The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (58 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

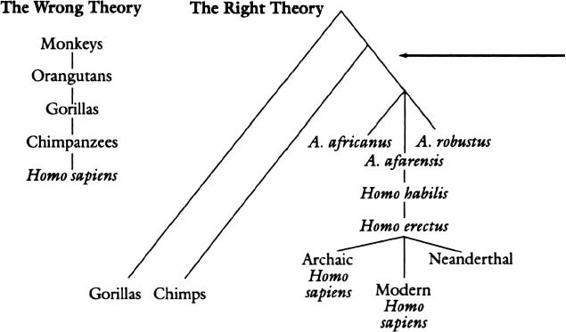

Zooming in on our branch, we see chimpanzees off on a separate sub-branch, not sitting on top of us.

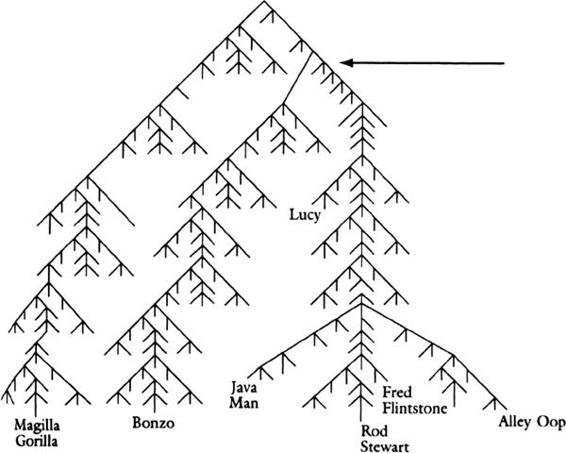

We also see that a form of language could first have emerged at the position of the arrow, after the branch leading to humans split off from the one leading to chimpanzees. The result would be languageless chimps and approximately five to seven million years in which language could have gradually evolved. Indeed, we should zoom in even closer, because species do not mate and produce baby species; organisms mate and produce baby organisms. Species are an abbreviation for chunks of a vast family tree composed of individuals, such as the

particular

gorilla, chimp, australopithecine,

erectus

, archaic

sapiens

, Neanderthal, and modern

sapiens

I have named in this family tree: So if the first trace of a proto-language ability appeared in the ancestor at the arrow, there could have been on the order of 350,000 generations between then and now for the ability to have been elaborated and fine-tuned to the Universal Grammar we see today. For all we know, language could have had a gradual fade-in, even if no extant species, not even our closest living relatives the chimpanzees, have it. There were plenty of organisms with intermediate language abilities, but they are all dead.

Here is another way to think about it. People see chimpanzees, the living species closest to us, and are tempted to conclude that they, at the very least, must have some ability that is ancestral to language. But because the evolutionary tree is a tree of individuals, not species, “the living species closest to us” has no special status; what that species is depends on the accidents of extinction. Try the following thought experiment. Imagine that anthropologists discover a relict population of

Homo habilis

in some remote highland.

Habilis

would now be our closest living relatives. Would that take the pressure off chimps, so it is not so important that they have something like language after all? Or do it the other way around. Imagine that some epidemic wiped out all the apes several thousand years ago. Would Darwin be in danger unless we showed that monkeys had language? If you are inclined to answer yes, just push the thought experiment one branch up: imagine that in the past some extraterrestrials developed a craze for primate fur coats, and hunted and trapped all the primates to extinction except hairless us. Would insectivores like anteaters have to shoulder the proto-language burden? What if the aliens went for mammals in general? Or developed a taste for vertebrate flesh, sparing us because they like the sitcom reruns that we inadvertently broadcast into space? Would we then have to look for talking starfish? Or ground syntax in the mental material we share with sea cucumbers?

Obviously not. Our brains, and chimpanzee brains, and anteater brains, have whatever wiring they have; the wiring cannot change depending on which other species a continent away happen to survive or go extinct. The point of these thought experiments is that the gradualness that Darwin made so much about applies to lineages of individual organisms in a bushy family tree, not to entire living species in a great chain. For reasons that we will cover soon, an ancestral ape with nothing but hoots and grunts is unlikely to have given birth to a baby who could learn English or Kivunjo. But it did not have to; there was a chain of several hundred thousand generations of grandchildren in which such abilities could gradually blossom. To determine when in fact language began, we have to look at people, and look at animals, and note what we see; we cannot use the idea of phyletic continuity to legislate the answer from the armchair.

The difference between bush and ladder also allows us to put a lid on a fruitless and boring debate. That debate is over what qualifies as True Language. One side lists some qualities that human language has but that no animal has yet demonstrated: reference, use of symbols displaced in time and space from their referents, creativity, categorical speech perception, consistent ordering, hierarchical structure, infinity, recursion, and so on. The other side finds some counterexample in the animal kingdom (perhaps budgies can discriminate speech sounds, or dolphins or parrots can attend to word order when carrying out commands, or some songbird can improvise indefinitely without repeating itself) and then gloats that the citadel of human uniqueness has been breached. The Human Uniqueness team relinquishes that criterion but emphasizes others or adds new ones to the list, provoking angry objections that they are moving the goalposts. To see how silly this all is, imagine a debate over whether flatworms have True Vision or houseflies have True Hands. Is an iris critical? Eyelashes? Fingernails? Who cares? This is a debate for dictionary-writers, not scientists. Plato and Diogenes were not doing biology when Plato defined man as a “featherless biped” and Diogenes refuted him with a plucked chicken.

The fallacy in all this is that there is some line to be drawn across the ladder, the species on the rungs above it being credited with some glorious trait, those below lacking it. In the tree of life, traits like eyes or hands or infinite vocalizations can arise on any branch, or several times on different branches, some leading to humans, some not. There is an important scientific issue at stake, but it is not whether some species possesses the true version of a trait as opposed to some pale imitation or vile impostor. The issue is which traits are

homologous

to which other ones.

