The Judgment of Paris (32 page)

Though they had been married for almost thirty years, Meissonier only rarely painted his wife. On one of the few occasions,

Portrait of Mme Meissonier and her Daughter,

done in 1855, he depicted Emma with bobbin and thread in hand, working at a piece of lace. The two Meissonier women are shown tranquilly following their sedentary pursuits, Emma in a chair and Therese, then fifteen, at the table with a book. Emma has long fingers and an even longer face, with refined features set in a dull and expressionless gaze. The picture of Victorian domestic respectability, she sits beneath the Mount Parnassus tapestry that features in works such as

The Etcher.

But if in

The Etcher

the figure of Apollo with his garland of laurels seems to foretell artistic triumphs awaiting Charles, in

Portrait of Mme Meissonier and her Daughter

the presence of the god above a woman sedately doing her needlework seems more than a little incongruous—perhaps even a bit ironic.

Whatever the state of his relationship with Elisa Bezanson, in 1866 Meissonier had reached a juncture in his artistic career as well as in his personal affairs. Though not deliberately boycotting the Salon as in 1863, he had decided not to show any work in the Palais des Champs-Élysées.

Friedland

was still unfinished after three years of work, and despite occasional rumors that Meissonier was about to put the work on show or sell it to a wealthy collector for an exorbitant sum—breathless reports had mentioned an American senator—the painting failed to emerge from his studio. He continued to craft his masterpiece with an intensifying series of studies, making endless sketches of lunging horses and flying hooves. The painting itself was reworked relentlessly. "Love of truth often impels me to begin something over again, after finishing it completely," he once said with reference to his work on

Friedland

6

Meissonier's obsessive labors over

Friedland were

not the only reason he was showing nothing at the Salon of 1866. He had completed a number of small works over the previous year, including one called

The Venetian Nobleman,

for which he himself had posed in a red velvet gown. But none of these works was sent to the Palais des Champs-Élysées. As a successful artist with numerous patrons, Meissonier did not need to advertise his wares at the Salon; however, his reasons for not showing work in Room M had more to do with his wish to elevate his art to more sublime heights. His ideal audience was no longer the gawping rabble who elbowed their way into the Salon or even the bankers and industrialists with their checkbooks at the ready. Rather, he was appealing to the generations to follow, who would recognize him, he hoped, as the foremost painter of his epoch. He would therefore exhibit at the Salon works such as

Friedland and The Campaign of France

or he would exhibit nothing at all.

The double act that controlled the Salon, Nieuwerkerke and Chennevières, forever experimented with their rules and regulations. In 1866 they made a major change, doubling the size of the jury for painting from twelve to twenty-four members, an enlargement that Chennevières explained would do away with "accusations of camaraderie and favoritism" that had arisen after the Salon of 1865.

7

An expanded jury would cater to a wider range of tastes while ensuring that individual jurors would possess less influence than previously. But Chennevières and Nieuwerkerke were careful to ensure that this enlarged jury remained (to quote Castagnary) an "intolerant and jealous aristocracy" by stipulating that the only painters eligible to vote were, as usual, those with membership in the Institut de France and the Legion of Honor, together with winners of medals at previous Salons. Meanwhile they retained the privilege of appointing a quarter of the painting jury themselves.

Few surprises presented themselves when the ballot boxes were opened and the votes counted on March 21. The entire membership of the 1865 Selection Committee was reelected, while new faces included Meissonier's landscapist friend Daubigny and a thirty-eight-year-old named Jules Breton, who had been enjoying popularity and acclaim with his paintings of peasants toiling in the fields. Alongside them were two history painters and muralists, Paul Baudry and Félix Barrias. The thirty-seven-year-old Baudry had won the Prix de Rome fifteen years earlier and had enjoyed immediate success after his return to Paris, titillating Salon-goers with what was to become his hallmark, female nudes in attitudes of voluptuous languor. In 1864 he had been awarded the most prestigious mural commission in France when he was selected to paint thirty-three scenes for the foyer of the new opera house that the architect Charles Gamier was building between the Boulevard Haussmann and the Boulevard des Capucines. Barrias had likewise won the Prix de Rome and then proceeded to paint ambrosial scenes from classical history onto the walls and ceilings of various public buildings. In 1866 he too was decorating Garnier's opera house, executing a scene called

The Glorification of Harmony

for the grand foyer.

