The Killing Room

Authors: John Manning

Ryan heard a sound. He turned. He heard it again.

Someone was in the room with him. But he could plainly see he was alone.

But then he heard the sound again. Footsteps. Not from above. Not from outside the room. But from

within

the very room.

Now there was another sound. Metal. It sounded like metal being tapped against the tiles of the floor.

“What is going on?” he whispered again, and for the first time, he felt fear.

He’d break the window. It was the only way. He picked up a heavy marble paperweight and aimed it at the glass. But even as he did so, he heard the sound again. A footstep. The tapping of metal against tile.

He glanced around quickly.

And this time he saw it.

A man. A man with dirty overalls and a straggly beard.

And in his hand the man held an enormous pitchfork, its sharp tines scraping against the floor….

Books by John Manning

ALL THE PRETTY DEAD GIRLS

THE KILLING ROOM

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

K

ILLING

R

OOM

PINNACLE BOOKS

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

Jeanette Young didn’t believe what her Uncle Howard had told her. It was all utter nonsense. If her brothers and cousins really believed such things, then they were fools. This wasn’t the Middle Ages, after all. This was 1970. And no matter what anyone tried to tell her, Jeanette refused to accept the idea that her father—her wise, beloved, dearly missed father—had ever considered such outlandish tales to be true.

“But perhaps,” Uncle Howard had said softly, taking Jeanette’s hand, “you can now better understand the manner of your father’s death.”

That had been an hour ago. Now Jeanette was alone, pondering everything her uncle had said. She threw open the window and breathed in the crisp night air. As always, the sound of waves crashing against the rocks far below the cliff soothed her. They always had, ever since she was a young girl and her father would bring her to this house to visit Uncle Howard. Those were happy days. The house had been filled with laughter. How could they all have been living with a secret like the one Uncle Howard had just revealed to her?

Uncle Howard and the others—her Aunt Margaret, her brothers, her cousins—were hoping that she would come around and accept their stories as true. That’s why they had left her alone, so she could think. But even as she reflected on all she’d been told tonight, Jeanette’s ideas didn’t change. They simply hardened.

“It’s beyond ridiculous,” she said out loud, her voice echoing in the empty parlor. “And I’ll prove it by spending the night in the room where my father died.”

It was the last weekend of September. Only a few tenacious leaves still clung to the branches of the trees. Just as the family had done every ten years for the last half century, the Young clan had gathered at Uncle Howard’s great old house on the coast of Maine. As a child and teenager, Jeanette had looked forward to the family reunions. She had enjoyed playing on the grassy lawn that stretched along the cliffs overlooking the Atlantic. With glee she had cracked the lobster claws served up by the cooks, dipping the succulent meat into the bowls of warm butter they brought out from the kitchen. Jeanette had never known about the meeting that took place on Saturday night at midnight in the parlor. Only at this gathering had she learned of that. At twenty-five, Jeanette was finally old enough to be initiated into the family secret, and to take her place in the lottery.

At the stroke of midnight, they had all gathered in the parlor. Jeanette stood beside Uncle Howard, Aunt Margaret, her brothers, and her cousins. The crackling flames in the fireplace filled the room with the fragrance of oak. Aunt Margaret had written their names on slips of paper and placed them into a wooden box. Uncle Howard, being the patriarch, reached in to select one. Everyone had watched in silence. When he pulled out Jeanette’s name, the old man’s face had gone white. “No,” he said, his voice breaking. “She’s too young.”

Her eldest brother Martin had echoed the objection. “I’ll do it in her place,” he offered, prompting a little cry from his wife, no doubt thinking of their two small children asleep in rooms upstairs.

“It would only make it worse,” Aunt Margaret said. She claimed to know such things, since she and Uncle Howard were the only ones left who remembered how the madness had begun some forty years earlier. “My father tried to shield my brother Jacob when his name was drawn,” she told the family. “Jacob had just turned sixteen. Father insisted he was too young, and so he spent the night in the room in Jacob’s place. But it was supposed to have been Jacob, since it was his name that had been chosen.” She shuddered. “And we all know how that night turned out.”

Everyone had nodded except for Jeanette. “No,” she said, “I don’t know how that night turned out.” They had told her about the lottery and revealed the secret in the basement, but they hadn’t told her this. She looked from face to face and said, “Tell me what happened that night.”

