The Judgment of Paris (6 page)

Visions of the past may have abounded in France, but so too did unmistakable signs of the present, of a world that over the past few decades had been dramatically transformed through technology and invention. "Everything advances, expands and increases around us," wrote the photographer and traveler Maxime du Camp in 1858. "Science produces marvels, industry accomplishes miracles."

29

By the early 1860s, France was crisscrossed by 6,000 miles of railway track and 55,000 miles of telegraph wire. Over the previous ten years, eighty-five miles of wide new streets—made out of macadam and asphalt instead of cobblestones—had been laid in Paris under the guidance of Baron Georges Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine. In 1863 a three-wheeled wagon powered by an internal combustion engine, the invention of an engineer named Lenoir, rode these boulevards on a fifteen-mile return journey to Joinville-le-Pont. Those witnessing this triumphant progression must truly have believed themselves to be living in what a German critic, writing of Paris, would later call the "capital of the nineteenth century."

30

While Ernest Meissonier shunned this audacious new world by retreating into an eighteenth-century idyll of periwigs and cavaliers, not everyone remained convinced of the suitability of such a response. Du Camp, for one, found absurd the fact that, in an age of electricity and steam, artists were still producing mythological scenes featuring Venus and Bacchus. In a similar spirit, Baudelaire had written a treatise entitled

The Painter of Modern Life

in which he encouraged artists to abandon "the dress of the past" and take their subjects from modern life instead. He called on painters to embrace what he christened

la modernite,

by which he meant the fleeting and seemingly trivial world of contemporary life. Like Couture, he believed the task of an artist was not to regurgitate the forms of past centuries but to produce visions of this modern world—crowds, street scenes, vignettes of middle-class life—in all their splendor and all their ugliness.

31

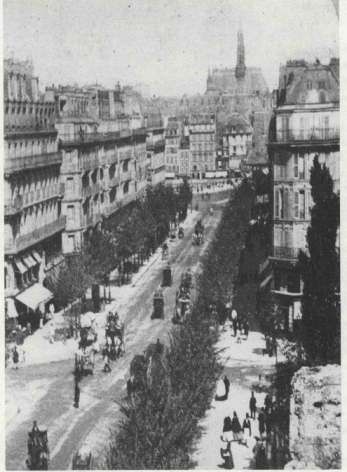

The Boulevard Saint-Michel, designed by Baron Haussmann

With his devotion to the art of previous centuries, Édouard Manet may have seemed an unlikely convert to this cause. The inspiration for his early paintings came mostly from Old Masters he had sketched in the Louvre and the Uffizi rather than from the everyday life he saw along the boulevards of Paris or in the cafés of Asnières.

Fishing at Saint-Ouen,

begun about 1860, was set on the banks of the Seine a mile or so downstream from Asnières, in the industrial suburb of Saint-Ouen; modeled on a work by Peter Paul Rubens, however, it showed not modern-day factory workers or boisterous holidaymakers but a couple in seventeenth-century dress posing beside the river. Still, Manet had begun paying heed to the advice of Baudelaire and Couture with canvases such as

The Absinthe Drinker

and

The Old Musician.

The latter canvas, painted in 1862, portrayed a number of indigents from the Batignolles, including a violinist from a gypsy colony—though even in this work Manet had borrowed some of his poses directly from paintings in the Louvre.

Determined to capture another scene from modern life, Manet began a canvas called

Le Bain,

or "The Bath," soon after his return from Asnières. A nude scene of modern-day Parisians,

Le Bain

would be, in its own way, as striking a vision of modernity as Haussmann's boulevards or Lenoir's gasoline-powered engine.

I

F SOMETHING WAS worth doing, Ernest Meissonier always maintained, it was worth doing properly. He had been conscientious even as a child, showing remarkable patience in tasks like blacking his boots or, when put to work in the druggist's shop, tying up parcels of medicine for customers.

1

He applied the same exacting standards to his paintings, each of which took months, if not years, of concentrated effort. "Although I work under great pressure from all sides," he claimed, "I am always altering. I am never satisfied."

2

Because he often spent one day scraping away the paint he had spent the previous day laboriously applying, he referred to his works-in-progress as "Penelope's webs," an allusion to how each night Odysseus's wife Penelope would unravel the shroud she was weaving on her loom for Laertes, her father-in-law. Sometimes Meissonier did not even bother to scrape away the offending part of the work; he simply repainted the entire canvas, often so many times that the finished product was merely the uppermost layer of a series of palimpsests. "Perfection," he claimed, "lures one on."

3

Meissonier always spent many months researching his subject, finding out, for example, the precise sort of coats or breeches worn at the court of Louis XV, then hunting for them in rag fairs and market stalls or, failing that, having them specially sewn by tailors. Historical authenticity was taken very seriously in the nineteenth century, not just by Meissonier but also by other artists who likewise went to great lengths to ensure the authenticity of their works. When Théodore Géricault began his masterpiece,

The Raft of the "Medusa"

—a huge canvas depicting survivors of a notorious shipwreck—he had shown exceptional diligence. Starting work in 1818, two years after the event, he pored over published accounts of the ill-fated voyage, interviewed a number of survivors, employed some of them as models, and studied corpses in a hospital morgue. He even hired the carpenter of the

Medusa

to build him an exact replica of the raft. The resulting canvas was shockingly grisly and violent—but accurate in its every gory detail.

