The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (41 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

In this respect the political broadsheets make a psychologically complex contribution to the media of news: never in the front line of criticism, always cheering from a safe distance. Whereas pamphleteers often took risks to espouse a cause, political broadsheets liked nothing more than to pummel a political figure already destroyed by events; and that, judging by the evidence of the broadsheets’ popularity, also appears to have coincided with the preferences of their readers.

The Dam Bursts

If the first rule of politics is that you should be lucky in your enemies, then nowhere was this more triumphantly vindicated than for the initially small band who found themselves in opposition to the Stuart kings of England. While James VI of Scotland had been grudgingly accepted as the least bad solution to the question of succession after the death of Queen Elizabeth, his son Charles was almost preternaturally devoid of political skill. From his

search for a Catholic wife to his assault on the traditions of Parliament and the Church of England, the policies of Charles I seemed designed to coalesce a truculent but generally obedient people into defiance. A man whose idea of public relations was to commission a new portrait by Van Dyck, Charles naturally totally missed the significance of the new news media. First he confirmed the right to produce newspapers as a monopoly; then he banned them altogether; then he restored them just in time (1638) for them to be a pillar of the opposition gathering against him.

37

Since the king also punctiliously upheld the prerogatives of the Stationers’ Company of London against provincial interlopers, he also ensured that his rebellious capital would start the war with a near monopoly of the printed word.

In England the Civil Wars marked a long-delayed coming of age for the printing industry. For much of the sixteenth century the market was simply too small to sustain more than a modest and rather conservative range of titles, particularly as English readers continued to look to European imports for scholarly books in Latin. English printers were tied to the vernacular trade and dependent on the Crown for much of their work; the industry was almost entirely confined to London. Although Londoners shared in the general European thirst for news, much of it initially came in the form of translations of pamphlets first published in French or Dutch. In the 1620s London joined the European fashion for weekly news-sheets, and manuscript news services established a foothold. But it was only in the 1640s that the English press came into its own.

If Butter and Bourne imagined that the restoration of their corantos monopoly in 1638 would recover their fortunes, they were to be disappointed. Events had moved on. Their diet of despatches from the continental wars no longer met the public's expectations: readers had more urgent domestic concerns. The attempt to impose an Anglican settlement on the reluctant Scots brought the first armed confrontation and further isolated King Charles from a perplexed and anxious political nation. In 1640 all eyes were on Westminster, where the king's reluctant recall of Parliament catalysed the nation's discontents. The urgency of constitutional debate led to the production of a new type of serial publication, the rather misleadingly entitled ‘diurnal’ (or daily). These offered a weekly summary of events in Parliament with an account of each day's business. These diurnals were circulating in manuscript throughout 1640, but it was only in November 1641 that the first was published as a printed serial newsletter.

38

The diurnals struck an immediate chord with the reading public, and by the end of 1642 more than twenty independent publications had been published using

Diurnal

, or some variation, in their title.

39

The most successful and enduring was the

Perfect Diurnall

of the passages in Parliament

of Samuel Pecke, an experienced editor of manuscript news-sheets and a pioneer of the new trend towards domestic news.

This resumption of serial news was significant, but not a major constituent cause of the unfolding political drama. The diurnals appeared in print only towards the end of 1641, the year that put the conflict between king and Parliament beyond peaceful resolution. Here, as in earlier conflicts, it was pamphlets that drove forward the political debate. The decisive years before the outbreak of the Civil War were accompanied by a torrent of publications. The output of the press grew almost fourfold between 1639 and 1641, and reached its peak in 1642 with almost four thousand published works.

40

Most of this increase can be accounted for by political pamphlets. We can chart the dramatic events of the crisis of 1641 through successive pamphlet surges: the trial of the Earl of Strafford; the attack on Archbishop Laud; the fear of Catholic plots.

41

The Irish rebellion stimulated a rash of hard-hitting publications, some with illustrations graphically describing the torments suffered by the Protestant settlers.

42

The feverish, vituperative tone of this literature reached new heights, for England at least. The pitiless hatred directed towards Strafford and Laud, the gloating descriptions of Strafford's descent into Hell, were matched by an increasingly martial tone in the calls for the defence of true religion. Though the fighting was only irrevocably joined when the armies squared up at Edgehill in 1642, the shedding of blood had been eagerly anticipated many times over in the angry, vengeful and virulently sectarian pamphlets of the previous year.

In contrast to the tone of the pamphlet literature, the diurnals may seem rather staid and cautious; nevertheless they represent a quiet revolution in the European news world.

43

For this was the first time that regular serial publications had been devoted primarily to domestic events. Secure in their command of England's only substantial print centre, Parliament embarked on a conscious effort to engage the political nation. Parliamentarians had imbibed the insight of Paolo Sarpi, that the informed subject ‘gradually begins to judge the prince's actions’, but had drawn the opposite conclusion: that this was desirable. In the years to come, Parliament would make conscious and effective use of its command of the London press, ensuring that its acts and proclamations were known in all parts of the kingdom under its military control.

44

For royalists this posed a challenge almost as daunting as the military conflict. Having withdrawn from his rebellious capital in January 1642, Charles I finally recognised that a more active policy of public engagement was necessary if he was to challenge the overwhelmingly hostile use of print. The establishment of a press in cities loyal to the king did something to redress the balance, leading in 1643 to the foundation of a weekly news journal devoted explicitly to the royalist cause: the

Mercurius Aulicus

.

This, again, was an important moment in the history of newspapers: the beginnings of advocacy journalism.

