The Judgment of Paris (15 page)

Raised among fervent royalists and Catholics as the stepson of a Norman aristocrat, Chennevières was a political conservative who despised both democracy and the common man. "Democracy has always horrified me," he once wrote, "and I see in it only principles that are corrosive and destructive for every society."

4

Seventy years after the French Revolution, he harked back nostalgically to the institutions of the ancien regime, claiming that the aristocracy, "in which the sound and strong head directs and contains the tail, is worth more than democracy, where the insolent and churlish tail drags along the weak and diminished head."

5

Chennevières's fellow Norman, Gustave Flaubert, a friend of Nieuwerkerke, had coined the word

democrasserie (crasse

meaning both "filth" and "dirty trick") to describe the way in which democracy led, in his opinion, to a lowering of artistic standards. Chennevières likewise detested the effects of democracy on the arts, where the tail, in his opinion, was threatening to wag the dog. He had little use for most modern art, dismissing the work of Courbet and other Realists as "democratic painting" and maintaining that Honoré Daumier (a friend of Meissonier from their student days on the îie Saint-Louis) should have his paints and brushes confiscated.

6

He was nostalgic for the time when the Salon had been an exclusive preserve where members of the Académie Royale de la Peinture et de la Sculpture, founded by Louis XIV in 1648, showed examples of their recent work. But after the French Revolution, the Académie Royale had been abolished and the Salon thrown open to all artists who could impress the jury. And while Manet and others found the juries too draconian in preventing the exposure of their work, Chennevières, like many conservatives, bemoaned what he regarded as the aesthetic free-for-all and galloping commercialization of the Salon.

Indeed, by the middle of the nineteenth century the Salon had become, in the eyes of many of its critics, little more than a marketplace for which commodities—such as easel paintings for the walls of middle-class apartments—were manufactured by the thousand. Chennevières's reservations about this commercialization were expressed by Ingres, another arch-conservative, who fulminated against this "bazaar" in which business ruled instead of art: "Artists are driven to exhibit there," he wrote, "by the attractions of profit, the desire to get themselves noticed at any price, by the supposed good fortune of an eccentric subject capable of producing an effect and leading to an advantageous sale."

7

In this view, little difference existed between the paintings shown at the Palais des Champs-Élysées and the expositions of cheeses or pigs that followed them. Both were commodities produced for no other purpose than a profitable commercial transaction. And the visitors to this bazaar were to be treated, in 1863, to a strange new variety of art.

The 1863 Salon opened, with even more than the usual excitement and anticipation, on the first of May, a Friday. The Palais des Champs-Élysées grew as crowded as ever as thousands of visitors poured through the enormous, flag-stoned entrance hall and made their way up the monumental staircases to the rooms on the first floor. Negotiating one's way through a 250-yard-long exhibition hall in which more than two thousand works of art were on display in a maze of rooms and indoor courtyards and gardens was a daunting task, but Chennevières and his helpers had tried to guide visitors through the labyrinth. The enormous exhibition hall had been partitioned, as usual, into several dozen rooms, each of which featured a letter of the alphabet above its door. Paintings by artists whose surnames began with A were hung in the first room, those with B in the next room, and so forth, allowing Salon-goers to make their way unerringly from A through Z.

Once inside each room, however, visitors were confronted by a disorderly confusion of paintings stacked on all four walls from floor to ceiling; some rooms were home to as many as two hundred canvases. These works were hung together in a promiscuous jumbling of styles and genres that witnessed, for example, portraits of pious Christian martyrs occupying space beside lubricious depictions of red-blooded satyrs or the undraped habitués of Turkish baths. Huge canvases were suspended next to tiny portraits, with almost every inch of wall space occupied. Viewing conditions were far from ideal. Paintings that had been "skyed"—that is, hung high on the wall—could not be appreciated without either sore necks or telescopic aids to vision, while the space in front of works by the most famous artists always grew dense with spectators jostling one another for a better view. "They come as they would to a pantomime or a circus," the philosopher Hippolyte Taine complained of these hordes.

8

In order to find their way through this maze—and also to help themselves form opinions on what they had seen—visitors could purchase the numerous guides, known as

salons,

that were written for newspapers of every description by the hundred art critics who stalked Paris.

9

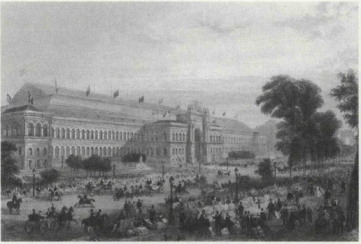

The Palais des Champs-Élysées

The Salon of 1863 had any number of eye-catching works on show. One of the most popular paintings—and what would become one of the most celebrated paintings of the nineteenth century—was

The Prisoner

by Jean-Léon Gérôme. A perennial favorite with the public if not always with the critics, Gérôme was, at the age of thirty-nine, one of France's most successful painters. He specialized in exceptionally detailed, delicately erotic scenes from ancient Greece and Rome as well as from modern-day Egypt and the Holy Land, through which he had traveled on several occasions. His patrons occupied the very highest levels of French society. His

Greek Interior,

a brothel scene shown at the Salon of 1850, had been bought by the Emperor's cousin, Prince Napoléon-Jerome, who then hired him to add to the decor of his spectacularly tasteless Paris mansion, the Villa Diomède. No sooner were these murals finished than the painter of belly dancers and snake charmers received a commission from Pope Pius IX to decorate the interior of His Holiness's private railway carriage.

