The Judgment of Paris (4 page)

Meissonier hoped to capture precisely this aspect of Napoléon's character: his admirable courage in the face of staggering adversity. "All have lost faith in him," Meissonier wrote of the episode. "Doubt has come. He alone believes that all is not yet lost."

39

The Campaign of France

would depict the Emperor, the great and tragic genius celebrated by Thiers for the originality and grandeur of his "astonishing deeds."

40

Meissonier showed him astride his white charger and at the head of the exhausted Grande Armée, grimly leading his weary soldiers through snowy wastes to engage their formidable enemy in a last, desperate struggle. Grand in manner and noble in subject, it would be exactly the sort of work he had dreamed of painting as a young man in Cogniet's studio.

The Grande Maison

A

S MEISSONIER WORKED on

The Campaign of France,

a short distance away in Paris, in a small studio in the Batignolles district, another artist was preparing a painting of a quite different sort. Édouard Manet, at thirty-one, was seventeen years younger than Meissonier. He lived in a three-room apartment in the Rue de l'Hôtel-de-Ville and did his painting in his studio nearby in the Rue Guyot. "Bohemian life," wrote Henri Murger, "is possible nowhere but in Paris,"

1

and nowhere in Paris was bohemian life more possible—in the early 1860s at least—than in the Batignolles. A mile north of the Seine, this lively working-class neighborhood had low rents, open-air cafés, immigrants from Poland and Germany, and an itinerant population of ragpickers, gypsies, artists and writers. By no means was it Paris's cleanest or most peaceful enclave. At its heart was France's busiest railway station. Each year millions of passengers poured through the Gare Saint-Lazare on excursions to Rouen, Le Havre or more local destinations such as Asnières or Argenteuil. From the railway tracks, which ran north into the industrial suburb of Clichy, came the stink of burning coal, showers of sparks and cinders, and constant whistle blasts that a friend of Manet once described as sounding like the "piercing shrieks of women being violated."

2

The dandyish Manet looked more than a little incongruous in the bustle and smoke of the Batignolles. His usual costume consisted of a top hat, frock coat, gloves of yellow suede, a walking stick and, according to a friend, "intentionally gaudy trousers."

3

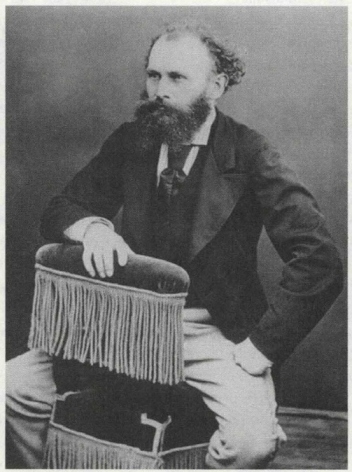

If Meissonier was pugnacious and arrogant, Manet, a handsome young man with reddish-blond hair, was the personification of charm. Witty and sociable, he possessed both an infectious humor and a bold streak of independence that made him a natural leader among younger artists. One of them, an Italian named Giuseppe De Nittis, claimed to love him for his "sunny soul," adding: "No one has ever been kinder, more courageous, or more dependable."

4

Another friend, the poet Théodore de Banville, even paid homage in verse to Manet's numerous allurements:

The laughing, blond Manet,

Emanating grace, Gay, subtle and charming,

With the beard of an Apollo,

Had from head to toe

The appearance of a gentleman.

5

The "laughing, blond Manet" was indeed every inch a gentleman. He had been born and raised in more prestigious surroundings than the Batignolles, at

Édouard Manet (Nadar)

his parents' home on the Left Bank of the Seine, in the aristocratic Faubourg Saint-Germain. The house stood across the street from the government's official art school, the École des Beaux-Arts, and across the river from the Louvre, the former royal palace that had served since 1793 as a national art museum. As a boy, Manet had been taken on regular visits to the Louvre by his maternal uncle, Colonel Edmond Fournier, a military man with an artistic bent. Fittingly for someone raised in such an environment, he had decided at a young age that he would become a painter. His father had other ideas. Auguste Manet was the son of the former mayor of Gennevilliers, a small town on the Seine where a street had been christened with the family name. Auguste, a lawyer, had served as the principal private secretary to the Minister of Justice and, after 1841, as a magistrate. He drew a comfortable salary of 20,000 francs per year presiding over cases involving paternity suits, contested wills and violations of copyright. His wife, Édouard's mother, came with an even more impressive pedigree. The daughter of a diplomat, she was the goddaughter of one of Napoléon's generals, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, who later fought against the Emperor in the 1814 campaign and four years later became King Karl XIV of Sweden.

Édouard Manet (Nadar)

Young men with such commendable forebears did not become painters, or so Auguste Manet believed. Instead, he had in mind for his eldest son a career in law. Alas, young Édouard had failed to distinguish himself at school, except in gymnastics, in which he excelled, and penmanship, where he was judged particularly atrocious. He passed his baccalauréat, in the end, only because his father knew the school's director.