Biologists distinguish two kinds of similarity. “Analogous” traits are ones that have a common function but arose on different branches of the evolutionary tree and are in an important sense not “the same” organ. The wings of birds and the wings of bees are a textbook example; they are both used for flight and are similar in some ways because anything used for flight has to be built in those ways, but they arose independently in evolution and have nothing in common beyond their use in flight. “Homologous” traits, in contrast, may or may not have a common function, but they descended from a common ancestor and hence have some common structure that bespeaks their being “the same” organ. The wing of a bat, the front leg of a horse, the flipper of a seal, the claw of a mole, and the hand of a human have very different functions, but they are all modifications of the forelimb of the ancestor of all mammals, and as a result they share nonfunctional traits like the number of bones and the ways they are connected. To distinguish analogy from homology, biologists usually look at the overall architecture of the organs and focus on their most useless properties—the useful ones could have arisen independently in two lineages

because

they are useful (a nuisance to taxonomists called convergent evolution). We deduce that bat wings are really hands because we can see the wrist and count the joints in the fingers, and because that is not the only way that nature could have built a wing.

The interesting question is whether human language is homologous to—biologically “the same thing” as—anything in the modern animal kingdom. Discovering a similarity like sequential ordering is pointless, especially when it is found on a remote branch that is surely not ancestral to humans (birds, for example). Here primates are relevant, but the ape-trainers and their fans are playing by the wrong rules. Imagine that their wildest dreams are realized and some chimpanzee can be taught to produce real signs, to group and order them consistently to convey meaning, to use them spontaneously to describe events, and so on. Does that show that the human ability to learn language evolved from the chimp ability to learn the artificial sign system? Of course not, any more than a seagull’s wings show that it evolved from mosquitos. Any resemblance between the chimps’ symbol system and human language would not be a legacy of their common ancestor; the features of the symbol system were deliberately designed by the scientists and acquired by the chimps because it was useful to them then and there. To check for homology, one would have to find some signature trait that reliably emerges both in ape symbol systems and in human language, and that is not so indispensable to communication that it was likely to have emerged twice, once in the course of human evolution and once in the lab meetings of the psychologists as they contrived the system to teach their apes. One could look for such signatures in development, checking the apes for some echo of the standard human sequence from syllable babbling to jargon babbling to first words to two-word sequences to a grammar explosion. One could look at the developed grammar, seeing if apes invent or favor some specimen of nouns and verbs, inflections, X-bar syntax, roots and stems, auxiliaries in second position inverting to form questions, or other distinctive aspects of universal human grammar. (These structures are not so abstract as to be undetectable; they leapt out of the data when linguists first looked at American Sign Language and Creoles, for example.) And one could look at neuroanatomy, checking for control by the left perisylvian regions of the cortex, with grammar more anterior, dictionary more posterior. This line of questioning, routine in biology since the nineteenth century, has never been applied to chimp signing, though one can make a good prediction of what the answers would be.

How plausible is it that the ancestor to language first appeared after the branch leading to humans split off from the branch leading to chimps? Not very, says Philip Lieberman, one of the scientists who believe that vocal tract anatomy and speech control are the only things that were modified in evolution, not a grammar module: “Since Darwinian natural selection involves small incremental steps that enhance the present function of the specialized module, the evolution of a ‘new’ module is logically impossible.” Now, something has gone seriously awry in this argument. Humans evolved from single-celled ancestors. Single-celled ancestors had no arms, legs, heart, eyes, liver, and so on. Therefore eyes and livers are logically impossible.

The point that the argument misses is that although natural selection involves incremental steps that enhance functioning, the enhancements do not have to be an existing module. They can slowly build a module out of some previously nondescript stretch of anatomy, or out of the nooks and crannies between existing modules, which the biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin call “spandrels,” from the architectural term for the space between two arches. An example of a new module is the eye, which has arisen de novo some forty separate times in animal evolution. It can begin in an eyeless organism with a patch of skin whose cells are sensitive to light. The patch can deepen into a pit, cinch up into a sphere with a hole in front, grow a translucent cover over the hole, and so on, each step allowing the owner to detect events a bit better. An example of a module growing out of bits that were not originally a module is the elephant’s trunk. It is a brand-new organ, but homologies suggest that it evolved from a fusion of the nostrils and some of the upper lip muscles of the extinct elephant-hyrax common ancestor, followed by radical complications and refinements.

Language could have arisen, and probably did arise, in a similar way: by a revamping of primate brain circuits that originally had no role in vocal communication, and by the addition of some new ones. The neuroanatomists A1 Galaburda and Terrence Deacon have discovered areas in monkey brains that correspond in location, input-output cabling, and cellular composition to the human language areas. For example, there are homologues to Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas and a band of fibers connecting the two, just as in humans. The regions are not involved in producing the monkeys’ calls, nor are they involved in producing their gestures. The monkey seems to use the regions corresponding to Wernicke’s area and its neighbors to recognize sound sequences and to discriminate the calls of other monkeys from its own calls. The Broca’s homologues are involved in control over the muscles of the face, mouth, tongue, and larynx, and various subregions of these homologues receive inputs from the parts of the brain dedicated to hearing, the sense of touch in the mouth, tongue, and larynx, and areas in which streams of information from all the senses converge. No one knows exactly why this arrangement is found in monkeys and, presumably, their common ancestor with humans, but the arrangement would have given evolution some parts it could tinker with to produce the human language circuitry, perhaps exploiting the confluence of vocal, auditory, and other signals there.