45

To this point the periodical press had struggled to demonstrate its relevance to the conflict. Although 1642 had seen a rash of new titles, most had ceased publication by the end of the year. This set the pattern for the period as a whole. More than three hundred ostensibly serial publications were founded between 1641 and 1655, but the vast majority (84 per cent) published only one issue, or a handful of issues.

46

This makes the point that contrary to what we might imagine from this great burst of creative energy, these were not optimum conditions for the publication of newspapers. Papers needed stability: to build a subscription list it was always best to avoid giving offence, which risks providing the authorities with a pretext to close the publication down. This was hardly the temper of the times in these turbulent decades. News serials, with the address of the seller prominently displayed, were sitting ducks for retribution. Pamphlets, on the other hand, could be published anonymously, and increasing numbers were.

The

Mercurius Aulicus

was very different.

47

It offered a serial commentary on events, abandoning the clipped sequence of brief reports characteristic of news reporting to this point in favour of longer essays scorning and goading the king's enemies. The ammunition for many of its articles was drawn from other news-books. When it came to the actual reporting of events the journal frequently fell short. The calamitous royalist defeat at Marston Moor, which opened the way for Parliament's eventual military triumph, was first reported as a victory: ‘Great newes’ from York proclaimed the

Mercurius Aulicus

in its issue of 6 July 1644. It had received ‘certain intelligence that the rebels are absolutely routed’. The following week it was forced into a humiliating retraction, albeit with the grumpy accusation that the Parliamentarians had deliberately held back the true report.

48

At another level, though, the

Mercurius Aulicus

was very successful. It certainly did a great deal to stiffen the sinews of the king's supporters, and irritate his enemies. When a consignment of five hundred copies was intercepted by Parliamentary forces, this was reported almost like a military victory. In the summer of 1643 Parliament set up its own advocacy serial, the

Mercurius Britanicus

, explicitly to counter the influence of

Mercurius Aulicus

.

49

This journal also had the distinction of launching one of the seventeenth century's most remarkable journalistic careers.

Marchamont Nedham was a naturally gifted writer.

50

His combination of impassioned advocacy, biting wit and an easy, flowing literary style was exactly right for these troubled times. For successive issues he went head to head with

Mercurius Aulicus

and landed some heavy blows. A natural risk-taker, Nedham was bold and outspoken, and occasionally he strayed over the

limits of what was permissible even in this extraordinary period. In 1645, after the king's defeat at Naseby, he fabricated a jocular ‘Wanted’ notice which made a crude reference to Charles's stutter.

51

Parliament took action, sending both the printer and the censor, who should have spotted this, to prison. Nedham was let off with a reprimand, a clear recognition of how valuable he was perceived to be to the Parliamentary cause. The

Mercurius Britanicus

was soon back in business, having missed only a single issue.

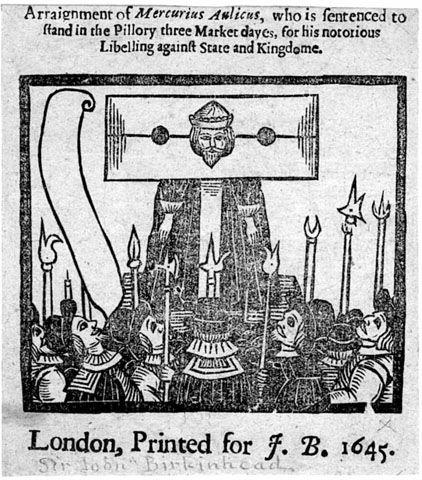

10.4 The arraignment of

Mercurius Aulicus

. This piece of Parliamentary wish fulfilment, with Sir John Birkenhead in the pillory, demonstrated the extent to which the king's propaganda vehicle had hit home.

This incident may have given Nedham too elevated a sense of his own importance, because the following year he was in trouble again, this time for an editorial describing Charles as a tyrant. He went to prison, but incarcerating Nedham for a symbolic fortnight did not have the desired effect. Tiring of his old employers, Nedham now made his apologies not to Parliament, but to the king; and Charles, incredibly, hired him to write for royalist publications. In the well-named

Mercurius Pragmaticus

, this versatile journalist now denounced Parliament and its Scottish allies for their conspiracy against the monarchy, and excoriated those pressing towards the rebellion's astonishing conclusion: the trial and execution of the king.

52

The execution of King Charles I in January 1649 sent shock waves around the European news world. The reading publics of Germany, Holland and France were fascinated that the new citizen masters of England could bring their quarrels to such a conclusion. Continental readers hungered after details

and explanations.

53

Pamphlets and above all illustrations of the execution were printed and reprinted in many countries.

54

In England itself the situation was very different. The century's most extraordinary news event produced a comparatively subdued response. This was partly because the defenders of England's ancient liberties ensured that this should be so. In February the House of Commons, reduced to a Rump by Pride's Purge of the previous year, responded furiously to pamphlets distancing their previous Presbyterian allies from the execution. An Act for the better regulation of printing imposed draconian financial penalties on those who ‘shall presume to make, write, print, publish, sell or utter, or cause to be made, printed or uttered, any scandalous or libelous books, pamphlets, papers or pictures whatsoever’. Such regulations were not new: Parliament had already passed censorship measures in 1642, 1643 and 1647.

55

What is most striking is the new emphasis on regulating visual imagery, no doubt inspired by the awareness that there was no more striking image than that of a decapitated king. What Parliament could not control was the extraordinary popularity of the

Eikon basilike. The pourtraicture of his sacred majestie in his solitudes and sufferings.

56

This purported to be the king's own account of events since 1640, interspersed with his prayers and meditations. It was a publishing sensation, with thirty-five English and twenty-five continental editions in its first year alone. At last, if rather too late, the Royalists had discovered the secret of successful propaganda.