In addition to the eighteen painters elected by their peers, Nieuwerkerke appointed six further jurors in order to bring the total number on the painting jury to twenty-four. They included, as usual, the critics Gautier and Saint-Victor, as well as the ornately named Jacques-Auguste-Gaston Louvrier de Lajolais. A former student of Gleyre, Louvrier de Lajolais was an interesting addition, since he had shown work at the Salon des Refusés in 1863 after the jury had rejected his work. A former

refuse'

had therefore made it onto the painting jury.

Deliberations began at the end of March, and within a few days, in a repeat of 1863, word leaked out of the Palais des Champs-Élysées of mass rejections. One newspaper reported that Édouard Manet's two paintings had been refused, though it undermined its scoop by naming the works as

Imprudence

and

Father's Opinion

—titles that sounded quite unlike anything Manet was inclined to paint.

8

When they were finally announced in the middle of April, the jury's decisions did not prove as unforgiving as three years earlier, with more than 3,000 works approved for the exhibition. But the rumor about Manet's rejection proved true as both of his works were rejected, a surprising turn of events since neither

The Tragic Actor

nor

The Fifer

seemed likely to foment controversy. Manet was apparently being punished for his work of a year earlier.

The sensation created by the rejection of the scandalous author of

Olympia

was rapidly overshadowed by an even more dramatic event: the suicide of another

refusé,

a forty-year-old painter from Strasbourg named Jules Holtzapffel. A former student of Léon Cogniet, Holtzapffel had shown work at every Salon for the previous ten years, even getting work into the Salon of 1863. Faced with rejection in 1866, he composed a despairing suicide note—"The members of the jury have rejected me, therefore I have no talent . . . I must die"—and shot himself in the head in his modest studio near the Gare du Nord.

9

Holtzapffel's violent death, as well as the publication of his suicide note, created a backlash against the supposedly heartless jurors. Groups of artists poured along the boulevards chanting "Assassins! Assassins!" while articles appeared in the newspapers denouncing what became known as "the Jury of Assassins."

10

Some of the most forceful protests came from a notorious old buffoon, the Marquis de Boissy. Furious that a portrait of himself done by Giuseppe Fagnani had failed to impress the jury, Boissy rose to his feet in the Senate and demanded the return of the Salon des Refusés. He also published a letter in a newspaper,

L'Événement,

expressing his plan to exhibit the rejected portrait together with—if Holtzapffel's family proved willing—paintings by the dead artist."

11

L'Événement

("The Event") had been launched the previous November by Hippolyte de Villemessant, owner of

Le Figaro.

Like

Le Figaro,

it dealt in scandal, intrigue, gossip, indiscretion and—if space permitted—the arts. In April 1866 it became a forum for debates over the Jury of Assassins, with Nieuwerkerke stooping to reply in its columns to the letter of Boissy and the charges of those who believed the painting jury guilty of bias, incompetence and even murder. The members were, Nieuwerkerke assured the paper's readership, "men of talent of whom France has the right to be proud and whom competent people of Europe know how to appreciate."

12

Soon after Nieuwerkerke made this stout defense, the pages of

L'Événement

began running a remarkable series of broadsides against these "men of talent" composed by an energetic and articulate twenty-six-year-old force of nature named Émile Zola. Manet and the other

refusés

of 1866 could not have found a more capable or determined advocate, nor the jurors a fiercer opponent.

* * *

"One had to be blind not to sense the vigor of this man just by looking at him," the poet Armand Silvestre once wrote of Émile Zola.

