The Last Boy (14 page)

Authors: Jane Leavy

In 1953, a row of six similar houses on Fifth Street faced the left field wall of the stadium. A swath of grass—“a cut-through,” Dunaway called it—ran behind the houses and parallel to the sidewall of 434 Oakdale Place. “Something told me to look in the back. I went through the little cut.”

In the fall of 2008, the lot once occupied by the Fifth Street row houses was empty, enclosed by chain-link fence with a sign proclaiming Howard University’s intention to rebuild on the site:

COMING SOON

,

NEW HOMES AT HISTORIC LEDROIT PARK

. The chain link made it impossible for us to reach the backyard of 434 Oakdale Place where Patterson said Dunaway had led him to the ball. The yard was enclosed by a picket fence; the back section ran parallel to an alley, where another wooden fence once kept the black residents of Howard Town from entering LeDroit Park.

I asked Dunaway to show me how far back behind the house he had found the ball. “Under the window,” he said, pointing to a second-story side window, which was at least twenty-five feet closer to Oakdale Place and to the stadium than Patterson’s declared location. Which meant the ball had never reached the backyard of 434 Oakdale Place at all.

“No,” he said. Never said it had.

Turning, he pointed to the now-empty corner lot where each of the demolished row houses had had a small fenced-off yard. “I looked in everybody’s yard ’til I went to this particular yard and found it,” he said. The ball was sitting against the back of the house—probably the second or third from the corner—in a pile of dead leaves. “Standing out,” he said.

He took the ball to an usher he had spoken with on his way out of the ballpark. “He said, ‘You found that ball? Damn, you is kidding.’ He said, ‘C’mon, I’m goin’ to take you ’round to the clubhouse.’”

In

All My Octobers

, Mantle wrote, “I think the kid just showed up at the clubhouse wanting to sell the ball or get an autograph.”

That’s pretty much what happened, Dunaway said. The usher escorted

corted him to the visitors locker room along the third base line, where they were greeted by a clubhouse attendant, who summoned someone official-looking. Dunaway assumed he was a reporter because he had a pad and pencil and wrote down everything he said. The usher provided the bona fides. “He said, ‘This is the fella who caught Mickey Mantle’s ball,’” Dunaway said. “I gave him the whole outlook.”

But he never mentioned 434 Oakdale Place. Nor did he take anyone to the spot where he had found the ball. “I told him I found it on Fifth Street behind a guy’s house. I told him where to go look for it himself.”

What did the man look like? “White,” he said. “He shook my hand. He said it might have been one of the longest ever.”

Dunaway handed over the prize and was promised a ball autographed by the slugger that never arrived in the mail. “He gave me a hundred dollars,” he said. “The guy told me how famous I would be for catching the ball. I was more excited about the money than about being famous. That was a lot of money back then.”

Newspaper reports of a much smaller bounty made him indignant. “Not no dollar. He gave me a ball then, too. It was autographed by four or five players. I gave that ball to one of my grandnephews. He was playing baseball with that as he was growing up.”

A photographer took his picture with the ball before he relinquished it. Friends told him later that their fathers had seen it in out-of-town papers. He looked for it in the

Washington Post

the next morning and was disappointed not to find himself there. (No photograph could be located in the archives of the

Post

, the

Washington Star

, the

Afro-American

, the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., or the Library of Congress.)

That afternoon, his uncle Willie, a railroad porter who lived with the family when he wasn’t working, took him shopping on Seventh Street. He bought himself some khaki pants, socks, shirts, tennis sneakers, and a couple of beers for his uncle. When he got home he had “some ’splainin’” to do. He spent the rest of the money on candy and pinball and taking neighborhood girls to Tom Mix shows at the Dunbar Theater.

He finished the school year, but sixth grade was his last. That summer, he was caught stealing and was sent to Blue Plains in southeast Washington, D.C., once called the Industrial Home for Colored Children. He ran away that fall. It wasn’t any harder than sneaking into Griffith Stadium.

He didn’t go back to school, and he didn’t go back to the old neighborhood. He didn’t want any part of the truant officers looking for him in LeDroit Park. He lived on the streets and with an uncle in Anacostia who let his mother know he was all right. He spent afternoons at a police boys’ club on Florida Avenue where no one asked questions, worked at a local shoeshine stand, and set pins at the Lucky Strike bowling alley.