6

With careers in law and art both preempted, Édouard had set his sights on the French Navy. This plan too seemed doomed when he failed the entrance examination for the naval academy: "a waste of time," his examiner had gloomily observed after surveying the result of his test.

7

However, in 1847 a law was passed guaranteeing admission to the academy to anyone who spent eighteen months on board a naval vessel. Manet therefore went off to Brazil on board the

Havre and Guadeloupe,

which weighed anchor in December 1848; but by the time the vessel returned to France six months later the seventeen-year-old sailor possessed no further appetite for the high seas. Within the year, his father finally having relented, he began his training as an artist. He had no wish to enter the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where originality and individuality were discouraged, and where students learned anatomy and geometry but not, bizarrely, how to paint. Manet began his studies, instead, in the studio near the Place Pigalle of a young painter named Thomas Couture. Known for encouraging spontaneity and self-expression among his students, the thirty-four-year-old Couture nonetheless had an unimpeachable artistic pedigree: he was a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, a former winner of the Prix de Rome—the highest prize available to students at the École—and a member of the Legion of Honor. He had also executed the portrait of, among others, Frédéric Chopin. Auguste Manet must have regarded him as a respectable member of what was otherwise, in his opinion, a fairly disreputable profession.

Manet was treading a similar path to that of Ernest Meissonier, who had likewise shunned the École des Beaux-Arts in favor of studying in the workshop of a respected painter. But there the similarities ended. Meissonier had exposed his first painting at the Paris Salon, a juried exhibition, at the astonishingly youthful age of nineteen, claiming his first medal six years later. Édouard Manet, on the other hand, appeared to be far less precocious, clashing frequently with Couture, a notably generous and broad-minded teacher who nonetheless believed his pupil to be fit only for drawing caricatures. According to legend, Couture told Manet that he would never be anything more than the "Daumier of your time," a reference to Honoré Daumier, an artist known much better for his barbed political cartoons than for his paintings.

8

Manet nevertheless remained under Couture's tutelage for almost six years, during which time he spent many hours copying prints and paintings in the Louvre, including works by Diego Velázquez—a particular favorite—and Giulio Romano. He had been intoxicated by the art of previous centuries, and at various times he made visits to Venice, Florence, Rome, Amsterdam, Vienna and Prague, making sketches in their churches and museums. He took three trips to Italy, where he copied, among other masterpieces, Raphael's frescoes in the Vatican Apartments and, in the Uffizi in Florence, Titian's

Venus of Urbino.

9

Inspired by these journeys, he planned canvases showing biblical and mythological characters, such as Moses, Venus and a heroine from Greek legend, Danae—exactly the sort of works commended by the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Manet had befriended Charles Baudelaire, a poet who had become notorious with the publication in 1857 of

Les Fleurs du mal.

Together they frequented the Café Tortoni, which stood on the corner of the Boulevard des Italiens and the Rue Taitbout, a temptingly short stroll from Manet's studio in the Batignolles. Manet also took a mistress at this time, a blonde Dutchwoman named Suzanne Leenhoff. Two years his senior, Suzanne had given him piano lessons for a few months in 1851 before becoming pregnant and then giving birth, in January 1852, to a boy of mysterious paternity who was christened Léon-Édouard Koella.

10

Whether or not he was the father, by the late 1850s Manet was living with both Suzanne and her child, who masqueraded in public as her younger brother. Showing a touching domestic regard that belied his more bohemian pursuits, Manet took Léon for walks through the Batignolles each Thursday and Sunday.

Not until 1859, when he was twenty-seven years old, did Manet feel himself ready to launch his career at the Paris Salon, or "The Exhibition of Living Artists," as it was more properly called. This government-sponsored exhibition was known as the "Salon" since for many years after its inauguration in 1673 it had taken place in the Salon Carré, or Square Room, of the Louvre. By 1855 it had moved to the more capacious but less regal surroundings of the Palais des Champs-Élysées, a cast-iron exhibition hall (formerly known as the Palais de l'Industrie) whose floral arrangements and indoor lake and waterfall could not disguise the fact that, when not hosting the Salon, it accommodated equestrian competitions and agricultural trade fairs.

The Salon was a rare venue for artists to expose their wares to the public and—like Meissonier, its biggest star—to make their reputations. One of the greatest spectacles in Europe, it was an even more popular attraction, in terms of the crowds it drew, than public executions. Opening to the public in the first week of May and running for some six weeks, it featured thousands of works of art specially—and sometimes controversially—chosen by a Selection Committee. Admission on most afternoons was only a franc, which placed it within easy reach of virtually every Parisian, considering the wage of the lowest-paid workers, such as milliners and washerwomen, averaged three to four francs a day. Those unwilling or unable to pay could visit on Sundays, when admission was free and the Palais des Champs-Élysées thronged with as many as 50,000 visitors—five times the number that had gathered in 1857 to watch the blade of the guillotine descend on the neck of a priest named Verger who had murdered the Archbishop of Paris. In some years, as many as a million people visited the Salon during its six-week run, meaning crowds averaged more than 23,000 people a day.

*