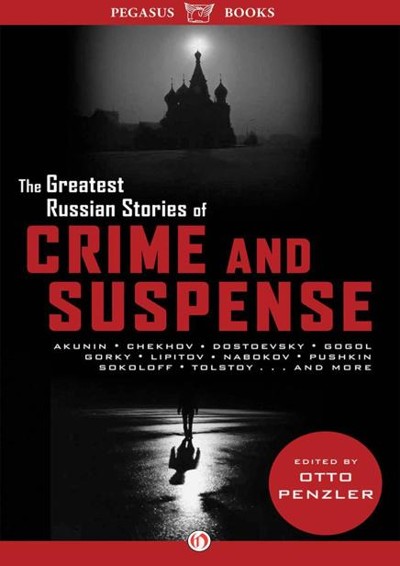

The Greatest Russian Stories of Crime and Suspense

Read The Greatest Russian Stories of Crime and Suspense Online

Authors: Otto Penzler

Tags: #Mystery, #Anthologies & Short Stories

The Greatest Russian Stories of CRIME SUSPENSE |

EDITED BY

OTTO PENZLER

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK

For Al Silverman

Gentleman, Editor Emeritus

,

Respected and Cherished Friend

CONTENTS

OTTO PENZLER

INTRODUCTION

W

hen most of us think of Russian literature, we think of the great, sprawling novels of the nineteenth century by such masters as Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the dark hopelessness of the giants of drama and the short story. We rarely associate Russian literature with the mystery story as we know it in the West—and we are right not to do so.

It is appropriate to the point of obviousness to recognize that the detective story cannot flourish in a non-democratic society. The chief protagonist in a detective story is a hero: the person who will right the wrongs perpetrated by a criminal. This is possible only in a society in which the rule of law matters, and it must matter to all strata of that society. If a government is corrupt, or dictatorial, its functionaries are, by definition, primarily focused on their own interests or in those of the government that employs them. Self-preservation, advancement and maintenance of the status quo transcends all other desires of politicians, the police, state militia and military forces in governments in which the state is superior to the individual.

The very notion of Russian detective fiction is oxymoronic, as it is a country whose citizens seldom have enjoyed individual freedom. Sinking from the oppression of the czarist regime to the horrors of the Communist police state, Russia was in no position to offer fictional police officers as the heros of mystery stories, as they were more likely than ordinary citizens to be the criminals and persecutors.

Russian crime and suspense fiction is, therefore, inevitably quite different from the Sherlock Holmes, Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler novels and short stories of England and the United States that leap to mind when we think of mystery fiction. Seldom do Russian stories involve the traditional format of a criminal activity, usually murder, committed by an unknown villain, with a detective—whether an official member of the police department, a private eye, or an amateur sleuth—called in to solve the crime, using observation and deduction.

There is a pervasive darkness to Russian crime stories that rivals the relatively new fiction genre that is often termed

noir

. The attitude of many characters often may be summarized as: Well, what can we do? Dream sequences, ghostly apparitions, supernatural occurrences, illogical choices and unresolved mysteries abound in Russian stories, which are not merely unlike Western detective fiction but are antithetical to its very definition: Crimes are abnormal, anti-social actions for which punishment is the just reward and a representative of society will serve it by employing rational methodology to identify and capture criminals.

Psychological elements produce the resolution of such early Russian crime fiction as Dostoevsky’s

Crime and Punishment

and Tolstoy’s “God Sees the Truth, but Waits.” Readers of traditional detective stories may be disappointed to learn that the question must be asked whether a crime has really been committed in such acclaimed works as Ivan Bunin’s “The Gentleman from San Francisco” and Boris Sokoloff’s “The Crime of Dr. Garine.” Supernatural denouements would never pass muster in a novel by Dashiell Hammett or John Dickson Carr, but they are not rare in the stories of Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol.

In addition to producing very little in the way of classic detective fiction, Russian publishers during the time of the czar did not make translations of English and American mystery writers available to readers. It was only after the Bolshevik Revolution created a new government that the phenomenon of pulp fiction swept across the country. What these thousands of titles lacked in literary style, they made up in adventure and excitement. Much like their American counterparts of the 1920s, these cheaply produced paperbacks featured unrealistic, super-hero crime fighters who fearlessly engaged in combat with enemies of the state. The most frequent villains were fascists and capitalists who were brought to their knees, or to their end, by secret organizations of workers. The equivalent of American “dime novels,” these hastily written potboilers sold in the tens of millions until Josef Stalin’s Communist Party decided they were too Western, as well as anti-revolutionary. “Papa Joe” believed that the purpose of literature should be to glorify the party and the state, and that singling out individual heroes and their accomplishments was philosophically opposed to that tenet.

After Stalin’s death, the Soviet government became somewhat more permissive, allowing native authors to work in the mystery genre while also translating some of the major Western writers, notably Christie, who became a best-seller. There was little similarity between the two schools, however. While Hercule Poirot could catch civil murderers by using his “little gray cells,” Soviet protagonists were invariably KGB agents or policemen who battled evil Western capitalists or spies, and their corrupt Soviet pawns, whose major goal was to bring down the state.

Mystery literature has changed a great deal under the “new” Russia. Many English and American authors are routinely translated, and so are books from other Western countries. Among Russian writers, detective novels have flourished, and readers in the former U.S.S.R. have made them their preferred choice of reading matter. In a reader survey taken in 1995, more than 32% of men and 24% of women named “detektivy” as their favorite type of book.

Among contemporary Russian mystery writers, the most successful have been Julian Semyonov, whose more than fifty somewhat uninspired novels about stolid police and KGB agents sold more than 35,000,000 copies; three were translated into English:

Petrovka .38

(1965),

Tass is Authorized to Announce

(1987) and

Seventeen Moments of Spring

(1988). His popularity has been surpassed in more recent years by Victor Dotsenko, whose Rambo-like hero is a veteran of the Afghan wars and battles the mafia; Aleksandra Marinina, described by her publisher as “the Russian Agatha Christie,” whose female protagonist, Anastasia Kamenskaya, is the ultimate armchair detective, solving crimes—like Nero Wolfe and the Old Man in the Corner—without leaving her office; Darya Dontsova, who brings an unusual element into a Russian crime novel—humor; and Boris Akunin, a serious writer who has bridged the two worlds of popular and literary fiction, producing a dozen novels in the classic tradition of nineteenth century novels and who has been translated into many languages, including English.

Like most readers, Russians find their escape from the difficulties of everyday life in literature that provides characters with whom they can identify. Since the fall of the Berlin wall and the destruction of the Iron Curtain, the oppression and seemingly random persecution of ordinary people by the Soviet government has been replaced by a criminal power structure heavily comprised of the former Communist Party officials who have merely switched allegiance from one victimizer to another. As ruthless criminal organizations flourished in the 1990s, as they continue to do today, writers gave the decent, hard-working reader a place of comfort. In popular crime novels, as the brutally powerful took advantage of their weaker neighbors, a hero emerged to do combat with those vile forces and emerge triumphant, providing a vicarious victory for the reader. While many of these adventure/crime novels lack literary merit, they have spurred great interest in and support of the mystery genre. Good defeating Evil. This cannot be a bad thing.

BORIS AKUNIN