The Judgment of Paris (2 page)

4A. (Alexandre Cabanel)

The Birth of Venus

5A. (Claude Monet)

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

5B. originally entitled (Édouard Manet)

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe,

Le Bain

6A. (Édouard Manet)

The Races at Longchamp

6B. (Ernest Meissonier)

Friedland

7A. (Ernest Meissonier)

The Siege of Paris

7B. (Édouard Manet)

The Railway

8A. (Édouard Manet)

Le Bon Bock

8B. (Claude Monet)

Bathers at La Grenouillère

O

NE GLOOMY JANUARY day in 1863, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, the world's wealthiest and most celebrated painter, dressed himself in the costume of Napoléon Bonaparte and, despite the snowfall, climbed onto the rooftop balcony of his mansion in Poissy.

A town with a population of a little more than 3,000, Poissy lay eleven miles northwest of Paris, on the south bank of an oxbow in the River Seine and on the railway line running from the Gare Saint-Lazare to the Normandy coast.

1

It boasted a twelfth-century church, an equally ancient bridge, and a weekly cattle market that supplied the butcher shops of Paris and, every Tuesday, left the medieval streets steaming with manure. There was little else in Poissy except for the ancient priory of Saint-Louis, a walled convent that had once been home to an order of Dominican nuns. The nuns had been evicted during the French Revolution and the convent's buildings either demolished or sold to private buyers. But inside the enclosure remained an enormous, spired church almost a hundred yards in length and, close by, a grandiose house with clusters of balconies, dormer windows and pink-bricked chimneys: a building sometimes known as the Grande Maison.

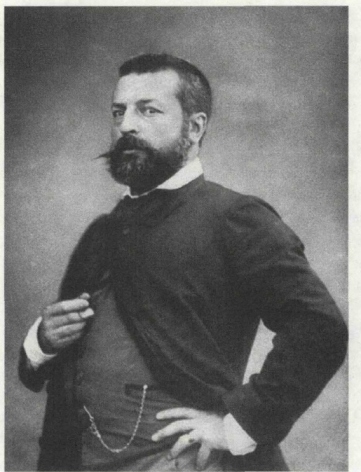

Ernest Meissonier

*

had occupied the Grande Maison for most of the previous two decades. In his forty-eighth year he was short, arrogant and densely bearded: "ugly, little and mean," one observer put it, "rather a scrap of a man."

2

A friend described him as looking like a professor of gymnastics,

3

and indeed the burly Meissonier was an eager and accomplished athlete, often rising before dawn to rampage through the countryside on horseback, swim in the Seine, or launch himself at an opponent, fencing sword in hand. Only after an hour or two of these exertions would he retire, sometimes still shod in his riding boots, to a studio in the Grande Maison where he spent ten or twelve hours each day crafting on his easel the wonders of precision and meticulousness that had made both his reputation and his fortune.

4

To overstate either Meissonier's reputation or his fortune would have been difficult in the year 1863. "At no period," a contemporary claimed, "can we point to a French painter to whom such high distinctions were awarded, whose works were so eagerly sought after, whose material interests were so guaranteed by the high prices offered for every production of his brush."

5

No artist in France could command Meissonier's extravagant prices or excite so much public attention. Each year at the Paris Salon—the annual art exhibition in the Palais des Champs-Élysées—the space before Meissonier's paintings grew so thick with spectators that a special policeman was needed to regulate the masses as they pressed forward to inspect his latest success.

6

Collected by wealthy connoisseurs such as James de Rothschild and the Due d'Aumale, these paintings proved such lucrative investments that Meissonier's signature was said to be worth that of the Bank of France.

7

"The prices of his works," noted one awestruck art critic, "have attained formidable proportions, never before known."

8

Meissonier's success in the auction rooms was accompanied by a chorus of critical praise and—even more unusual for an art world riven by savage rivalries and piffling jealousies—the respect and admiration of his peers. "He is the incontestable master of our epoch," declared Eugène Delacroix, who predicted to the poet Charles Baudelaire that "amongst all of us, surely it is he who is most certain to survive!"

9

Another of Meissonier's friends, the writer Alexandre Dumas

fils,

called him

"the

painter of France."

10

He was simply, as a newspaper breathlessly reported, "the most renowned artist of our time."

11

Ernest Meissonier

From his vantage point at the top of his mansion this most renowned artist could have seen all that his tremendous success had bought him. A stable housed his eight horses and a coach house his fleet of carriages, which included expensive landaus, berlines, and victorias. He even owned the fastest vehicle on the road, a mail coach. All were decorated, in one of his typically lordly gestures, with a crest that bore his most fitting motto:

Omnia labor,

or "Everything by work." A greenhouse, a saddlery, an English garden, a photographic workshop, a duck pond, lodgings for his coachman and groom, and a meadow planted with cherry trees—all were ranged across a patch of land sloping down to the embankments of the Seine, where his two yachts were moored. A dozen miles upstream, in the Rue des Pyramides, a fashionable street within steps of both the Jardin des Tuileries and the Louvre, he maintained his Paris apartment.

12

The Grande Maison itself stood between the convent's Gothic church and the remains of its ancient cloister. Meissonier had purchased the pink-bricked eighteenth-century orangery, which was sometimes known as Le Pavilion Rose, in 1846. In the ensuing years he had spent hundreds of thousands of francs on its expansion and refurbishment in order to create a splendid palace for himself and his family. A turret had been built above an adjoining cottage to house an enormous cistern that provided the Grande Maison with running water, which was pumped through the house and garden by means of a steam engine. The house also boasted a luxurious water closet and, to warm it in winter, a central heating system. A billiard room was available for Meissonier's rare moments away from his easel.

Yet despite these modern conveniences, the Grande Maison was really intended to be an exquisite antiquarian daydream. "My house and my temperament belong to another age," Meissonier once said.

