The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (44 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

French ministers did their best to turn the tide. But it would have escaped no one's notice that the victories for which the king would order a

Te Deum

were often no more than minor skirmishes, whereas the defeats passed over in silence were utterly calamitous. Louis's enemies scented blood. When peace talks were opened in 1709 (ignored by the Paris

Gazette

) the allies would only bring hostilities to a close if Louis joined them in armed action to depose his grandson, Philip, from the throne of Spain. Louis would be forced to choose between his dynastic honour and peace for his shattered country. In these desperate times the king's ministers reluctantly conceded that the insistent attacks from abroad required an answer. When French armies had commanded the field, foreign minister Simon Arnauld de Pomponne could dismiss ‘the million screaming tracts’ that had roused France's enemies abroad as of no account.

18

Now it fell to Torcy, nephew of the illustrious Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to answer them. Torcy had cut his teeth with a series of pamphlets published secretly in Paris under the collective title

Lettres d'un Suisse à un François

. Purportedly the work of a politically engaged but neutral Swiss, these essays were in fact the work of Torcy's client Jean de La Chapelle. Their purpose was to drive a wedge into the allied alliance by warning the German states of the dangers of placing themselves in the protective embrace of the Habsburg Empire.

The

Lettres d'un Suisse

were a considerable literary success, but by 1709 even Torcy was forced to concede that their continuation now served no useful purpose. For, as he admitted to a correspondent in Italy, ‘I would very

much like to be able to soothe [your pains] with some good news, but unfortunately the greater part of what our enemies are circulating is true.’

19

Now the French Crown faced the difficult task of explaining why the hopes of peace (of which many must have been aware from the imported Dutch papers) would be dashed: the war must go on to rescue the king's honour and uphold his obligations to Philip of Spain. In these desperate times Louis spoke to his people directly, in a circular letter ostensibly addressed to the governors of the provinces. Printed in numerous editions, this frank and moving exposition achieved a massive circulation. It marked a sea change in the propaganda priorities of the king. For as Joachim Legrand, a gifted pamphlet writer of these later years, put it to Torcy:

It is not enough that the actions of kings be always accompanied by justice and reason. Their subjects must also be convinced of it, particularly when wars are undertaken which, although just and necessary, nearly always bring so much misery in their wake.

20

The king's address helped rally the French nation for a last desperate effort; certainly the allies were taken aback by the recovery of French morale, and realised that they had overplayed their hand. The first signs of a weakening of English resolution led to a new onslaught of Torcy's propaganda effort, ably seconded by Legrand. In the end it was probably Philip of Spain's victory over his Habsburg challenger that proved most decisive in ending the war, but the emissaries did not operate in a vacuum. The groundwork for the peace treaty signed at Utrecht in 1713 had been carefully laid by a torrent of pamphlets, in large measure orchestrated by the contending parties, but never wholly under their control.

Restorations

In England following the Restoration of 1660, Louis XIV had one fervent, if for the time being secret admirer: the king, Charles II. Skilfully riding a tide of popular sentiment exhausted by the austerities and hypocrisies of the Republic, Charles displayed a charm and public optimism that caught the mood of the moment. Beneath this appealing persona, however, Charles was deeply scarred by the long years of deprivation and humiliations abroad. If he conquered, to an extent, the natural instinct for revenge, he still aspired to rule, and to prevail, against the whirlwind of conflicting expectations aroused by his return. For this, he required a complaisant press. This opened the way for a fascinating conflict between a devious and stubborn monarch and a publishing

community anticipating a return to the vigorous exchange of opinions that had preceded the sour austerities of Cromwell's personal rule.

21

The newspapers inherited from the Commonwealth were soon put into reliable hands. Marchamont Nedham was too associated with Cromwell to hope for further employment, and prudently departed for Holland. But Henry Muddiman, a schoolmaster turned journalist who had attached himself to the architect of the Restoration, General George Monck, successfully contrived a change of allegiance alongside his patron. His

Parliamentary Intelligencer

was continued, though tactfully renamed

The Kingdom's Intelligencer

.

22

Despite these promising beginnings it did not take long for Charles's view of the press to be made manifest. In June 1662 Parliament passed the Licensing Act, requiring all printed books to receive prior authorisation. The upholding of these regulations was placed in the hands of Sir Roger L'Estrange, appointed to the new post of Surveyor of the Press.

23

L'Estrange was a rather unusual newspaper man in that he believed that in a well-ordered world newspapers should not exist at all. This uncompromising viewpoint was trenchantly expressed when, in 1663, he was granted a monopoly of news publishing. The first issue of the re-launched

Intelligencer

contained the following statement of his journalistic philosophy:

Supposing the press to be in order, the people in their right wits, and news or no news to be the question, a Public Mercury should never have my vote, because I think it makes the multitude too familiar with the actions and counsels of their superiors, too pragmatical and censorious, and gives them not only an itch but a kind of colourable right and license to be meddling with the government.

These, though, were not normal times. If a paper were necessary, at least it could be put to good use, for nothing, at this instant, ‘more imports his Majesty's service and the public, than to redeem the public from their former mistakes’.

