The Judgment of Paris (18 page)

All told, in the annals of French art criticism, Manet had actually escaped rather lightly. Vicious reviews were all too frequent in nineteenth-century France; no one was immune from the venomous quills of the critics. Ingres, for example, had been the recipient of dozens of poisonous reviews throughout his career. His

Grande Odalisque,

exhibited at the Salon of 1819, attracted such hateful notices (the critics had seized on the fact that the reclining woman had three vertebrae too many) that he was moved to lament how his work had become "so much prey for ravenous dogs."

36

Fifteen years later, at the Salon of 1834, his

Martyrdom of Saint-Symphorian

was assailed so fiercely that he shut his studio, left Paris for the next seven years, and for more than two decades refused to exhibit at the Salon. His long-awaited return, in 1855, was promptly met with a review of unbridled malevolence: "Before this antiquated and non-majestic painting," a critic for

Le Figaro

informed his readers, "my nostrils are invaded by whiffs of warm, sour and nauseating air . . . I'm sorry to say this to delicate readers, but it's like the taste of a sick man's handkerchief."

37

Delacroix fared no better. His

Massacre of Chios

had been treated to unanimously hostile reviews at the Salon of 1824, where it was mocked as "the massacre of painting."

38

Worst of all, though, was the fate of Baron Gros, a talented student of Jacques-Louis David.

Hercules and Diomèdes

received such merciless reviews at the 1835 Salon that Gros drowned himself in a tributary of the Seine.

Manet was not the only

refuse

spared, for the most part, the wrath of the critics, many of whom sheathed their daggers as they surveyed the rest of the exhibition, which was not the critical catastrophe for which the members of the Selection Committee had been hoping. Though far from impressed by the exhibition, Charles Brun claimed that at least the paintings were not as dreadful a sight as the sneering crowds standing in front of them.

39

Chesneau even questioned the extent of this mockery, pointing out that while the majority of those who came to the Salon des Refusés found all of the paintings equally bad, some visitors, at least, shook their heads and questioned the harshness of the jury.

40

Other writers took the jury itself sternly to task. In

Le Figaro,

a critic calling himself Monsieur de Cupidon wrote that if one entered the Salon des Refusés with a smile, one departed feeling "serious, anxious and disturbed" at the injustices perpetrated against the Refusés, who, he noticed, "bore their name proudly."

41

The journalist and art critic Théodore Pelloquet likewise bearded the jury. He wrote in his biweekly review that the Salon des Refusés included some fifty paintings that were superior to the standard of the canvases accepted by the Selection Committee for the official Salon. "If we add to this figure those paintings which their authors withdrew," he further noted, "the Institut's inadequacy at continuing in its present role is beyond debate."

42

Pelloquet raised a question that had been on the lips of many people even before the Salon des Refusés opened its doors: given their controversial performance, should the members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts continue to staff the Selection Committee? Was this team of eminent painters really to be trusted with their hands on the rudder of French art?

From the works on show in the Salon des Refusés, educated observers, not least the artists themselves, could see that the jury was systematically barring from the Salon a particular style of painting in favor of the sort of art practiced by many of its own members and taught at the École des Beaux-Arts. The difference was one of both subject matter and technique. Many of the

refusés

had favored landscapes, while the jury instinctively sanctioned historical or mythological works from which moral lessons could be extracted. And whereas the jury preferred the smooth finish seen in the works of Gérôme and Cabanel, where all marks of the brush were deftly effaced, the canvases of many of the

refuse's,

Manet's included, featured a skimpiness of detail that aimed for an overall aesthetic impact—what Corot called the "first impression"—rather than an exactingly precise depiction of minutiae.

One of the most perceptive art critics, Théophile Thoré, summed up the aims of many of these rejected painters: "Instead of seeking what the connoisseurs of classic art call 'finish,' they aspire to create an effect through a striking harmony, without concern for either correct lines or meticulous detail."

43

This battle—between "finishers" and "sketchers"—was ultimately one, Thoré claimed, between "conservatives and innovators, tradition and originality."

44

If the conservatives held the bastion of the Institut de France, the innovators were grouping together and organizing themselves outside its walls, whether in Jean Desbrosses's studio or the Café de Bade. Those who pushed through the turnstiles of the Palais des Champs-Élysées amid peals of laughter may have little suspected it at the time, but they had seen, Thoré and many others believed, the future of painting.

E

RNEST MEISSONIER HAD a passion, amounting almost to a mania, for sketching and drawing. His rare moments away from his easel were spent doodling on scraps of paper. As a young man he scribbled pencil drawings as he sat biding his time in the anterooms of book publishers; and after his election to the Institut de France he sketched his colleagues as they sat snoozing beside him at meetings. His mania was so pronounced that his handiwork sometimes spilled over from his paper onto anything within reach of his pencil or brush. His friend Philippe Burty, a frequent guest at the Grande Maison, observed how Meissonier "sometimes amused himself by tracing large, rather audacious drawings on the walls of the stairway and corridors leading to his studio."

1

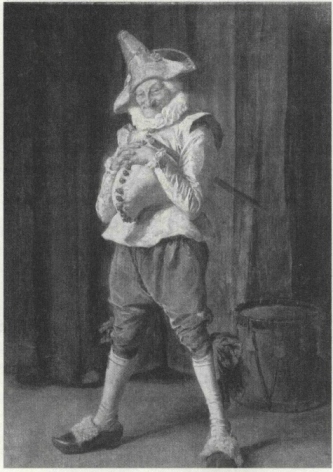

Two of these capricious sketches were comical versions of Polichinelle, the anarchic figure from the Italian commedia dell'arte that he had also created—while in the grip of a similar spasm of doodling—on the door of a friend, the courtesan Madame Sabatier.

