The Knight in History (25 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Whatever these considerations weighed, Du Guesclin took the noneconomic aspect of knighthood seriously, donning the traditional white robe in the chapel of the Montmuran castle to swear the oath to serve God, defend the weak, and combat treachery. Grasping the triangular pennon that had become one of knighthood’s symbols, he chose as his battle cry, “Notre Dame—Guesclin.”

By the time he joined in the defense of Rennes in 1356, he had probably already made the transition from unpaid volunteer to paid professional soldier (in the service of Charles de Blois). The English military star was again in the ascendant, thanks to a brilliant victory won by Edward III’s oldest son, the Black Prince, and his Anglo-Gascon captains at Poitiers. The battle probably would have had few consequences except that King John II of France, a doughty but empty-headed votary of knighthood’s ideals, disdained a prudent retreat, fighting on foot until overpowered and made prisoner. The duke of Lancaster now sought to deliver a parallel blow in the Breton subwar by capturing Rennes, the capital and principal stronghold of Charles de Blois. The city’s defense was commanded by a knight and an ex-peasant. The knight, Bertrand de St. Perm, was Du Guesclin’s godfather; the former peasant, Penhouet, a self-made captain experienced in the ruses of warfare. He frustrated an enemy mining project by placing on the walls copper basins containing lead balls whose rattling pinpointed the excavation below and guided a successful countermine. When the duke of Lancaster caused a herd of pigs to be driven past the gate as a temptation to the hungry town to surrender, Penhouet had a squealing sow led out as the drawbridge was lowered. The hogs stampeded over the bridge, which was promptly raised after them.

20

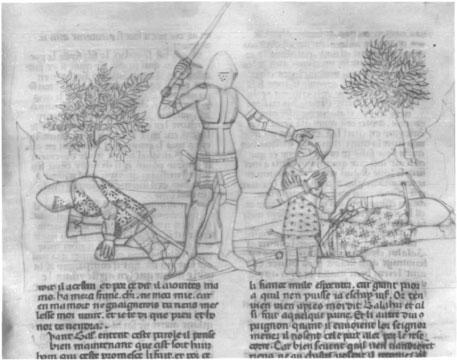

KNIGHTING ON THE BATTLEFIELD, FOURTEENTH CENTURY, A RARE BUT OCCASIONAL OCCURRENCE.

(BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS. FR. 343, F. 79)

Du Guesclin joined a small relief force gathering at Dinan, northeast of Rennes. He was watching companions playing a game of tennis when he received word that his younger brother, Olivier, had been treacherously made prisoner during a truce. Flying into a fury, he rode the forty kilometers to Lancaster’s camp, breaking in on a chess game the duke was playing with Sir John Chandos. The duke sent for Thomas of Canterbury, the English knight who had taken the prisoner. Canterbury demanded trial of the charge by judicial combat, to which Du Guesclin readily acceded. Before a large assemblage of both armies the two champions fought on horseback, with sword and dagger. Canterbury lost his sword, Du Guesclin leaped to the ground to retrieve it, Canterbury sought to ride him down, and Du Guesclin stabbed the Englishman’s horse, causing it to collapse, pinning its rider. Du Guesclin had to be dragged off his adversary, for whom Chandos and Robert Knowles pleaded mercy. Du Guesclin cooled down, and there followed a feast with the ladies.

21

Lancaster swore he would rather have five hundred archers enter Rennes in its relief than Du Guesclin, to whom he vainly offered bribes to change sides. Shortly after, Du Guesclin treated the duke to a ruse. While his own force hovered in concealment, a civilian allowing himself to be taken prisoner gave false information about the approach of a large relief army. When Lancaster took his army off to meet it, Du Guesclin plundered his camp and took the spoils into Rennes, sending word to the duke offering to return some of the wine for his dinner. Lancaster invited him to share it. Du Guesclin accepted and at dinner got involved in another duel when an English knight challenged him to break three lances. At the first shock Du Guesclin’s lance passed through his adversary’s mail, pierced his lung, and toppled him from the saddle. Such jousts—Du Guesclin fought still another before the siege was over—enlivened the monotony of siege warfare with the color of the tournament. It was doubtless a regret of Du Guesclin’s life that he did not participate in the most famous such event, the Battle of the Thirty in 1351, in which thirty chosen French knights fought thirty English, Gascon, and Breton knights before a large audience. Empty of military significance, the French triumph was cheered by trouvères, chroniclers, and other devotees of the legendary past.