The Prisoner

added further to Gérôme's reputation. An Oriental scene, it depicted a handcuffed prisoner in white robes lying crosswise in a boat rowed along the Nile at sundown as one of the turbaned captors taunted him with a song. Oozing with the placid exoticism and technical virtuosity that was Gérôme's trademark, it had caught the eye of an American collector named Edward Matthews, who tried unsuccessfully to buy it for 30,000 francs. A smallish painting only eighteen inches high by thirty-two inches wide, it received the sort of elbow-jogging, neck-craning attention usually accorded the works of Meissonier, with Gérôme boasting that it was "admired by both connoisseurs and idiots."

10

No Salon was complete without its share of controversial canvases, works that appalled the critics, scandalized the public and, of course, sucked enormous crowds into the Palais des Champs-Élysées. The Salon of 1863 did not fail to deliver. On show in Room M, for example—the room from which both Manet and Meissonier were so conspicuously absent—was Jean-François Millet's

Man with a Hoe.

This work depicted exactly what its title described: a peasant leaning wearily on his hoe before his furrow in the middle of a rocky field. The canvas was typical of Millet, a forty-nine-year-old painter of rustic scenes of toiling peasants. With its celebration of the worker,

Man with a Hoe

was precisely the sort of work that Nieuwerkerke and Chennevières denounced as "democratic painting." Many Salon critics found the painting repellent on aesthetic grounds, mocking the farm worker's ugliness and nicknaming him "Dumolard," a reference to Martin Dumolard, a grotesque-looking peasant from the village of Montluel, near Lyon, who had been beheaded a year earlier after a court found him guilty of the brutal murders of as many as twenty-five women.

Far more controversial even than Millet's homely peasant was the beautiful woman on show in Room C. The Salons positively teemed with painted female flesh at a time, ironically, when actual female flesh was a forbidden sight in Paris. Women were not permitted on the top floor of omnibuses in case they exposed an ankle or calf as they climbed or descended the steps; and the sexes were strictly prohibited from mingling—thanks to barriers, signposts and uniformed inspectors—at the various bathing spots along the Seine. Women were expected to cover themselves in shifts as they entered the water; even men were liable to arrest if they bathed without tops. The Salon, however, lifted a curtain to expose a fantasyland where, uninhibited by these stringent regulations, men and women frolicked together in stark-naked abandon. Mythological scenes graced by exquisite female nudes were therefore mainstays of the Salon, and never more so than in 1863. So many depictions of Venus (always a popular subject for a nude) appeared on the walls of the Palais des Champs-Élysées in 1863 that Théophile Gautier dubbed it the "Salon des Venus."

11

The clear winner among these goddesses, in terms of its crowd-pulling prowess, was Alexandre Cabanel's

The Birth of Venus

(plate 4A). The red-bearded Cabanel, who favored velvet jackets and flowing cravats, was one of the brightest stars in the artistic empyrean. A native of Montpellier, he had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts under François Picot and carried away the Prix de Rome in 1845. After his studies in Italy he returned to Paris to paint a number of prestigious commissions, including work in the Hôtel-de-Ville. A Salon favorite since 1843, when he showed his first work at the tender age of twenty, he had thrilled the crowds two years earlier with

Nymph Abducted by a Faun,

a risque mythological fantasy featuring a milk-white female nude swooning in the hairy grasp of a leering faun.

The Birth of Venus

dropped another depth charge of refined concupiscence into the Palais des Champs-Élysées. Supposedly showing Venus stirring to life on the waves, Cabanel's canvas presented its viewers with the arresting spectacle of a young nude with opulent contours and come-hither eyes lolling deliriously on her back. Paul Mantz, the critic for the

Gazettes des Beaux-Arts,

found her "wanton and lascivious" but declared she was, for all that, "harmonious and pure."

12

Yet not everyone agreed that Cabanel's Venus was altogether untainted by belowstairs passion. Mythological trappings and allusive names provided a flimsy pretext for acre upon acre of painted female flesh. But no amount of mythologizing—no hastily painted togas or garlands of laurel leaves—could save a painter if his work was thought to dwell on the brute senses rather than trying to capture the abstract ideals of beauty or virtue. For instance, Flaubert's friend Maxime du Camp believed a painted nude should exude no more carnality than a mathematical equation. "The naked body is an abstract being," he confidently declared.

13

And the flawless curves and powder-puff complexion of Cabanel's Venus could violate this proposition as easily as the lumpy flesh of one of Courbet's bathers.

14

As it transpired, du Camp, like many other critics, was aghast at Cabanel's

The Birth of Venus.

He was no prude, having darkened the doors of brothels from Paris to Cairo.

15

But when he looked at the painting du Camp saw not a philosophical meditation on beauty or truth but, rather, a sensual young woman "revealing herself" in a most immodest fashion—someone whose true milieu was not the mists of antiquity but the gaslights of modern Paris. She was such a creature, he claimed with a hypocritical and insincere horror, as one might encounter "at a ball, at that moment of intoxication that music, perfume and dancing create."

16

Many other critics were equally convinced of Cabanel's immoral designs. Arthur Stevens, a Belgian art dealer, found the work little more than pornographic fodder for dirty old men and adolescents, while Millet, smarting from criticism of his own work, would denounce Cabanel's "indecent" painting as a "frank and direct appeal to the passions of bankers and stockbrokers."

17

The republican art critic Théophile Thoré predicted an even more disreputable market for the work: it would be turned into colored lithographs, he claimed, to decorate the boudoirs of low-class prostitutes in the Rue Bréda.

18

These critics were therefore divided over whether Cabanel's Venus was really a high-class courtesan or a low-rent prostitute, but all agreed that the painting addressed itself to the base physical senses rather than the nobler passions of the soul—and none believed that the mythological allusion in the title in any way excused this transgression.