The Last Boy (53 page)

Authors: Jane Leavy

The replication of the biomechanical ideal, what man-made machines can do absent annoying human deviation, is complicated by physical idiosyncrasy. “Style and technique are vastly different,” said Mike Epstein, who runs a hitting school in Denver, Colorado. “Style is the individual and the technique is universal. All the great, productive hitters conform to the same technique. Their bodies fit into what I call that envelope. Before a hitter can get into that envelope, he goes through all the different gyrations that make him feel comfortable: hands high, hands low, hands out, hands in, bat straight up, flat bat, closed stance, open stance, wide stance, narrow stance, stride, no stride. If a good technique doesn’t conform to the laws of physics, then you’re essentially rolling a boulder uphill.”

Viewing Mantle in kinetic form strips away nuance and reveals what was universal in his swing and also what differentiated him. To facilitate an understanding of Peavy’s analysis, he created kinetic snapshots to insert into the text below. To view the full set of Mantle kinematics and the film clips from which they were drawn, go to

www.peavynet.com

or

www.janeleavy

.com.

From a coach’s perspective, was Mantle’s swing perfect? “Absolutely not,” Peavy said, “but it was a thing of raw beauty, completely uninhibited,” and “strikingly modern” in the way he shifted his weight to recruit all his available power, and positioned his elbow and moved his hands. “Add a top-hand release,” he says, and you have A-Rod or Ken Griffey.

“I think he just stumbled on a real modern swing. Nobody was looking for that then. Nobody

knew

to look for it. This was pure, bluecollar, farm-boy aggressiveness. I can’t think of anybody as naturally aggressive. He was allowed to be naturally aggressive. There are no similar guys. Especially from the left side, I can’t think of anybody as violent as he was. Unbridled aggression is what made Mantle Mantle.”

That zealousness was aided and abetted by sheer athleticism and a

physique tailored for baseball. “His proportions are classical, ideal,” Peavy said. “The length of his arms and legs enabled him to implement a modern swing. He’s not particularly square; not particularly long in the torso; he wasn’t a fireplug. He was a truly gymnastically proportioned athlete. If you wanted to build a baseball player from scratch, Mickey Mantle was it. He was built for this.”

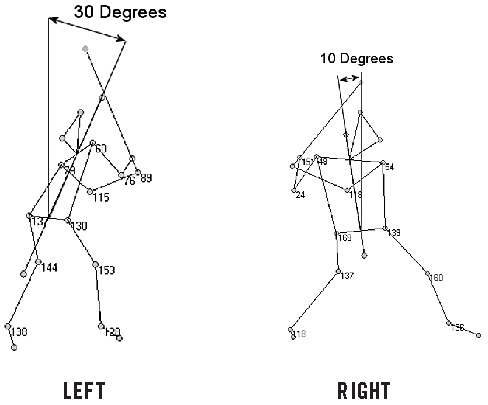

Mantle’s right-handed swing was natural, easier on his body, and easier for him to perfect. He batted twice as often left-handed but hit the ball harder and more effortlessly right-handed. He was more energy-efficient as a right-handed hitter but his posture, batting left-handed, was more classical. Right-handed, he stood upright; left-handed, he assumed a feral crouch. Right-handed, his swing was compact; left-handed his swing was like a storm, a vicious prairie updraft.

“Brutish,” Peavy called it. It had to be to generate the same power that came naturally right-handed. “He had to apply more force with his legs,” Peavy said, and he had to work harder to achieve the same results.

“He looked beautiful when he attacked the ball both ways, but there was a decided difference,” Osteen said. “He may have been just as aggressive right-handed but not near as violent.”

Left-handed hitters tend to lean back in anticipation of the curveballs and sliders righty pitchers deliver down and in. Right-handed hitters tend to stand more upright because the breaking balls they face from right-handed pitchers are higher when they break across the plate. In this regard, Mantle conformed to the norm. His left-handed stance was sharply canted backward, an axis of 18 to 20 degrees, a necessary counterbalance to the vehemence of his swing. “Otherwise he would have fallen over,” Peavy said.

Batting right-handed, his axis was only 10 degrees off vertical, and it became more so as his body moved forward in space. His shoulders and hips stayed level, enabling all the momentum he generated to rotate around a solid axis. “Like a barbershop pole,” Osteen said.

When everything is working as it should, a batter’s hips rotate at 760 degrees per second. “Think of a spinning top,” Peavy said. “When the axis is steady, the top spins like crazy. When the axis starts to wobble, the top rapidly loses speed and efficiency and finally stops spinning.”

An average major league fastball drops three feet on its 60-foot, 6-inch journey to home plate, descending at a trajectory of 10 to 15 degrees. By swinging upward at approximately the same angle, a hitter increases

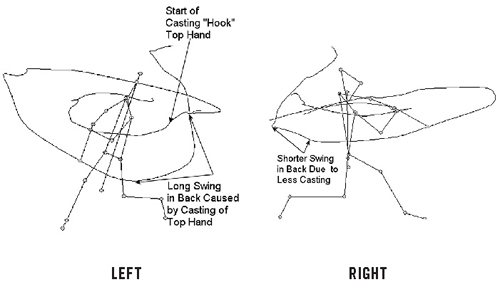

the window of opportunity for making contact with the ball. That’s why coaches preach swinging level to the pitch, not to the ground. The long, flat trajectory visible in the kinetic of Mantle’s right-handed bat path meant, in coach speak, that he was “long in the usable plane of the pitch.” Peavy estimates his hitting zone was 2 to 3 feet on the right side and 10 to 20 percent less when batting left-handed.