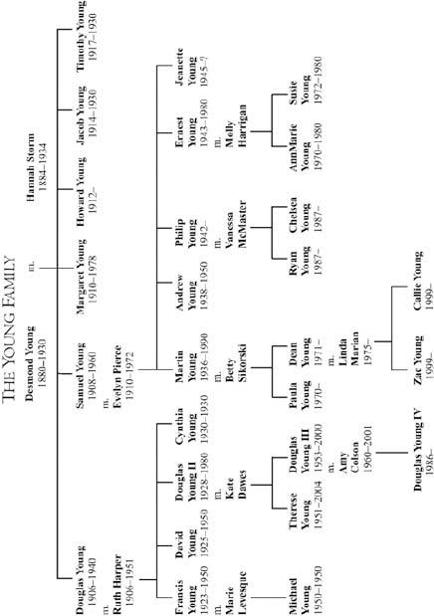

Aunt Margaret’s eyes were cold. “If you go down to the cemetery,” she said, “you’ll see there wasn’t just one death in the family that year. There was a slaughter. My father was killed. And Jacob, too, even though he never stepped a foot in that room. And my youngest brother Timothy as well, and even my newborn niece Cynthia. All as a lesson for us never again to meddle with the lottery.”

That’s when Jeanette had asked to be alone. In her hands she held a family tree that had been compiled by Aunt Margaret. She saw the death dates of all of those who had died that first night in 1930, and then the series of deaths that occurred in ten-year intervals thereafter. Her uncle Douglas in 1940. Her cousin David in 1950. And then, ten years later, her father. She looked down at his name. Samuel Young. Died 1960.

Jeanette remembered the morning they all started out for Uncle Howard’s house. She was fifteen, thrilled to be heading up the coast from their house outside Boston. She loved her uncle and thought his house was fascinating, with all its many rooms and marble staircases and outstanding views of the cliffs and the ocean. She had been excited to see her cousins. But her parents and her two older brothers were glum. At the family picnic that Saturday, the children had turned somersaults on the lawn and splashed in the surf at the bottom of the cliff, but the adults had been somber, talking quietly among themselves. That night, Jeanette was awakened after midnight by her father, slipping into her room to hug her tight. “I love you, Jen,” he’d whispered as he kissed her forehead. In the morning she learned he’d died of a heart attack in his sleep.

Now her uncle was telling her a very different story of her father’s death.

After Dad’s death, Mom had turned to drink. She had chosen not to accompany Jeanette and her brothers to Uncle Howard’s this year. Drunk, almost incoherent, she’d clung to Jeanette when she said good-bye. If the stories she’d been told were true, Jeanette could understand why her mother had gone on such a bender.

“But surely it

can’t

be what they say….”

Jeanette’s voice in the empty room seemed strange to her ears. It was as if someone else were speaking. She shivered. She looked again at the family tree, all those deaths in ten-year intervals. Then, taking a deep breath, she opened the door and called the family back into the room.

Uncle Howard came first, his face a mask of pain under his shock of white hair. Then her brothers, who’d been through all this before, guilt stricken that their names hadn’t been drawn. Then her cousin Douglas and his children, who kept their eyes away from hers. Finally there was Aunt Margaret, the bitterest of them all.

“I’ll spend the night in the room,” Jeanette announced. “And in the morning you’ll see all of this was unnecessary worry.”

“But, my dear,” Uncle Howard said, “it is important that you go in understanding what you face—”

“If what you say has any merit,” she said efficiently, “then perhaps it might be

better

if I entered the room with a healthy skepticism. If I remember my history books correctly, Franklin Roosevelt once said the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Perhaps it has been our own fear that has claimed us in the past.”

Yet even as she said the words, she knew her father had not been a man to give in to fear. She might try to cling to an idea that the deaths had all been hysterical reactions to the outrageous tales her family spun, but her theory collapsed when she applied it to her own father, a well-decorated Navy pilot in World War II who had looked death in the face many times. It hadn’t been hysterical fear that had stopped his heart in that basement room ten years ago. Standing there in front of her family, Jeanette began to accept the terrifying fact that what her uncle had told her must be true—no matter how much she still outwardly denied it.

But even if she had wanted to, there was no way to back out now. She steeled her nerves as they all bid her good-bye in the parlor. Her brothers, each in turn, embraced her, saying nothing. Even as she felt the trembling of their bodies, Jeanette did her best to push the stories Uncle Howard had told her far out of her mind. With her chin held high, she followed him across the foyer to the door leading to the basement. She refused to entertain any more thoughts of avenging spirits and haunted rooms. Uncle Howard had relayed to her the origins of what he called the family curse—a long, winding tale of madness and revenge—but she wanted none of it. She refused to keep the details in her mind. She would enter that room a modern, liberated woman, a student of philosophy near to completing her master’s thesis at Yale University, a strong, independent soul with a mind of her own. Old folktales had no power over her. It was the only way, Jeanette was now convinced, that she’d get through the night alive.

