The Judgment of Paris (13 page)

After Waterloo, the young prince, then age seven, was exiled with his mother to a castle in Switzerland, where they were put under the surveillance of the British, French, Austrian, Russian and Prussian ambassadors. This exile was to last for many years, during which time the sickly child became a vigorous young man who fought by the side of Italian revolutionaries in Rome and conducted multiple love affairs in Switzerland. In London, working in the British Museum, he penned a political treatise,

Ideas of Napoléon-ism,

which he published in 1839. These musings were no idle occupation, for in 1832 the possibility of the young prince fulfilling the prediction of his horoscope and seizing the French throne had unexpectedly presented itself. Napoléon's only legitimate son, the Due de Reichstadt—the so-called Napoléon II—died of tuberculosis in Vienna, leaving Louis-Napoléon as the dynastic heir.

*

He duly set about making plans to oust King Louis-Philippe, but an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1836 ended with his arrest, imprisonment and then another exile as he was sent to America aboard a French warship. In New York City he proved a great social success, meeting Washington Irving and impressing the locals with his wax-tipped mustache, a sight virtually unknown in America.

Four years later, in August 1840, Louis-Napoléon made a second attempt to reclaim what he regarded as his birthright. By this time he was living in London, in a mansion in Carlton Gardens staffed by seventeen fervent Bona-partists. In a daring bit of bluff, he and his band of fifty-six conspirators—his domestic servants among them—donned military uniforms, chartered a Thames pleasure boat named the

Edinburgh Castle,

and made for the French coast. On board were nine horses, two carriages, several crates of wine, and a tame vulture bought at Gravesend to improvise as an eagle, the totem of the Bonaparte family. This ragtag expeditionary force landed at Boulogne-sur-Mer but beat a hasty retreat when the presence on French soil of the Bonaparte heir failed to incite a popular uprising against the King. When the landing craft capsized in the Channel, the invasion ended with Louis-Napoléon clinging to a buoy and awaiting his rescue, which came in the form of the French National Guard. Fished from the waves, he was arrested and then sentenced to life imprisonment in the fortress at Ham, a medieval Château in northern France. There he spent the next six years. His confinement does not seem to have been onerous, since he found opportunities to author a treatise on sugar beets, hatch a scheme to dig a canal across Nicaragua, and carry on a liaison with a ginger-haired laundress named Alexandrine Vergeot, who ironed the uniforms of the prison's officers and lived in the gatekeeper's house. He gave her lessons in grammar and spelling; she returned the favor with two children, both of whom, confusingly, were named Alexandre-Louis.

Louis-Napoléon escaped from Ham in 1846 by donning the uniform of a workman and casually strolling through the front gate with a plank of wood balanced on his shoulder. He then returned to England, where he served briefly as a special constable at the Marlborough Street police station and dallied with his latest mistress, Lizzie Howard, the daughter of a Brighton bootmaiker. Soon, however, Louis-Napoléon's destiny drew nigh. His chance came in 1848, the "Year of Revolution," when an economic downturn and widespread crop failures, combined with demands for more liberal governments, triggered riots and revolutions across much of Europe. In February, following pitched battles in the streets of Paris, King Louis-Philippe abdicated his throne, fleeing to England as his Bonapartist rival crossed the Channel in the opposite direction. In December of that year, with a majority of four million votes, Louis-Napoléon was elected President of the Second Republic, and the former prisoner of Ham found himself enjoying the splendors of the Élysée Palace. Three years later, anticipating the end of his four-year term as President, he consolidated and increased his powers in a bloody coup d'etat. In an operation code-named "Rubicon," he dissolved the Constituent Assembly, imprisoned many of his opponents (including Adolphe Thiers), and sent the army into the streets of Paris, where 400 people were killed in violent skirmishes. One year later, on December 2, 1852, he proclaimed himself Emperor Napoléon III.