No hooks or loops detoured this right-handed swing. Mantle’s hands moved with speed and an economy of motion, traveling through the hitting zone, Peavy estimates, in .11 to .14 seconds. “Tremendous bat speed,” Osteen said.

And, in the argot of hitting coaches, he kept his hands inside the ball, which means he kept them to himself. In so doing he was obeying what physicists call the law of conservation of angular momentum, which dictates that a rotating body will spin as long and as fast as it can, absent protrusions. That’s why a figure skater spins faster when his hands are held close to his body, and why a batter does not want to cast his hands away from his body the way a fisherman does.

Even the slightest hook diminishes bat speed. In the kinetic of Mantle’s left-handed bat path, a slight hook is visible just before the bat dipped down toward the catcher. The looping, lasso-like uppercut meant that his bat was not nearly as long in the plane of the ball. Peavy estimates the extra length added perhaps .2 of a second to the time it took his hands to move through the hitting zone. “That’s why he had to start his swing earlier,” Peavy said.

And that made him more vulnerable to an off-speed pitch. “It’s like, ‘Oh, shit, now I gotta wait for that big-ass curve,’” Peavy said. “And he can’t do it because he’s already moving his hands for the fastball. It’s why pitchers can sometimes make him look stupid.”

Of course, they knew that. “That’s why we throw slow curves to almost all of the low-ball, back-legging fastball hitters,” Osteen said.

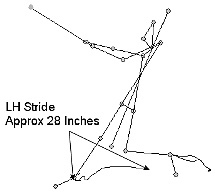

Mantle’s unbridled aggression was best expressed and most visible in the length of his left-handed stride, which measured as much as 28 inches, a stunningly long distance, Peavy says, for his era and for his height. Ken Griffey’s stride was approximately half that length. In most mortals, a 2-foot stride would cause a precipitous and calamitous drop in the center of gravity. Mantle minimized that drop through sheer athleticism and balance, moving forward, Peavy says, “like a big cat.”

Maintaining a level center of gravity is essential if you want to keep your bat on the plane of the ball. “If your center of gravity dips, your eyes and head dip, making it much harder to put your hands in the right place and to keep your eye on the ball,” Peavy said. “What’s remarkable is that even with that huge stride, his head stayed relatively level.”

Striding forward, Mantle threw all the accumulated force against his locked front leg, which is typical of left-handed power hitters. Those forces are considerable. By way of comparison, Peavy collected force plate data on a college player approximately Mantle’s height and weight. His swing generated a force 2½ to 3 times his body weight.

As he shifted his weight from back to front, his hips and shoulders shifted up and down “like a teeter-totter,” Osteen says. “I keep centering on the hip bar. Swinging from down to up creates a 45-degree angle in the hips from back to the front. On the left side, his back hip is much, much lower than on the right—I’d say 1 to 2 inches. That shoulder bar is even lower.”

That posture made him a formidable low-ball hitter. “You don’t want to throw the ball down in that power zone,” Osteen said. “Usually you try to keep the fastball at belt-buckle height. If you go down, you prefer it to be near the dirt. If it is a breaking ball, it

has

to be in the dirt.”

As he moved forward, he lifted his back foot was as much as 3 to 6 inches off the ground, prima facie evidence of a complete transfer of weight onto his front side. To the trained eye of a batting coach, the height of his toe isn’t as significant as how far his back foot traveled. “My God, when you’re striding 24 inches or more, you gotta bring that back leg with you,” Peavy said, and Mantle did, sometimes as much as 1½ feet. In some pictures, you can see a small cloud of dust kicked up by his cleat as his front hip pulled his backside forward.

His right-handed stride was more compact, perhaps 12 to 15 inches, Peavy says, typical of a modern power hitter. It was also kinder to his knee; he didn’t extend it fully, or lock it in place. “His back foot was off the ground 1 to 4 inches,” Peavy said, evidence of a less vociferous stride. “And it didn’t move forward much, if at all.”

His shoulders remained on an even keel throught this swing, an indication of where the pitch was—waist high. “He probably doesn’t swing at a lot of pitches down,” Osteen said. “He would prefer to wait you out and make a mistake around the waist or higher.”

Because his posture was upright, his head remained virtually stationary until after he hit the ball. “That’s one of the secrets of hitting,” Osteen said. “He had a quiet body and a quiet head.”

The willful, learned aggression that made him such a fierce left-handed presence also contributed to his undoing. Watching film taken during Mantle’s brief tenure with the Kansas City Blues in the summer of 1951, Peavy noted that Mantle’s right front knee was slightly hyperextended when he made contact with the ball. That is not unusual for left-handed power hitters. But the torque on Mantle’s knee was accentuated by the toe-in position of his lead foot, according to Amy Engelsman, P.T., a sports-certified specialist in Washington, D.C. who has treated many professional athletes. Worse, as he followed through on his swing, his right ankle turned outward, rolling over as you might in a bad sprain. All the weight was forced onto the outside of his foot. “There was no way he could stay completely balanced with his foot planted,” Peavy said. “He would have ripped his knee apart.”

Two months after that footage was taken, that knee was torn apart during the 1951 World Series, compromising ligaments and tearing insulating cartilage. “With an intact anterior cruciate ligament, your knee can

remain stable even with that kind of swing,” Engelsman said. “Without the ACL the shearing forces on the knee would have contributed to the breakdown of the damaged cartilage.”

Over time, as the joint became more arthritic and less stable, “his swing would have atrophied,” Peavy said, and his knee would have buckled as it did so often and so visibly late in his career.

Osteen saw that happen to other injured left-handed power hitters. “That knee won’t let you spin the hips to bring your hands to the down and in position,” he said. “Then they become vulnerable to being jammed. That’s what happened to Mantle.”