The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (67 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

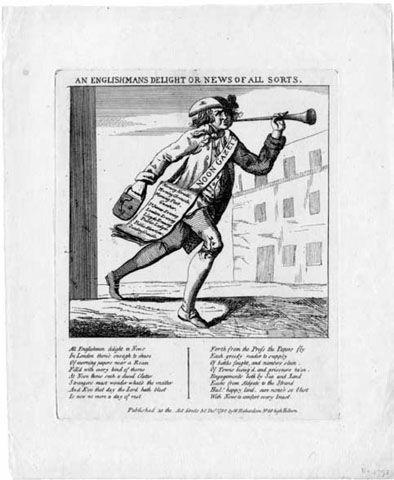

The sense of unlimited possibilities is palpable, and it captures very well a strand of commentary that continued through the nineteenth century. This would be a great age of newspaper triumphalism. By 1835 an American commentator (naturally a journalist) could ask: ‘What is to prevent a daily newspaper from being made the greatest organ of social life?’ ‘Books have had their day – theatres have had their day – religion has had its day …. A newspaper can be made to take the lead in all these great moments of human thought.’

3

This was heady stuff. One can see why the French Revolution, which witnessed the sudden, tumultuous emergence of a voracious press, should have made such an impact on contemporaries. In France the contrast between the controlled press of the Ancien Régime and the freedom of the revolutionary years was particularly stark. But even in their own terms the claims made for the press were somewhat overblown. Was the press really more important than the agitation on the streets, the debates in the National Assembly, or the heated discussions in the Jacobin Club that, for instance, sealed Danton's fate? The Terror was underpinned by Robespierre's control of the Committee of Public Safety, a body of no more than a dozen people.

In this triumphant praise of the periodical press we see strong echoes of the salutations that accompanied the birth of printing in the mid-fifteenth century, and intermittently ever since. Print was widely celebrated by scholars and printers, themselves heavily involved in the new industry, for its transformative role in society. Looking back we can see in those wide-eyed encomia to progress a great deal of false prophecy and rationalised self-interest. It reminds us that of all the technological innovations of that busy era, print was unique in its capacity for self-advertisement. Guns, sailing ships and improvements in navigation were all critical to the European domination of the non-European world, but none could hymn their own achievements in quite the same way.

All of this helps explain why, since the history of news first came to be written, the development of the newspaper has traditionally taken centre stage. The first systematic histories of news were all written during a period when the newspaper was not only the dominant form of news delivery, but appeared likely to remain so. The history of news was to a very large extent, at least before the advent of television, the history of newspapers. The period before the invention of the newspaper is reduced to the status of pre-history.

Now, as we re-enter a multi-media environment in which the future of newspapers looks decidedly uncertain, we can take a rather different perspective. As the first chapters of this book have demonstrated, there was plenty of scope for the circulation of news before newspapers, indeed, before the invention of

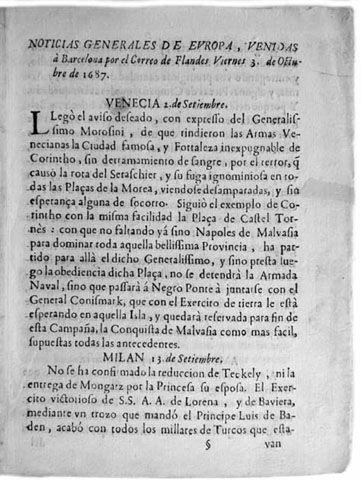

printing. When newspapers made their appearance their progress was halting and uncertain. From the first (and at the time widely celebrated) experiments with a periodical press at the beginning of the seventeenth century, to the decisive breakthrough at the end of the eighteenth, would be a full two hundred years. Even during this time, a period of rapid expansion for the European economy in every way conducive to the development of an ever more sophisticated news market, the coverage of the periodical press was decidedly patchy. Spain lagged a long way behind developments in other countries, and this was also true of Italy, which had been until the end of the sixteenth century the very heart of the world's news market. Rome had no newspaper before the eighteenth century; here, the manuscript newsletters remained at the heart of the city's vibrant marketplace of news.

4

In Spain, even the traditional leaders of society pursued their power struggles by paying for the publication of broadsheet libels that could then be distributed on the streets.

5

It would not be until the mid-nineteenth century that newspapers established a relatively full coverage in all parts of western Europe.

Why was the advance of the newspaper not more rapid? One reason, it is clear, is that the periodical press was attempting to make its way in a complex communications environment, where news was already disseminated relatively effectively in a large variety of ways, by word of mouth, letter, non-serial print, proclamations, pamphlets and so on. To many consumers newspapers did not seem much of an advance on these well-established conduits of news: indeed, in some respects they represented a retrograde step. To drive this point home we only need to look at what have traditionally been regarded as the defining characteristics of periodical news: periodicity and regularity; contemporaneity; miscellany (presenting many different strands of news) and affordability. We can see that what scholars have described as important advances all had drawbacks when seen through the eyes of contemporary consumers.

First, periodicity. We have seen that the idea of a newspaper, a gather-up of the week's news from many parts of Europe that could be delivered economically to subscribers, initially appeared very attractive. It offered a window onto a sophisticated world of politics and high society previously closed to all but the few. At first it was rather gratifying to be initiated into the complex, exotic world of court life and international diplomacy; but with time it became rather wearing. The constant enumeration of diplomatic manoeuvres, arrivals and departures at court and military campaigns could be repetitive and increasingly mundane: particularly as the significance of these events, if not immediately apparent, was never explained. The apparent virtue of a newspaper, its regularity, became something of a burden.

