The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (5 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Problems of this nature apply even to those at the very apex of medieval Europe's emerging news networks. The Cistercian monk Bernard of Clairvaux, for example, was one of the most distinguished voices of medieval Christianity. He was deeply involved in the major political and theological controversies of his day. He spoke out against the Cathars and the theologian Peter Abelard; he intervened freely in disputes over the election of bishops, and offered his counsels to the French king, Louis VI. Between 1146 and 1147 he preached passionately in favour of the Second Crusade. All of this required close attention to the maintenance of an active network of information, messengers and correspondence.

In the conditions of twelfth-century Europe this was by no means easy, but Bernard possessed one priceless advantage. As Abbot of Clairvaux, the mother house of an extensive network of monasteries, Bernard could call upon the assistance of a willing band of peripatetic and literate churchmen. A remarkable number of Bernard's letters survive – around five hundred – far more than for his contemporary (and rival) Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny.

8

These were just the visible remains of an information network that extended far beyond regular communications with Rome, even as far as Constantinople

and Jerusalem. The maintenance of such a network was not without its challenges. As was the case with Roman couriers, the written communication was often little more than a letter of introduction, with the substance of the message intended to be conveyed verbally. Bernard would sometimes have to wait patiently for a suitable envoy who could be trusted to deliver a sensitive communication accurately. He was lucky that Clairvaux was a regular stopping place for numerous pilgrims and clerics on official business, situated as it was in prosperous Champagne, between Paris, Dijon and the Alpine passes.

Bernard was, by the standards of the time, exceptionally well informed. But there was still a large element of chance in the individuals who passed by and the news they brought. It was seldom possible to corroborate a report brought by a visitor – Bernard would have to make his own estimate of the reliability of the source. Many of those who brought news – of a disputed episcopal election, for instance – had their own axes to grind. If the news was important enough for Bernard to send his own messenger, it might be many months before he received a reply. Even a journey back and forth to Rome, the hub of Europe's most intensive traffic in information, might take up to four months, as the messenger inevitably had his own business to conduct, and might not be planning a return trip to Clairvaux. Contact with more occasional correspondents was even more sporadic. A complex negotiation, which required the passage back and forth of several despatches, was hard to envisage.

Chronicles

Bernard of Clairvaux was an exceptional figure: a true prince of the Church. But the wish to stay abreast of events, and an awareness of the significance of life outside the cloister, was shared by many of his fellow clerics. Medieval monasteries served an important function as custodians of the collective social memory: monks were the first historians of western Christendom. To perform this function required that they make assiduous efforts to gather information on the world's follies and travails; in the words of the chronicler Gervais of Canterbury, ‘such deeds of kings and princes as occurred at those times, along with other events, portents and miracles’.

9

Some of these events had a decidedly contemporary character, and this trend becomes far more pronounced in the chronicle-writing of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This development was partly the consequence of the increasing predominance of chroniclers who were secular priests and even laymen, many with close access to the centres of power in the royal courts. The monastic chroniclers in contrast had, by nature of their vocation, been largely confined to their own houses. These new chroniclers could get

out and about: they frequently wrote from their own experience, or recorded having personally spoken to eyewitnesses or participants.

These medieval chroniclers offer a precocious and unexpected sense of developing news values. Naturally they write from a religious perspective: events reflect the unfolding of God's purpose and must be interpreted within the context of divine revelation. But the chroniclers also reveal a profound concern that the events they record should be credible and recognised as such. They offer repeated testimonials to the quality of their sources, the social status or number of the witnesses, and whether the writers were personally present. Even the recording of distant events reflects a clear concern to report only what was credible. Thus the chronicler of St Paul's Cathedral in London recorded, of an exceptionally severe frost in Avignon in 1325 in which many froze to death, that ‘according to the testimony of those who were there and who saw it, for one day and night the ice covering the Rhône, which is an extremely fast-flowing river, was more than eight feet thick’.

10

Note how the addition of a seemingly precise but unverifiable detail, the thickness of the ice, adds greatly to the credibility of the account.

Many medieval chroniclers were partisan – fierce critics or passionate supporters of the kings whose deeds they record. But they also exhibit a pre-cocious instinct for the ethics of news reporting. If they rely on second- or third-hand accounts, these are identified as such: ‘so it is said’, ‘so people said’ (

ut fertur; ut dicebantur

). When they know of conflicting accounts they are often scrupulous in reporting this fact. Of course chronicles are written with the benefit of hindsight, when events have been resolved; this was reporting without any of the hazards of contemporaneity. The chroniclers were able to look back and draw the appropriate morals: that a comet had portended great evil, that a king had been rewarded for his virtue or laid low by his vices. News was never fleeting or ephemeral, but always imbued with purpose. This form of moralising was equally characteristic of much of the news reporting of the following centuries, as we shall see. In this and so many other respects the medieval chroniclers’ views of contemporary history would prove profoundly influential in the development of a commercial news market. They reflected a shared vision of the continuum of history, linking past, present and future events in one organic whole.

The Pilgrim Way

Medieval travel was never undertaken without purpose. The hardships and dangers of the road were well known, and there were few with the resources or leisure to undertake journeys not directly connected to their occupational

needs. A traveller passing through a town or village on the road, if he was not one of the traders who plied that route, was likely to be either a pilgrim or a fighting man. Pilgrims often traded conversation for charity. Sometimes they could be persuaded to carry letters or messages to an intermediate destination. Few would have approached a band of armed soldiers for a similar favour.

