Nay, nobody knows; but ‘tis very hot in Exchange Alley.

20

Those that flourished in this world did so because they had developed their own networks of information and intelligence.

21

It took experience to filter from the cacophony of rumour, reports and advice the news that would move markets, particularly as it was widely believed that some would deliberately circulate false reports to make a profit. Those at the very pinnacle of this edifice of power and money could also be very secretive with commercially sensitive information, the directors of the East India Company and the Bank notoriously so.

The result was that when the markets moved rapidly, as was the case with the notorious South Sea adventure, the printed word offered no real help. The weekly price lists were too infrequent to keep up with the market, and the web of speculation and rumour made little impact on the non-financial papers. This mattered less than one might think, for most citizens were simply the astonished audience for this first great bull market. Rather like tulipmania, the vast majority of dealings occurred within the closed circles of the privileged. The South Sea Bubble was that most satisfying thing: a fraud perpetrated by the elite on itself.

Defoe's

Review

had ceased publication before the South Sea calamity, but it is not likely that he would have spoken out against it. Few voices were raised in criticism as the financial miracle of 1720 unfolded. The South Sea venture was never in any real respect a trading company.

22

To establish a trade with South America depended on an unlikely conjuncture of political circumstances opening a previously closed market, and this prospect had in any case disappeared by 1718. Where it did find success was in creating a counter-weight to the Whig-dominated East India Company and Bank of England, and by sucking in surplus liquidity it had soon raised a huge capital. With no trade in view the directors now made an audacious attack on the Bank by proposing to take on the whole national debt. In a period of frantic negotiation a counter-bid from the Bank was seen off, and the South Sea Company emerged victorious. Such a huge liability, however, required a greatly increased share capital, and a rising share price would also greatly increase the prospects of meeting the Company's obligations. By judicious management of the market this was for a time achieved. Between January and April 1720 the price of South Sea stock had risen from 130 to 300; in the next two months stock appreciated a further 300 per cent. The South Sea stock was not an isolated beneficiary of this frantic activity. Bank and East India stock also rose sharply, and during the year to August a further 190 projects were floated, most as joint stock companies. All were seeking to catch the same hopeful tide that created money from nothing.

At the height of the Bubble newspapers had remarkably little to say about the astonishing events unfolding at the heart of the financial district.

The Daily Courant

, a single-page daily news sheet established in 1702, was the only organ in a position to chart the day on day rises, which seemed so miraculously to be enriching those blessed with stock. On 31 May, South Sea stock moved from 590 to 610; on 1 June from 610 to 760; on 2 June it touched a high of 870 before falling back to 770. Then on 24 June, after South Sea stock had traded at 750 the day before

, The Daily Courant

offered this momentous, but curiously dispassionate announcement: ‘yesterday South Sea stock was 1000’.

23

In such extraordinary times, the weekly or tri-weekly news-sheets despatched to out-of-town subscribers by post could scarcely keep up. Those in the provinces, who would not normally have been subscribers to the

Courant

, generally heard of developments through correspondence with London friends. The papers also gave notice of meetings of the court, and publicised its determinations, as during the summer the Company took steps to enhance its capital further. These heady days, before Parliament intervened to curb projecting, brought a cascade of other calls for capital.

24

The London newspapers were happy to find room for the numerous advertisements placed

by these hopeful entrepreneurs. There were also an increasing number of advertisements placed by those seeking to cash in their shares and invest the profits in property or the accoutrements of wealth. At this point there was little adverse comment; this was reserved for the inevitable search for scapegoats when the Company's share price first faltered and then tumbled precipitously: ‘All is floating, all falling, the directors are cursed, the top adventurers broke.’

25