*

This kind of historical reconstruction had always been Meissonier's stock-in-trade. Recently he had spent more than three years on a painting that was a mere thirty inches wide by seventeen inches high:

The Emperor Napoléon III at the Battle of Solferino

(plate 2A). The work, a battle scene, had been something of a departure for the painter of

bonshommes

and musketeers. Marking the new direction in Meissonier's career, it took as its subject a victorious battle fought by the French against the Austrians in 1859, when the emperor Napoléon III, together with Victor Emmanuel II, King of Piedmont and Sardinia, tried to oust the Habsburgs from their territories in northern Italy. When hostilities commenced early in the summer of 1859, Meissonier had received a commission from the government to illustrate several scenes from the campaign. He set off for the front in Lombardy, taking with him a servant, two horses and a supply of pencils and paints. Arriving in time to witness a bloody battle fought outside the village of Solferino, he made numerous on-the-spot sketches of the action, barely escaping with his life after several bullets whizzed past his head when he accidentally strayed into the thick of the action in his quest for a good vantage point.

Meissonier's studies for

The Battle of Solferino

had continued long after the war ended. At the army camp in Vincennes, east of Paris, he painted further sketches of soldiers, and at the Château de Fontainebleau he did portrait studies of both Napoléon III—who was going to be the focus of the scene—and his horse, Buckingham. He even made a return trip to Solferino, a year after the battle, to make still more studies of the bleak, dusty landscape. The painting was accepted by the judges, sight unseen, for the Salon of 1861, where Meissonier had been hoping to show the critics that he had risen above his lucrative "musketeer style" to paint something more ambitious in conception. It failed to materialize: the master was still perfecting the work in his studio. Nor did it appear the following year, as announced, at the Universal Exposition in London. Meissonier would not complete the painting until January of 1863, almost four years after his first expedition to Solferino.

The Campaign of France,

commissioned while

The Battle of Solferino

was still on his easel, required equally prolonged and unstinting researches. Starting work in 1860, he consulted Adolphe Thiers, both in person and in print. He interviewed survivors of the 1814 campaign, such as the Due de Mortemart, one of Napoléon's generals. He also consulted Napoléon's valet, an old man named Hubert. He made a special journey to Chantilly to see Napoléon's groom, Pillardeau, whose home was a bizarre shrine dedicated to the memory of Napoléon and the Grande Armée, complete with

papier-mache

replicas of the kind of bread eaten by the soldiers. Meissonier thereby became an expert on every aspect of Napoléon's life, from how he changed his breeches every day because he soiled them with snuff, to how he undressed himself—for reasons of modesty—only in total darkness.

4

Meissonier did not begin the actual painting of any of his works until he had first made numerous preparatory sketches and studies. And he did not begin these until he had worked out the composition of the painting in the most elaborate detail, usually by means of a three-dimensional scale model of the scene. A number of painters had resorted to this strategy, from Michelangelo, who made wax figurines of many of the characters he painted, to the eighteenth-century English landscapist Thomas Gainsborough, who fashioned tabletop models with sand, moss, twigs, bits of mirror for water or sky, and miniature horses and cows. But Meissonier, as ever, took matters a step or two farther. Thus, for

The Campaign of France

he sculpted in wax a series of highly detailed models, some six to eight inches high, of Napoléon and his generals, as well as the horses on which they sat. These models he then arranged in his studio on a wooden platform four feet square. He also made models of tumbrils and wagons, which he proceeded to drag across a muddy landscape—carefully molded from clay spread on top of the platform—to create the furrowed road along which Napoléon trekked with his generals. He prided himself on these creations, considering himself, according to a friend, "by turns tailor, saddler, joiner, cabinetmaker."

5

Absolutely nothing was left to chance or imagination; everything had to be rigorously and impeccably correct. Meissonier had faced a problem, though, with his

tableau vivant

for

The Campaign of France.

Despite the presence of Napoléon and his generals, this new painting was conceived as, first and foremost, a snowscape: a panorama in which the Grande Armée plods across a vast expanse of snow beneath a leaden sky.

6

And since Meissonier would not paint anything without first having the correct specimen before his eyes, he had naturally found himself in need of snow. So across the expanse of furrowed clay he had sprinkled handfuls of finely granulated sugar and, to give his snow its glitter, pinches of salt. With a shod hoof, likewise executed in miniature, he then meticulously pressed the imprints of the horses' feet. The leadership of the Grande Armée was thereby devised in perfect effigy against a snowy landscape.

"What an effect of snow I obtained!" Meissonier had proudly declared when the model was finished.

7

Unfortunately, the sugar soon attracted the attention of bees from a neighbor's hive, forcing him to replace it with flour—which merely served to bring on another invasion of unwanted guests: "The mice came and ravaged my battlefield," he lamented.

8

At which point Meissonier decided to stage

The Campaign of France

on a larger scale, in the grounds of his house at Poissy.

Work on this full-scale mock-up had begun around the summer of 1861, with elaborate plans and preparations more typical of staging an opera than painting a picture. Models were hired, costumes sewn, and a white horse, a double for Napoléon's charger, brought to Poissy from the stables of Napoléon III. Then, to simulate snow, vast quantities of flour were raked across the grounds of the Grande Maison—so much that at the end of each day Meissonier's models and their horses needed to be de-whitened by a team of servants.

9

Meanwhile the escort of generals posed on horseback. The model serving for Marshal Ney—riding immediately behind Napoléon—wore his coat draped over his shoulders like a cape, a sartorial detail Meissonier had picked up from a chance encounter in a train carriage with a medic who had served under Marshal Ney at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813. The coat itself was authentic, since Meissonier had borrowed it, along with the rest of the uniform, from Marshal Ney's son.

10

The model serving for Napoléon was, of course, Meissonier himself.

11