18.1 An early issue of a Spanish paper. Despite almost a century since the first newspaper in Germany, the style is still very rudimentary.

This was not just a new way of reading the news. To many it involved a total redefinition of the concept of news. Most of those who had followed the news to this point would have done so irregularly. When news piqued their interest they could purchase a pamphlet; they were most likely to do so when, for one reason or other, they felt personally touched by events. Now with the newspapers they were offered an undigested and unexplained miscellany of things that scarcely seemed to concern them at all. Much of it must have been completely baffling.

The extent of this transformation appears more starkly if we look a little more closely at the pamphlets that bore the main burden of reporting contemporary events in the first age of print. Reading these works we get a vivid sense of our ancestors’ fascination with the extraordinary. News pamphlets are filled with disasters, weather catastrophes, heavenly apparitions, strange beasts, battles won, shocking crimes discovered and punished. In contrast, much of

what was reported in the newspapers was necessarily routine and unresolved: ships arrive in port, dignitaries arrive at court, share prices rise and fall, generals are appointed and relieved of command. This might have been critical information for those in the circles of power and commerce, but for occasional news readers there was nothing to compare with the sighting of a dragon in Sussex.

6

Pamphlets and news broadsheets allowed the discerning reader to dip in and out of the news as they chose. They also reflected accurately one great truth inimical to the periodical press: that news was actually more urgent at some times than others. Two centuries of regular daily papers and news bulletins have trained us out of an appreciation of this. Yet when we turn on a news bulletin and hear, as the first item, that a committee of legislators has reported that some government activity could be accomplished a little bit better, then perhaps we may conclude that our ancestors had a point.

So it is with the other great ‘advances’ introduced with the newspapers. The contemporaneity of newspapers, a recital of the latest despatches from nine or ten of Europe's capitals, represented an abandonment of the customary narrative structure of news. A pamphlet would most usually describe a single event from beginning to end. It would be conditioned by knowledge of how matters had concluded – who had won a battle or how many had died in an earthquake. It could offer proximate causes, explanations and draw lessons. The newspapers in contrast offered what must have seemed like random pieces from a jigsaw, and an incomplete jigsaw at that. Even for regular subscribers there was no guarantee that the outcome of events described would be reported in the following issues. There was no way that editors could know which of the strands of the information reported from Cologne or Vienna would turn out to be important. And they had no way to pursue stories independent of the manuscript newsletters and foreign newspapers from which they constructed their copy: they could not contact their own correspondent in those places, because they did not yet have one.

Confronted with this miscellany of brief reports from Europe's news centres, newspaper readers were offered little help in finding their way to the news of most critical importance. Newspapers had not yet developed the design sophistication, or editorial capacity, to point up the most important stories, or lead their readers into understanding. Because verbatim reports and despatches were regarded as inherently more truthful, newspapers tended to avoid interpolations that would actually have assisted their readers in following the news. This form of editorial guidance was far more likely to be found in pamphlets. As for affordability, in the case of periodicals this was often more apparent than real. Although an individual copy of a newspaper might only

cost a couple of pence, a regular subscription represented a more substantial investment. It also required the development of a considerable infrastructure on the part of the publisher so that copies could be delivered to their readers.

All of this helps explain how, despite the undoubted interest in the concept of a newspaper, so many news serials failed; or only succeeded with official subsidy. It is also no surprise that the periodical press flourished most in periods of high political excitement (when of course pamphlet production also rose substantially).

All of this prompts the question why, if newspapers were so testing to new readers, they did finally become an established (and then ultimately a dominant) part of the news infrastructure. Given how indigestible were their contents, we may conclude that the newspapers succeeded partly because of what they represented, rather than what they contained. For the first time the reading public was offered news of a type, and in a form, that had previously only been available to those in the circles of power. If their newspaper was a peepshow, it was a peepshow of the most flattering sort. Even if a country squire in Somerset or a physician in Montpellier had no particular interest in a dynastic crisis in Muscovy, merely to have access to such intelligence conveyed status. Newspapers were a non-essential purchase for those with a degree of disposable income, and it helped that the number of people in this position increased very rapidly in this era. A consumer society is driven as much by fashion as by utility, and in the eighteenth century a newspaper became an important accoutrement of polite society.

Towards the end of this period the newspaper also gained traction by throwing off many of the chaste virtues that had characterised its first century. Here the gradual expansion into the reporting of domestic news was absolutely decisive. This occurred at very different times in different parts of Europe. The competitive and vibrant London news market was unusually precocious in plunging so boldly into the contentious partisan politics of the early eighteenth century. Elsewhere, the development of domestic news reporting was essentially a feature only of the last years of the eighteenth century, and in some places even later.

This undoubtedly made newspapers interesting to an expanding public, who were encouraged to believe that they too could play an informed and active role in political discussion. The arrival, with the great crises of the late eighteenth century, of advocacy journalism also finally dissolved the distinction between news and opinion, and between the newspaper and other forms of writing on current affairs: pamphlets of course, but also the new, and highly respected, political journals. This transformation was not universal; the tradition of political neutrality lived on in many places where a single paper served

a local market, and had no wish to alienate a portion of its readers. But the effect was, nonetheless, profound and enduring.