For large parts of the high Middle Ages the eyes of both groups were turned towards Palestine. The mustering of crusader armies were major public events from the eleventh to thirteen centuries. Calls to arms and for pious donations to underwrite the costs of the Crusades reverberated around Europe. Many of Europe's citizens would have known someone who had joined the holy hosts, and returning knights and camp-followers brought their own accounts of these strange and unforgiving lands. Jerusalem was the ultimate test of pilgrim devotion, the more so because after the fall of Acre in 1291 the holy sites were never again in Christian hands.

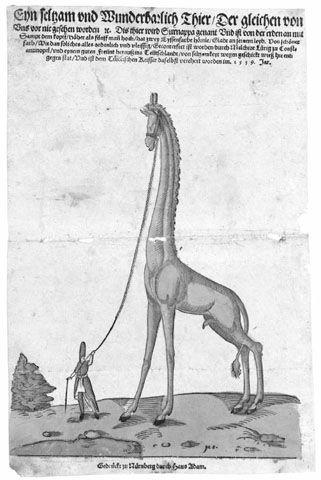

Those setting off on these arduous journeys could, in the centuries that followed, avail themselves of a quite considerable body of travel literature offering routes and a tour of the sacred places. By the fourteenth century such travelogues offered a wealth of observation on local customs and exotic beasts (travellers were particularly amazed by the giraffe).

11

The time such written guides took to filter through to a wider public undermines their claims to be news publications – this was a time, remember, when each book had to be laboriously copied by hand. But they do mark the first stage of a certain broadening of horizons, and an expansion of the geographical frame of reference, which will be one of the key aspects of news culture in the centuries that follow.

The Crusades must certainly have impacted on most communities in the western countries where the crusader armies were recruited. In a society where speech was still the main means of delivering facts, people were eager to hear tales of faraway places. In the eleventh century, it has been said, an ordinary Christian would likely have been more familiar with the existence of Jerusalem than the name of their nearest big city.

12

But this came at a price. By inflaming Christian opinion against Islam, the seemingly endless Crusades canonised a series of lurid stereotypes that proved remarkably enduring. Even the most anthropological pilgrim narratives of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries seem to have had little impact in challenging the exotic fantasies of Islamic society that resonated through the literature of the period. If Christian society knew anything of the Saracens, it would have been from the popular epic poems of the

Chansons de geste

, rather than eyewitness accounts.

This created a challenging environment for the reception of news. Throughout the medieval period and into the sixteenth century, news, especially news of faraway events, had to compete with marvels, horrors and deeds

of valour related in the travelogues and romantic epics.

13

The truth was often more prosaic, and therefore vastly less entertaining. Telling truth from fiction was never easy. Even if we confine ourselves to literature that purported to be factual, none of the pilgrim writings enjoyed a shadow of the success of Marco Polo's accounts of more distant lands, or the even more spurious

Travels

of John de Mandeville. These two works survive from the medieval period in more than five hundred manuscripts.

14

Both lived on to populate the imagination of Renaissance travellers including, most influentially, Christopher Columbus.

Faith and Commerce

Not all pilgrimages were as arduous as a trip to the Holy Land. The majority of those undertaken, particularly by laypeople, were to local destinations. Geoffrey Chaucer's pilgrims, we may remember, made the relatively simple trip from Southwark to Canterbury, a journey of about 60 miles. Since this was along one of England's best established and well-maintained roads, one wonders how they had time for more than two or three stories. Of course the leisured circumstances of Chaucer's pilgrims and the undemanding nature of their journey are part of the joke.

By this point the rage for pilgrimage was already attracting a degree of criticism from more austere religious, who feared pilgrims like these might act as a distraction for the more pious and aesthetic. The distinguished theologian Jacques de Vitry was one who had scathing things to say about ‘light-minded and inquisitive persons going on pilgrimages not out of devotion, but out of mere curiosity and a love of novelty’.

15

Nevertheless Chaucer does encapsulate very effectively the opportunities that pilgrimage provided for conviviality, gossip and the exchange of news.

In the later Middle Ages pilgrimage was part of the intricate fabric of church life. Canterbury was one of a number of locations that attracted both English worshippers and pilgrims from farther afield. France had a proliferation of medieval pilgrimage sites including Limoges, Poitiers and Bourges.

16

The more austere locations included St Andrews in Scotland and Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain, though many pilgrims to Santiago went by boat, rather than enduring the long trek overland. Competition between pilgrimage sites was intense, not least because local rulers were very aware of the monetary benefit of receiving pilgrims and the attendant sales of trinkets and souvenirs. The extent of this commerce, and by implication the number of pilgrims criss-crossing Europe's roads, can be judged by the fact that an enterprising German entrepreneur entered into a contract to provide 32,000 pilgrims’ mirrors for the septennial display of holy relics in Aachen in 1440.

17

It was only the failure of this enterprise (the partners had mistaken the year, and could not repay their loans in the stipulated term) that caused the projector, one Johannes Gutenberg, to redirect his energies towards a different experimental commercial technology: the printing press.

1.3

A rare and unusual animal

: the giraffe. It is easy to see why so many, to us impossible, travellers' tales were believed, when something as implausible as the giraffe turned out to be true.