13

He did not feel at home or at ease in the nineteenth century. He spoke unashamedly of the "good old days," by which he meant the eighteenth century and even earlier. He detested the sight of railway stations, cast-iron bridges, modern architecture and recent fashions such as frock coats and top hats. He did not like how people sat cross-legged and read newspapers and cheap pamphlets instead of leather-bound books. And so from the outside his house—all gables, pitched roofs and leaded windows—was a vision of eighteenth-century elegance and tranquillity, while on the inside the rooms were decorated in the style of Louis XV, with expensive tapestries, armoires, embroidered fauteuils, and carved wooden balustrades.

The Grande Maison included not one but, most unusually, two large studios in which Meissonier could paint his masterpieces. The

atelier d'hiver,

or "winter workshop," featuring bay windows and a large fireplace, was on the top floor of the house, while at ground level, overlooking the garden, he had built a glass-roofed annex known as the

atelier d'e'te,

or "summer workshop." Both abounded with the tools of his trade: canvases, brushes and easels, but also musical instruments, suits of armor, bridles and harnesses, plumed helmets, and an assortment of halberds, rapiers and muskets—enough weaponry, it was said, to equip a company of mercenaries. For Meissonier's paintings were, like his house, recherche figments of an antiquarian imagination. He specialized in scenes from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century life, portraying an evergrowing cast of silk-coated and lace-ruffed gentlemen—what he called his

bonshommes,

or "good fellows"—playing chess, smoking pipes, reading books, sitting before easels or double basses, or posing in the uniforms of musketeers or halberdiers. These musicians and bookworms striking their quiet and reflective poses in serene, softly lit interiors, all executed in microscopic detail, bore uncanny similarities to the work of Jan Vermeer, an artist whose rediscovery in the 1860s owed much to the ravenous taste for Meissonier—and one whose tremendous current popularity approaches the enthusiastic esteem in which Meissonier himself was held in mid-nineteenth-century France.

Typical of Meissonier's work was one of his most recent creations,

Halt at an Inn,

owned by the Due de Morny, a wealthy art collector and the illegitimate half brother of the French Emperor, Napoléon III. Completed in 1862, it featured three eighteenth-century cavaliers in tricorn hats being served drinks on horseback outside a half-timbered rural tavern: a charming vignette of the days of old, without a railway train or top hat in sight. Meissonier's most famous painting, though, was

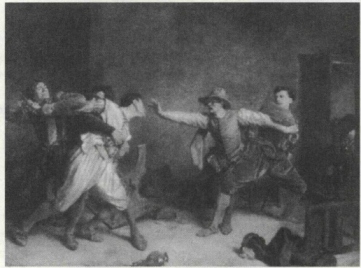

The Brawl,

a somewhat less decorous scene depicting a fight in a tavern between two men dressed—as usual—in opulent eighteenth-century attire. Awarded the Grand Medal of Honor at the Salon of 1855, it was owned by Queen Victoria, whose husband and consort, Prince Albert, had prized Meissonier above all other artists. At the height of the Crimean War, Napoléon III had purchased the work from Meissonier for 25,000 francs—eight times the annual salary of an average factory worker—and presented it as a gift to his ally across the Channel.

"If I had not been a painter," Meissonier once declared, "I should have liked to be a historian. I don't think any other subject could be so interesting as history."

14

He was not alone in his veneration of the past. The mid-nineteenth century was an age of rapid technological development that had witnessed the The Brawl

(Ernest Meissonier)

invention of photography, the electric motor and the steam-powered locomotive. Yet it was also an age fascinated by, and obsessed with, the past. The novelist Gustave Flaubert regarded this keen sense of history as a completely new phenomenon—as yet another of the century's many bold inventions. "The historical sense dates from only yesterday," he wrote to a friend in 1860, "and it is perhaps one of the nineteenth century's finest achievements."

15

Visions of the past were everywhere in France. Fashions at the court of Napoléon III aped those of previous centuries, with men wearing bicorn hats, knee breeches and silk stockings. The country's best-known architect, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, had spent his career busily returning old churches and cathedrals to their medieval splendor. By 1863 he was creating a fairy-tale castle for the emperor at Pierrefonds, a knights-in-armor reverie of portcullises, round towers and cobbled courtyards.

The Brawl

(Ernest Meissonier)

This sense of nostalgia predisposed the French public toward Meissonier's paintings, which were celebrated by the country's greatest art critic, Théophile Gautier, as "a complete resurrection of the life of bygone days."

16

Meissonier's wistful visions appealed to exactly the same population that had made

The Three Musketeers

by Alexandre Dumas

père,

first published in 1844, the most commercially successful book in nineteenth-century France.

17

Indeed, with their cavaliers decked out in ostrich plumes, doublets and wide-topped boots, many of Meissonier's paintings could easily have served as illustrations from the works of Dumas, a friend of the painter who, before his bankruptcy, had lived in equally splendid style in his "Château de Monte Cristo," a domed and turreted folly at Marly-le-Roi, a few miles upstream from Meissonier. Both men excelled at depicting scenes of chivalry and masculine adventure against a backdrop of pre-Revolutionary and pre-industrial France—the period before King Louis XVI was marched to the steps of the guillotine and the old social relations were destroyed, in the decades that followed, by new economic forces of finance and industry.

18

"The age of chivalry is gone," wrote Edmund Burke, a fierce critic of the French Revolution who lamented the loss, after 1789, of "manly sentiment and heroic enterprise."

19

But the age of chivalry had not entirely vanished in France: by the middle of the nineteenth century it lingered eloquently in Dumas's novels, in Viollet-le-Duc's spires and towers, and in Meissonier's jewel-like "musketeer" paintings.