Trouble led to more trouble and incarceration in a facility for juvenile offenders in Ohio, where he learned how to do laundry, to say the rosary, and that he didn’t want to spend any more time in jail. He was twenty years old and had five months of parole to serve when he was released after five years.

He worked in hotel laundries around the nation’s capital until the mid-1980s. He survived on frugality, good luck—he hit a couple of $5,000 Four Ways in Atlantic City—and “the grace of God,” his brother-in-law Elder Walter McCollough said.

He donated money to every Catholic charity that asked for help and filled his apartment with the rosary beads he received. He never married, which he regretted, and had a daughter, whose name he could not spell. Most of his friends from the old neighborhood were dead and gone when we met. But the memory of the day he hit the jackpot at Griffith Stadium remained vivid. “One big day,” he said.

The best day of his life.

He died on March 3, 2010, due to complications from diabetes, gout, and pneumonia. He was seventy-one years old.

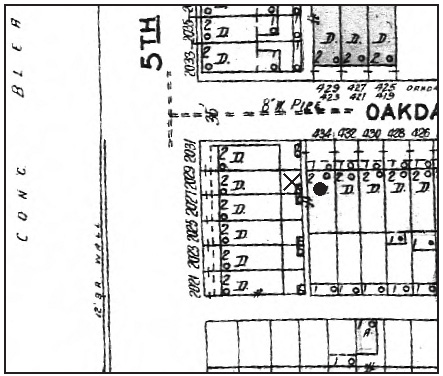

In the spring of 2008, Alan Nathan, professor emeritus of physics at the University of Illinois–Champaign-Urbana and chair of the Society for American Baseball Research’s Science and Baseball Committee, succumbed to my entreaties and clambered to the roof of Howard University Hospital to test the prerogatives of memory and place against the hard discipline of science. Armed with my new laser range finder, historical photographs, Google Earth images of the neighborhood with dimensions of the old stadium superimposed on a grid, Sanborn Insurance maps from

1953, building permits for the demolished Fifth Street row houses, newspaper accounts, and a very good head for math, Nathan set out to establish the most plausible fate of the ball. Unlike Red Patterson, he also had a tape measure.

The myth of the Tape Measure Home Run was consecrated and perpetuated by Mel Allen’s 1969 re-creation recorded by for an album celebrating

One Hundred Years of Baseball History

, which was replicated on a 1973 Yankees record—

Fifty Years of Sounds

—and given to every fan at the last game before the Stadium closed for renovations. It was later rebroadcast on

This Date in Baseball History

and

This Week in Baseball

. Neither his call of the game nor Bob Wolff’s D.C. broadcast had been recorded. Allen’s bellowed re-creation became accepted fact: “We have just learned that Yankee publicity director Red Patterson has gotten hold of a tape measure and he’s going to go out there to see how far that ball actually did go.”

But when Bill Jenkinson, a baseball historian and author with a penchant for the long ball, confronted the spinmeister on the matter of the tape measure in the early 1980s, Patterson cheerfully admitted he had never had one. He also told Jenkinson he had never claimed the boy told him he saw the ball land on a fly. He had paced off the distance with his size eleven shoes. Marty Appel, who later became the Yankees’ director of publicity, told Patterson his shoes belonged in the Hall of Fame.

Previous scientific attempts to ascertain the actual flight of the ball have not been universally well received in the world of Mantleology. In 1990, Yale professor Robert K. Adair published the bible of baseball science,

The Physics of Baseball

, devoting an entire chapter to the Tape Measure Home Run. Twenty years later he stood by his original conclusion that the ball had traveled 506 feet, with a margin of error no more than 5 feet. “The number 565 is pure fiction,” Adair told me. “It was where they picked the ball up after it rolled across the street.”

Jenkinson conducted his own analysis, relying on both anecdotal accounts and scientific data. His conclusion: the ball traveled no farther than 515 feet and probably 10 feet less than that. When his findings were published in 2008 by Yahoo! Sports, the baseball blogosphere reverberated with cyberhowls. Mantle devotee Randall Swearingen denounced

Jeff Passan’s column as “a malicious prosecution” of The Mick.

MICKEY’S HISTORIC HOMER ON TRIAL!