Uncle Howard pulled open a creaky old door and descended a dark staircase. Jeanette kept close behind, a dim bulb casting a pale orange light, providing barely enough illumination for them to see their way. It was at that moment that she thought of Michael. Michael—with his broad shoulders and piercing blue eyes and strong, reassuring voice. The man she hoped to marry.

“I just wish I could go with you up to Maine,” he’d said to her the day before, caressing the long auburn hair that fell to Jeanette’s shoulders. “I don’t like the idea of us being parted, even for a few days.”

“You have an important exhibit in New York,” she’d replied briskly, declining to get emotional. “If you’re ever going to be recognized as the major artist I know you’re going to be, you need to do these things.”

“It’s just so far away from you.”

Her heart was breaking, but she wouldn’t admit it. Now she wished she had been more emotional, holding Michael longer. But she had been stoic. It was always her way.

“It’s only for a weekend,” she’d told Michael. “Besides, I haven’t seen my family in so long. It’ll be nice to reconnect with all of them.”

Michael had taken her in his arms, and they had kissed. Now, in the musty basement air, Jeanette longed for her beloved’s arms.

They had reached the bottom of the steps. Uncle Howard turned to see how she was doing. Jeanette nodded that he should continue. He sighed, slowly crossing the floor of the cellar. With a key, he unlocked a door on the opposite wall. He turned and looked again at Jeanette with sad, soulful eyes.

“This is the room?” she asked boldly.

He nodded. Without any hesitation, Jeanette stepped inside. It was a plain room, rather small, no more than twenty feet across. An old sofa squatted beside a table with two chairs. It had been a servant’s bedroom back when Uncle Howard had been a boy. That’s what he had explained to Jeanette earlier. A servant girl had lived here….

And died here.

Jeanette’s eyes came to rest on the wall opposite her.

“There?” she asked her uncle. “Was that the wall?”

He nodded slowly.

That was where the poor girl had been impaled.

Beatrice. Uncle Howard had said her name was Beatrice.

And she was murdered here in this room almost half a century ago.

All of the horrors they had known since came from that fact.

Jeanette approached the wall. She stood in front of it, examining the white plaster. It had obviously been painted many times. How many coats, she wondered? How many coats did it take to cover the bloodstains left behind by that poor woman?

And by the members of the Young family whose grisly deaths had followed?

Her father had been fortunate, Uncle Howard had said. He had merely died of a heart attack. Not so her Uncle Douglas, whose wrists had been found slit, his body drained of blood. Not so her grandfather, the first after Beatrice to die in this place, whose severed head was found on one side of the room and his body on the other.

It had started to rain. She could hear the raindrops hitting against the one window in the room, a dark rectangle of glass embedded in the wall over their heads.

“I would have chosen any other name but yours, my dear,” Uncle Howard said. “I would gladly take your place in this room tonight. But in forty years of the lottery, my name has never been drawn. It is my own curse to watch as my kinfolk enter this room, one by one.” His voice choked. “Your aunt is right. We learned that first time that substituting someone for the one who was drawn will only bring more destruction.”

“I’m the first woman to spend a night here,” Jeanette said. “The first who has studied philosophy and science. This first modern Young to face this ancient force.” Her eyes fixed on her uncle. “I will survive this night. You will see.”

“Your bravery outshines us all,” he managed to say. He gripped her by the shoulders and kissed her forehead, much as her father had done a decade before. “May God preserve you.”

He hurried out of the room, closing—and locking—the door behind him.

Jeanette looked around the room. A small lamp on the table provided the only light. She sat on the sofa and folded her arms across her chest.

“Well,” she whispered. “If something is going to happen, let it happen soon.”

There was a small rumble of thunder off in the distance.

The rain was hitting the house harder now. A flicker of lightning crackled by the window. Jeanette thought once more of Michael. She would see him again. She was confident of that. If there was anything to these family legends, she’d beat them. She’d end this so-called family curse. She’d do it for her father.

She’d do it for all of them.

A huge thunderclap made her jump.

“If something’s going to happen,” she said defiantly to whoever might be listening, “bring it on! I’m not frightened of you!”

There was another loud peal of thunder, and the lamp went out.

“Damn!” Jeanette said. She didn’t want to face whatever it was in the dark.

She breathed a sigh of relief as the light flickered on again, just as another thunder boom rattled across the sky.

“I should have anticipated this,” she said. There was a small candle on the table as well, and an old book of matches. How many times had this candle been lit by fingers trembling with terror? The candle was little more than a stub. She considered lighting it, but seeing as it was so small, she didn’t want to waste the wax when the electricity was still on. Should the power go out again, she’d light it. She kept the book of matches near her hand so she could find it if the darkness returned.