13

Raised in Aix-en-Provence, Zola was the son of a brilliant Venetian civil engineer who had built a dam across the Infernets gorge in Provence and irrigated the drought-stricken countryside with a canal—christened the Canal Zola—that delivered water to the fountains of Aix. After catching a chill on the job, Francesco Zolla (as his surname was spelled) died of pleurisy in 1847, leaving seven-year-old Émile and his mother in dire financial straits. Eventually, in 1858, the pair moved to Paris, where Zola, having twice failed his baccalauréat, tried to make his mark as a poet. There followed a torrent of long alexandrine verses, including one in honor of his father entitled "Le Canal Zola" and another, "To the Empress Eugénie," celebrating in booming couplets the military exploits of Napoléon III. Unsuccessful in these pursuits, he was forced to pawn his clothing until he had nothing to wear but a bedsheet.

Zola was not a man to buckle under rejection or hardship. In 1862 he found work in a prestigious publishing company, the Librairie Hachette, first packing books into boxes and then, when his talent for publicity was spotted, in the advertising department (where he pioneered the use of sandwich boards). He also began publishing articles on art and politics in various newspapers. A collection of short stories appeared in October 1864, followed a year later by his first novel,

The Confession of Claude,

which proved something of a

succès de scandale

thanks to raunchy bedroom scenes that attracted a series of lurid headlines ("Grave Threat to Public Morality," "Pornographic Trash," "Sex Clinic for French Citizens") and eventually the attentions of Jules Baroche, the Minister of Justice. Baroche had Zola's rooms searched and the novel examined to see if it constituted "an outrage to public and religious morals," the offense with which both Flaubert and Baudelaire had been charged in 1857. Zola was found not guilty, though the report to Baroche concluded that the novel "inspires reservations from the point of view of good taste.

14

Zola could not have been more pleased with his sudden notoriety. "Today I am ranked among those writers whose works cause trepidation," he boasted in a letter to a friend.

15

He promptly left his job with Hachette and landed a position on the scandalmongering

L 'Événement.

"Pardon me, Monsieur le Comte," Zola thundered in

L'Événement

a few days after the newspaper printed Nieuwerkerke's article praising the "men of talent" on the jury. On April 30, the day before the Salon opened, he launched his first blistering tirade, naming and shaming the twenty-four jurors for their hostilities toward and prejudices against what he called "the new movement." Making what he described as "a somewhat daring comparison," Zola described the Salon as a "giant artistic

ragout"

into which each painter poured his ingredients. But since the French public supposedly had a sensitive stomach, a team of cooks was deemed necessary to sample this eclectic stew in order to prevent "digestive disturbances" when it was dished up to the hungry public. Zola therefore proceeded to examine the qualifications and prejudices of these guardians of the public palate. "Nowadays a Salon is not the work of the artists," he claimed in the first installment, "it is the work of a jury. I am therefore concerned first of all with the jurors."

16

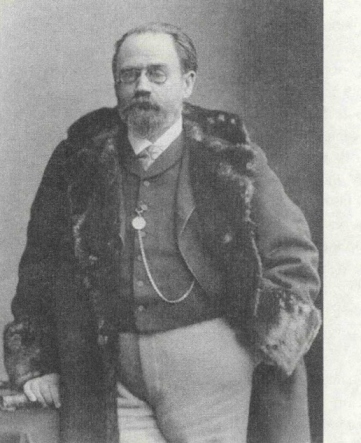

Émile Zola (Nadar)

Zola blamed the malign interference of the jury's chairman, Robert-Fleury, a "relic of romanticism" who was both the Director of the École des Beaux-Arts and, since 1865, the Director of the Académie de France in Rome. But he also denounced the newer and younger jurors, such as Jules Breton, "a young and militant painter" who had supposedly said of Manet's canvases, "If we accept works like these, we are lost." Another first-time juror, a forty-six-year-old portraitist named Édouard Dubufe, had also recoiled in horror when faced with Manet's work: "As long as I am part of a jury," Zola quoted him as saying, "I will not accept such canvases." As for another new juror, Louvrier de Lajolais, his experience of rejection in 1863 failed to make him a sympathetic judge: he supposedly boasted that only 300 of the more than 3,000 works accepted for the exhibition had received his personal seal of approval.