Lancaster made a final attempt to carry Rennes by assault with the aid of a great wooden siege tower. Repelled, he agreed to withdraw under a face-saving formula devised by Du Guesclin that allowed the duke to enter the town long enough to plant his banner on the wall. For his successful defense, Du Guesclin was handsomely rewarded by Charles de Blois with the town and castellany of La Roche-Derrien.

While Brittany continued to suffer the depredations of war, next-door Normandy began to share them, with the outbreak of the “Navarrerie,” a war waged against the king of France by his relative the king of Navarre, who was yet another Charles, known to history as Charles the Bad. His small realm of Navarre, astride the Pyrenees, presented no threat, but Charles the Bad was also lord of a substantial piece of Normandy, including towns on the Seine that controlled Paris’s outlet to the sea. The dauphin Charles, the future Charles V (the Wise), wanted a commander for French royal forces based on Pontorson, in Brittany near the Norman border. Charles was wise enough to have fully adopted by now the English system of hiring soldiers by contract instead of relying on the old feudal levy of his father and grandfather. When Du Guesclin was recommended to him, Charles offered to put him at the head of sixty men-at-arms and archers. Du Guesclin countered by offering his own band of Bretons, who thus passed with their captain into the pay of the kingdom of France at 200 livres Tournois per year. Du Guesclin was invariably punctilious in collecting his company’s pay, not shrinking from dunning the king personally for any tardy arrears.

22

Through the next several years Du Guesclin’s reputation grew with endless sieges, surprises, sallies, and raids, interspersed with tournaments and duels. At one siege, under the eyes of the dauphin, he fell fifty feet into the moat when his scaling ladder was overthrown. Dragged from the water by his heels and revived, he demanded, “Have we taken the fort?”

23

He surprised and captured William Windsor, envoy of Edward III; surprised in his turn by Robert Knowles, he was made prisoner and had to use Windsor’s ransom to pay his own. He defeated a much larger English force (of about three hundred) and was again captured in a skirmish, this time by his former captive Hugh of Calveley. His ransom having risen to 30,000 pounds, he had recourse to the dauphin for help in paying it and ended up making a trip to London, where the duke of Orleans was prisoner, to get a needed signature. For another victory over the English he was made a knight-banneret, entitling him to double the pay of a simple knight, a larger suite, the right to recruit followers, and a prestigious square banner in place of the triangular pennon of knighthood.

24

By 1363 Du Guesclin had cleared a large part of the Cotentin, the peninsular half of Normandy, of enemy—Navarrese, English, and plain brigands. One of the latter, a notorious chief named Roger David, personally surrendered to Du Guesclin to avoid lynching by the citizens and promised to serve Charles de Blois. This chivalrous prince had become a warm admirer of Du Guesclin, who strove, with mediocre success, to honor Charles’s adjuration to “love the poor people and not allow them to be plundered and mistreated.”

25

Toward the wealthy merchants and upper clergy Du Guesclin’s attitude was quite different, his extraction of the traditional conqueror’s levy habitually seasoned with raillery.

In 1363 Charles de Blois helped arrange Du Guesclin’s marriage. The bride, many years younger than her husband, was Tiphaine Raguenel, a noble lady whose father had been one of the combatants in the Battle of the Thirty. She foretold destinies by the stars and was reputed as beautiful as she was learned, in double contrast to the bridegroom, who expended more labor writing his name than in delivering a sword thrust and was reputed as ignorant as he was ugly.

26

From the beginning of 1364 Du Guesclin received a new, enlarged authority from the royal power. King John II had died in comfortable captivity in London, where his anachronistic devotion to the ideals of knighthood had commanded the respect even of pragmatic Edward III. The former dauphin, succeeding to the throne as Charles V, was the reverse of his physically strong, mentally weak father and had already demonstrated the capacity to govern his war-afflicted country. Well acquainted with Du Guesclin’s worth, he made him “captain-general of the bailliage of Caen and the Cotentin” and also lieutenant for the duke of Orleans for the lands between the Seine and Brittany, territory comprising most of the militarily sensitive area west of Paris. Charles the Bad of Navarre, recently quiet, had again renewed his hostility to the royal power, which had frustrated his desire to add the splendid ducal crown of Burgundy to his titles. It became imperative for Paris’s safety to break the Navarrese hold on the Seine basin, commanded by the towns of Mantes and Meulan.