Meissonier's idle sketches were not limited to doors or stairwells. Another friend, Charles Yriartre, art critic for

Le Figaro,

passing through Poissy on his way to pay his respects at the Grande Maison, was once surprised by the sight of a life-size Napoleonic soldier sketched in charcoal on a newly whitewashed wall beside the Seine. "The perfect anatomical accuracy and boldness of the execution, the style of the costume as well as something indescribable," concluded Yriarte, "revealed the master as a great decorator."

2

Even Meissonier's graffiti were masterpieces of detail and execution.

Yriarte attributed this curious obsession to Meissonier's restless inability to put down his pencil or brush and stop working. Another friend, the Russian painter Vassílí Verestchagín, claimed—stretching the facts only slightly—that Meissonier "never knew any rest or holiday" and "worked unceasingly all the 365 days of the year."

3

This dedication to his work inevitably meant that Meissonier led an increasingly retired life as he shut himself away in his studio in Poissy. His life at the Grande Maison was peaceable, disciplined and salubrious. An early riser, he would breakfast alone with a book at his elbow: heavyweight literature such as leather-bound editions of Shakespeare, Corneille, Moliere and Homer. Having finished eating, he would speak to the groom and, at six thirty, rouse his nineteen-year-old son Charles from his bed for a ride on horseback along the riverbank or into the Forest of Saint-Germain.

Polichinelle

(Ernest Meissonier

Meissonier was a great lover and tireless painter of horses: there was in a horse, he said, "enough to study all one's life."

4

Of the eight horses in his stable, his two favorites were a gray named Bachelier and a mare, Lady Coning-ham, which had been his mount at the Battle of Solferino. Also present for these early-morning excursions through the countryside were Meissonier's greyhounds, several of which had been given to him by his friend Alexandre Dumas

fils.

5

So devoted was Meissonier to these dogs that he included greyhounds on the coat of arms he painted onto the doors of his fleet of expensive carriages. These elegant vehicles were sometimes used by Meissonier to ferry his family on fifty-mile excursions through the countryside to Auvers-sur-Oise, a town north of Paris to which his friend Daubigny had recently moved.

Besides horses, greyhounds and fashionable carriages, Meissonier also had a passion for boats. A flotilla of skiffs, cutters and yachts was moored on his stretch of the riverfront; two of them, the

Charles

and the

Therese,

were named for his children. Dressed in a pilot coat and sou'wester, he often took them onto the river, with his children and their friends serving as his crewmates. The Seine at Poissy was more peaceful than at Asnières or Argenteuil, disturbed only by anglers in their skiffs or the occasional barge making its way upstream toward Paris. Meissonier would scud along the channels between the islands in the river, downstream past the Île-de-Villennes or upstream to where reflections of the twelfth-century bridge and a riverside inn, L'Esturgeon, shimmered in the water. The voyage finished, Meissonier would strike the sail and carry the rigging back to the house, looking, according to a friend, like an "Icelandic fisherman."

6

He then sometimes started painting in his studio while still wearing his pilot coat.

Following his disheartening experiences on the painting jury, Meissonier was more inclined than ever to forgo the bright lights of Paris in favor of his rural idyll in Poissy. The artistic controversies that culminated in the institution of the Salon des Refusés had marked a low point in his brilliant career. The failed campaign against Nieuwerkerke; the boycott of the Salon that prevented him from showcasing his new artistic direction; the subsequent eclipse of this boycott by the publicity surrounding the announcement of the Salon des Refusés; the contentious decisions of the jury of which he had been a member—all represented frustrating setbacks in a year he had hoped would witness the further exaltation of his reputation.

These experiences had not dented Meissonier's aspirations to aesthetic grandeur, however, and he was still determined to fulfill his pledge to the Académie des Beaux-Arts to produce what he called "works perhaps more worthy of its attention." To that end, by June 1863 a new painting was on his easel. Like

The Campaign of France,

it would be an epic scene from the life of Napoléon, a canvas—grand in manner and monumental in subject—that he hoped would become his masterpiece. It would feature all his familiar hallmarks, including the same scrupulous enthusiasm for history and obsessive attention to detail. It would also be by far the largest he had ever attempted. His biggest painting so far,

The Campaign of France,

had measured a modest two and a half feet wide. Attempting to cast off his reputation for miniatures, he envisaged a canvas eight feet wide by four and a half feet high. These dimensions may have paled beside the largest paintings of the century, such as Gérôme's colossal

Age of Augustus,

with its thirty-three-foot span. But they marked an eye-catching escalation for the man Gautier once called the "painter of Lilliput."

The new painting in question was to be entitled

1807: Friedland.

Instead of showing Napoléon on the brink of defeat, as in

The Campaign of France,

Meissonier chose a different moment in French fortunes—the aftermath of a battle that Adolphe Thiers had called "a splendid victory."

7

The Battle of Friedland had been fought in eastern Prussia on June 14, 1807. Eighteen months earlier, Napoléon and the Grande Armée had defeated a combined force of Austrians and Russians at Austerlitz; less than a year later, in October 1806, the Prussians had been routed at Jena. The victorious Grande Armée then marched eastward through the ensuing winter, capturing Prussian fortresses and bent on subduing Russia, France's last enemy on the Continent. Meeting a force of 60,000 Russians at the village of Friedland, on the River Alle, Napoléon won a victory so stunningly swift and decisive that Czar Alexander I had no option but to sue for peace. In an eighteen-month military expedition even more impressive, Thiers claimed, than the campaigns of Alexander the Great, Napoléon had made himself the master of an entire Continent. "Never had greater luster surrounded the person and the name of Napoléon," wrote Thiers, for whom—as for Meissonier—Friedland marked the Empire's glittering summit.

8