From the roof of the hospital, one thing was immediately apparent to Alan Nathan. The ball Mantle hit off Chuck Stobbs could not have traveled 565 feet in the air or rolled or bounced that far from home plate. Nor could Patterson have walked a straight line in his size elevens from the backyard of 434 Oakdale Place to the back of the stadium, as he told reporters. According to the 1953 Sanborn map, the houses on Fifth Street and the fences behind them would have obstructed both his path and that of the ball.

Figuring out what

could

have happened was more challenging, given the protean nature of the urban landscape. Blueprints of the stadium could not be located. Clark Griffith, the surviving member of the stadium’s baseball dynasty, had no records. The exact dimensions of the scoreboard were in some dispute. No building permit for its construction or for the concrete bleachers was on file with the District of Columbia. The exact location of home plate was unknown. “Mickey’s tree,” the landmark oak beyond the center field fence, had been sacrificed to progress—a hospital parking lot.

However, the corner of Fifth and V streets and the building behind the third base line were unchanged. Using my range finder and those fixed points, Nathan located home plate on the 1953 map “to within a circle of radius of about three feet.”

Our hope had been to use the range finder to measure the distance from home plate to the reported landing zone. But the hospital’s roof made that impossible. Resorting to old-fashioned arithmetic, Nathan calculated a straight-line distance of approximately 557 feet from home plate to the backyard of 434 Oakdale Street. But he had already rejected Patterson’s claim as “crazy” and now discounted Adair’s analysis because it underestimated the effect of the spin of the ball and failed to account for the Fifth Street row houses.

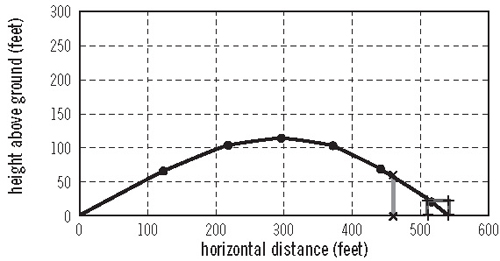

Unimpeded, Nathan concluded, the ball could have traveled as far as 535 to 542 feet—“A lot further than Adair says.” But the houses were in its way.

Our next step was to try to find a scenario that matched Dunaway’s description and that also had a basis in science. For more than a year,

Nathan consulted other physicists, including Adair and SABR members devoted to the study of demolished ballparks. He reviewed all the anecdotal evidence and weather data: Bill Abernathy’s recollection that the wind picked up just as the pitch was thrown; Lou Sleater’s dugout observation that the ball went “straight up” like “it was going to be a pop-up to the shortstop and just took off”; and third baseman Eddie Yost’s testimony that the ball hit halfway up the Mr. Boh sign, above the words

OH, BOY, WHAT A BEER,

and then veered right at a 20- to 30-degree angle. Nathan considered—and rejected—several hypotheses. Could the ball have ricocheted off Mr. Boh, then bounced on the pavement of Fifth Street and

over

the row houses into the backyard of 434 Oakdale Street? No; the proximity of the buildings and the angle of descent precluded that. Could it have pecked Mr. Boh on the cheek on the way out of the ballpark, landed on Oakdale Place, and taken a hard right into the cut-through? Nope, not unless it was more magical than the Kennedy bullet. Nathan concluded that “the only reasonable scenario is one whereby the ball hits the roof of a house on Fifth Street on the fly, then bounces off into the backyard.”

Certified 1959 Sanborn Map showing the corner of Fifth Street and Oakdale Place, behind the left field wall at Griffith Stadium, Washington, D.C. A fence that once kept black residents out of the all-white community of LeDroit Park ran east-west in the alley behind 434 Oakdale Place.

• Red Patterson: backyard of 434 Oakdale Place

× Alan Nathan: backyard of 2029 Fifth Street NW, now demolished

Credit: Environmental Data Resources, Inc.

Proving it was another matter. The quest for exactitude was compromised by insufficient information about the wind speed 60 feet above field level and the dimensions of the beer sign. The groundskeeper and the club secretary offered conflicting reports: one said it measured 55 feet

high, the other said 48 feet. Both agreed that the ball had hit at least 6 feet above the back wall of the stadium.

Hypothetical trajectory of the Tape Measure Home Run showing the edge of the Mr. Boh sign and the second of the attached row houses on Fifth Street NW

Credit: Alan M. Nathan