On a Sunday morning (April 7, 1364), Du Guesclin seized Mantes by a ruse. One hundred of his men waited stealthily outside till the gate was opened to allow the first wagon of the day to depart. Seizing it to block the gate, they spread through the neighboring streets, creating panic. By the time Du Guesclin could enter with the main body of his army, terrified citizens were jumping from the ramparts or fleeing in boats in the Seine. The Breton intruders wasted no time. According to a chronicler, Du Guesclin “had it proclaimed through the town that no one was to hurt woman or child, but the town was already pillaged.”

27

When three days later Du Guesclin and another captain forced entry into Meulan, whither most of the refugees from Mantes had fled, a second sack followed.

28

The two events did much to credit the popular saying that Breton and brigand were two words for the same thing.

*

The looting included theft of jewels and money belonging to the dowager Queen Blanche, whom Charles V hastily indemnified as recorded in a document that mentions prisoners taken by “our beloved and loyal knight, Bertran du Claequin,” elsewhere referred to as “our loyal knight and chamberlain Bertren de Gueskin.”

29

The offensive was a technical violation of a truce. Protesting that he was the victim of royal aggression, Charles the Bad planned a daring, and potentially devastating, counterstroke. Charles V was preparing his coronation journey to Rheims. Charles the Bad conceived the idea of assembling an army west of Paris, intercepting the procession as it returned to the capital, and capturing the king. To execute the coup he recruited the Captal (Gascon: “lord”) de Buch, a famous and colorful Gascon captain who was one of the chief victors of the battle of Poitiers. The Captal concentrated his force of three to four thousand Gascons, Normans, English, and undefined “brigands” at Evreux, northwest of Paris. Du Guesclin blocked him at Cocherel, where a fierce combat took place. At one moment the two leaders met face to face. The Captal split Du Guesclin’s helmet with a blow of his mace, but he was himself unhorsed and taken. His English lieutenant, John Jouel, was mortally wounded, and his army slaughtered or scattered. Du Guesclin followed up his victory by storming the fortress of Valognes, and Charles the Bad gave up the war, agreeing to trade his piece of Normandy for token compensation in the south.

30

Later that same year (1364) Du Guesclin took part in another rare field battle, this time with less fortunate results. The king of France no longer needing him, his services were sought once more by Charles de Blois, still locked in his Breton war, now with the son of his original rival. When the two armies met at Auray on the south coast of Brittany, young Jean de Montfort had the benefit of English and Gascon commanders as well as troops and profited from the advice of Sir John Chandos to husband his reserve and win the hard-fought battle. Du Guesclin, commanding Charles’ left wing, was the last holdout and was once more taken prisoner, wounded and streaming with blood. More important, through accident or design, Charles de Blois was slain on the battlefield instead of being captured. This event, rather than the outcome of the battle, determined the outcome of the war, because, unlike his Montfort rival, Charles left no heir.

31

Du Guesclin’s ransom having risen to 40,000 florins, he again appealed to Charles V for help in paying it, temporarily relinquishing his county of Longueville, bestowed as a reward for the victory of Cocherel. Charles V was glad to help since he again needed his Breton war dog, this time for an unusual service. The general lull that had set in on all fronts had left an unpleasant and dangerous legacy in the form of dozens of “free companies” of unemployed soldier-brigands who roamed the countryside pillaging, or even seized castles and imposed their reign of terror on whole districts. Local authorities, instead of joining forces against them, bribed the intruders to go elsewhere, and the major military effort required to extirpate them was beyond Charles’s financial means. A new dynastic civil war across the Pyrenees offered an attractive solution. Henry of Trastamare, an illegitimate son of the late king of Castile, was contesting the throne held by his unpopular half-brother Pedro the Cruel. Charles V foresaw a dividend in the acquisition of a Spanish ally, and the enterprise promised above all to get the companies out of France. The king thought that Du Guesclin’s name might suffice to attract the brigand captains, and such proved to be the case. In the words of a chronicler, “the said companies, English, French, Norman, Picard, Breton, Gascon, Navarrese, and others, men who lived off war, left the kingdom of France.”

32