24

Muddiman was initially retained on a salary to assist in the production of the new paper, but working for L'Estrange could hardly have been a pleasure. More and more of Muddiman's energies were instead devoted to the production of a manuscript newsletter, which he provided as a confidential service for favoured clients and public officials. For this purpose he was attached to the office of the Secretary of State, where his operation fell under the wistful gaze of an ambitious young under-secretary, Joseph Williamson. Williamson saw in the exploitation of the official communications flowing into the Secretary's office the chance to place himself at the heart of the news operation. But first he had to remove L'Estrange. The opportunity arose in 1665,

when plague drove the court, accompanied by Williamson and Muddiman, to the sanctuary of Oxford. Marooned in London and shorn of his professional assistant, L'Estrange's incompetence as a newsman was laid bare. Williamson easily persuaded his superiors to strip L'Estrange of his publishing responsibilities in return for a generous pension. His news publications would be shut down, to be replaced by a single official paper: the

Oxford

, later

The

London

Gazette

.

25

11.2

The London Gazette

.

For the next fourteen years the

Gazette

would be the only paper published in England. Williamson's concept drew on several contemporary and historical models: Nedham's monopoly of news under Cromwell was one; the Paris

Gazette

was the obvious source of the title. But in contrast to these two,

The London

Gazette

was not published in pamphlet form; instead it reverted to the broadsheet style of the earliest Dutch papers. From its first issue the

Gazette

would be a single sheet, printed front and back, with the text in two columns.

And whereas the Paris paper was a private monopoly,

The London

Gazette

would be edited from within the office of the Secretaries of State, its text chosen from incoming newsletters and foreign newspapers. The actual editorial work was performed by civil servants, often quite junior members of the Secretary's staff. Williamson and Muddiman, meanwhile, devoted themselves to their real prize: the confidential manuscript news.

26

The London

Gazette

was therefore a curious sort of newspaper. It quickly developed a wide circulation, its twice-weekly issues (sold for one penny) snapped up by the inhabitants of the news-hungry capital. In principle it should have been well informed and authoritative. Its editors sat at the centre of a considerable network of information. Their office received regular reports both from agents abroad (including consuls settled in many strategic ports) and from correspondents all over England. But very little of this domestic news appeared in the

Gazette

. This was a quite conscious policy of Williamson and Muddiman. To an extent they shared the prejudices of L'Estrange, that the public should not be kept abreast of public matters. One of the first acts of the new regime had been to decree that the votes of the House of Commons should no longer be reported. This was a touchstone issue for proponents and critics of a free press in England and in consequence a reliable barometer of attitudes towards public opinion. The

Gazette

was therefore largely filled with foreign news, in the best tradition of its Paris cognate, and the early corantos. Domestic news was kept for the confidential newsletters, circulated to a carefully defined circle of public officials: the county lieutenants, postmasters and members of the Privy Council. In return for a free copy the postmasters and customs officials were required to write regularly with their own news.

27

Other recipients paid a subscription, which underwrote the costs of the copy office.

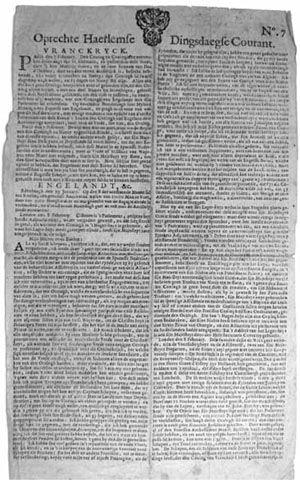

The official manuscript newsletters were also sent to select newsmen abroad in return for their news services. They used the English news contained in the newsletters for the basis of their newspapers, with the rather bizarre result that the readers of a Dutch newspaper like the

Oprechte Haerlemse Dingsdaegse Courant

could read more English domestic news than was available to English subscribers of

The London

Gazette

.

The

Gazette

, in this way, provided its readers with a very partial view of affairs, mostly confined to foreign news. But its sources of information were very good: text was abstracted from a range of continental newspapers and the manuscript news-books provided by continental newsmen as part of their exchange agreement. The

Gazette

was therefore reliable, and as informative as the government wished it to be. But apart from official communications, a reprinted proclamation or court circular, it said little or nothing about the pulsating politics of the day.

11.3

Oprechte Haerlemse Dingsdaegse Courant

. As this issue reveals, its readers would have been very well informed about English domestic politics.

Coffee

The public enthusiasm that had greeted the Restoration turned to discontent with remarkable rapidity. Twice in rapid succession England found itself back at war with the Dutch. The Second Dutch War, between 1665 and 1667, led to a ragged and humiliating defeat; the Third, from 1672 to 1674, raised widespread public unease at Charles II's alliance with Louis XIV against a fellow Protestant nation. Public anxiety focused increasingly on the king's brother James, Duke of York; his evasive and truculent response to the Test Act in 1673 confirmed what the political nation had long suspected: that the heir to the throne was a Catholic. The political crisis was brought to a head in 1678 when the murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, a firm Parliamentary defender of Protestantism, seemed to lend some plausibility to shocking allegations of a Popish plot to assassinate Charles and install James in his stead.

28

The Godfrey murder made a popular hero of Titus Oates, the opportunist charlatan who had first concocted the plot. Parliament now brought forward a formal bill to exclude James from the succession. Rather than allow this, Charles first prorogued, then dissolved Parliament altogether.