The Second Empire was one of the gaudiest and most vainglorious eras in the history of France. The years since Louis-Napoléon came to power had witnessed unprecedented economic expansion and commercial prosperity. Industry flourished, foreign trade tripled, household incomes increased by more than fifty percent, and credit grew with the establishment of new financial institutions. Grand projects were undertaken, such as the building of the new sewers and boulevards in Paris and the laying of thousands of miles of railway and telegraph lines. Louis-Napoléon was making the country live up to his vision of "Napoleonism," which, he had written, "is not an idea of war, but a social, industrial, commercial and humanitarian idea."

17

Louis-Napoléon may have disliked wars, but he had nonetheless involved France in the Crimean War, which ended in 1856, and in the war against Austria in Lombardy in 1859. The year 1859 also witnessed French military expeditions to Syria and Cochin-China, in the latter of which the Emperor's troops occupied the capital, Saigon. In the following year, French troops invaded Peking and burned the Summer Palace.

His swashbuckling career notwithstanding, Napoléon III was a less than prepossessing character. He looked, to Théophile Gautier, like "a ringmaster who has been sacked for getting drunk," while one of his generals claimed he had the appearance of a "melancholy parrot."

18

The urbane aristocrat Charles Greville, meeting him in London, found him "vulgar-looking, without the slightest resemblance to his imperial uncle."

19

In fact, the only thing that he seemed to have shared with Napoléon was a short stature: he was only 5 feet 5 inches tall. A reserved and thoughtful man with a waxed mustache, a pointed beard and hooded eyes, he possessed an air of inscrutability. It was said that he knew five languages and could be silent in all of them. Prince Richard von Metternich, the Austrian ambassador, called him the "Sphinx of the Tuileries."

20

But most of his opponents were guilty of underestimating his abilities, and by the 1860s he had become, as an English newspaper admitted, "the foremost man of all this world."

21

On April 22, in the midst of the judging controversy, Emperor Napoléon left the Palais des Tuileries, which sat beside the Louvre, for the short journey to the Palais des Champs-Élysées. Despite having been a popular target for assassination (in 1858, most notoriously, an Italian named Orsini had thrown three bombs at his carriage as he arrived at the opera for a performance of

William Tell),

he was accompanied only by a single equerry. Arriving at the exhibition hall, he demanded to be shown examples of both accepted and rejected works, some forty of which were duly exposed to him, in the absence of Nieuwerkerke and the jury, by the team of white-coated attendants.

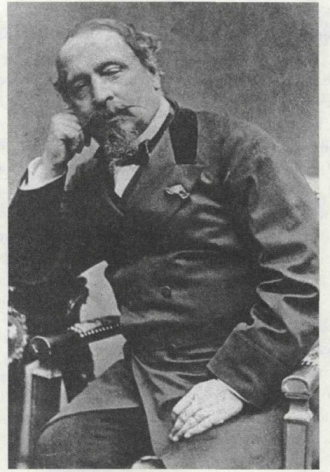

Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Napoléon III (Nadar)

His uncongenial reaction to Courbet's

Bathers

a decade earlier notwithstanding, Louis-Napoléon had virtually no interest in painting. One of his wife's ladies-in-waiting claimed that art was "a subject strangely foreign to his natural faculties."

22

And a good friend from his days in London, the Earl of Malmesbury, was shocked, during a visit to Paris in 1862, at his ignorance about even the most famous painters.

23

At the Palais des Champs-Élysées, however, the Emperor managed to sustain his interest and restrain his riding crop. For more issues were at stake, he knew, than simply the fortunes of a band of disgruntled artists.

Since his coup d'etat, Napoléon III had been, for all intents and purposes, the absolute ruler of France. He commanded both the Army and the Navy, and he alone could promulgate laws, declare wars and conclude treaties. He appointed all of his Ministers, who were accountable to him alone and not to the Legislative Assembly, a body (elected through universal male suffrage) that sat for only three months of the year.

*

This autocracy was sustained by a good deal of censorship and repression. Trial by jury had been eliminated, and under the Law of Général Security, passed in 1858, anyone suspected of plotting against the government could be arrested and deported without trial. The

Marseillaise

was banned (the Emperor did not want its patriotic strains stirring the blood of French republicans) and in fact singing songs of any sort was banned in all cafés and taverns, which faced closure if they threatened to become hotbeds of dissent. There was no freedom of assembly, and organizations perceived as hostile to the government were proscribed and suppressed. Nor, of course, was there any freedom of the press. So draconian were the restrictions on newspapers during the Second Empire that a satirical pamphlet reported that any journalist wanting to publish an article of any sort "should hand himself in to the authorities twenty-four hours in advance."

24

Images were likewise censored, since a law of 1852 required all prints to be submitted, before they could be sold or exhibited to the public, to the Dépôt Légal, where they were carefully scrutinized for subversive messages. Books, likewise, could not be published without a license from the police, and the works of many authors were outright banned. Among the proscribed writers was Victor Hugo, a former supporter of Louis-Napoléon who had turned against him and, in 1852, evaded arrest and fled to the island of Jersey, from where he derided the Emperor as a "disgusting dwarf."

The Emperor had been especially mindful of dissent in the spring of 1863, since he had called an election, the first in France for eight years, for the end of May. The Minister of the Interior, the Comte de Persigny—the prime strategist in Louis-Napoléon's two failed coup attempts

†

—was busy squelching the opposition press in the run-up to this election, in which the republicans in Paris, led by Adolphe Thiers, looked poised to increase the number of their seats in the Legislative Assembly. To make matters worse, this election would be fought against the background of an unpopular war in which the Emperor had embroiled himself in Mexico.

Louis-Napoléon had declared war on Mexico in 1862, seeking to remove from power the government of Benito Juárez, a popular lawyer and liberal reformer. A Zapotec Indian who had once worked in a cigar factory in New Orleans, Juárez had swiftly alienated Catholics in Europe, soon after coming to power in 1861, by confiscating Church lands and expelling monks and nuns from their convents. He further infuriated the European powers by suspending payment of Mexico's foreign debts, which, in the case of France, amounted to twenty million pesos. With America embroiled in its Civil War, the Emperor saw an opportunity and a reason to flex his muscles and invade the North American continent. Claiming that he was "rescuing a whole continent from anarchy and misery,"

25

he dispatched 3,000 French soldiers with orders to capture Mexico City and replace Juárez with a Catholic monarch. The French promptly suffered defeat at Puebla on May 5 (the famous "Cinco de Mayo"), a stunning rout that the French press were banned from reporting. Thirty thousand more troops were then shipped across the Atlantic. All of them had reached Mexican soil by early 1863, and in the middle of March Puebla, sixty-five miles from Mexico City, was again under siege. Even the Emperor's strongest supporters had doubts about the Mexican enterprise.

26

By the third week in April, Louis-Napoléon was anxious for news to pacify his critics and trumpet a French victory before the election.

The man who visited the Palais des Champs-Élysées on April 22 was thus, despite his wide-ranging powers, not invulnerable. Nor was he deaf to protests and complaints. Despite the absolutist nature of his regime, he was keenly attentive to public opinion, knowing that his authority ultimately rested not on the might of the army but on the will of the people who had endorsed his rule. He once wrote that the best government was one in which the leader ruled "according to the will of all."

27

He seems to have sensed that the discontent among the artists might spread, like dissent over his Mexican adventure, into a wider critique of his regime. In any case, artists protesting that their right to exhibit had been infringed must have borne, in Louis-Napoléon's ears, uncomfortable parallels to opposition complaints about the government's wider violations of personal liberties.

The Emperor viewed the works with his riding crop in hand, occasionally halting the proceedings to express his astonishment at the jury's severity.

28

Not the least of his amazements was the sight of one of his own commissions among the rejected works, paintings of the

Four Seasons

done for the Salon de l'lmperatrice in the Élysée Palace. The artist for this commission was Paul-Cesar Gariot, a fifty-two-year-old painter who had been awarded a medal at the 1843 Salon. The Emperor may have viewed the rejection of these four paintings as a comment on his own artistic taste. Nor would he have been amused to see among the

refusés

a portrait of his wife painted by a female artist named Hortense Bourgeois.