The Last Living Slut (7 page)

Read The Last Living Slut Online

Authors: Roxana Shirazi

“We’ve gone from bad to worse,” I’d hear my mum tell my grandmother in a somber whisper, as if there might be covert spies for Khomeini among our neighbors. “God, when is our country going to be free?”

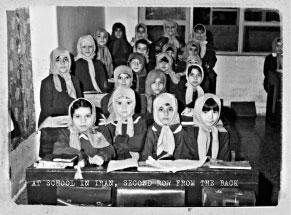

Every morning at school, we lined up to display our fingernails to the head teachers, then bowed our heads and recited from the Qur’an in rhythmic unison. I found the prayer hypnotic and soothing. In the afternoons, I devoured my class work: math, science, and literature. The hard work paid off and I achieved straight As in every subject at school. The head teacher gave me flowers and my family fawned over me. “She has a unique beauty, and so intelligent, too,” my aunts would nudge my mother, gathering around to observe me like some rare plant. “She will definitely find a nice husband.”

I spent my free time in the alley, reading fairy tales and talking about boys with Soraya and Zari, my dearest friends in the world, who were like sisters to me. Together, we ruled the neighborhood. The other girls followed us, hanging on our every word. When they gushed, “You are a princess, like Cinderella,” my heart swelled full of love.

My new dad ditched his job as a cab driver and started a construction company, where he made much more money. Soon he took us to gorgeous uptown restaurants and bought me prettier clothes, which I enjoyed showing off.

I lusted after the boys who lived nearby—many of them streetwise, bad-boy types. I would strut down the street in my platform shoes, ambling around the corner where they hung out. Though I acted innocent and unaware of their gaze, I’d slide my head scarf back just so, revealing my pearl hair clips. And I’d unbutton my montoe slightly, sauntering right past the Pasdar stationed at the end of our street. My friends watched from the windows, giggling nervously at what was either my extreme bravery or stupidity.

My uncles grew increasingly frantic. The new Islamic regime was torturing and executing everyone caught criticizing the government in any way, along with anyone thought to harbor left-wing, anti-government views—the pro-monarchists, the liberals, the intellectuals, anyone who did not actively follow Islamic practices. Even teenage girls who resisted religious teaching at school were considered potential threats and imprisoned, tortured, and executed.

My family began burning left-wing literature in the house. Late at night, I’d sit with my parents and relatives as they drove to the edge of town to dump boxes and boxes full of dangerous papers in the secret black waters of the river. All the freedom fighting, the turmoil, the blood spilled to liberate us from the Shah’s dictatorship had only put us in a far more dire situation.

I Decided that I would try it with Two Boys, While in The Next Room War Songs Blared out from The Television.

M

y baby brother came along, chubby and dribbly, smiling a fat, toothless smile, on March 21, 1980. It was

Eideh Norooz

, the non-Islamic holiday that also marks the first day of spring and the New Year.

My stepfather rushed my mum to the hospital that day, leaving my grandmother, aunts, uncles, and me waiting for news. We sat around the

Haft Sin

table. Haft Sin, meaning seven Ss, refers to seven specific items beginning with the letter S in the Persian alphabet that must be placed on the table during Norooz. Each of the items symbolizes a different concept:

Sib

are apples symbolizing beauty,

senjed

is a dried fruit that symbolizes love,

sir

is garlic,

sabzeh

are wheat sprouts grown in a dish for the occasion,

somagh

is the cooking spice sumac,

sonbol

is the plant hyacinth, and

sekkeh

are coins symbolizing prosperity. Decorated eggs, a mirror, lit candles, and a goldfish also crowned the table.

In all the excitement surrounding the new baby, I forgot about the holiday gifts. I didn’t need any—my brother, that chubby little bundle of sunshine, was the best present in the world. That day, I wrote my new brother a letter telling him how much I loved him and that he was a natural-born beauty.

Six months later, war erupted between Iran and Iraq. Air-raid sirens began shrieking like caged beasts. The sirens screamed every day. They scared the shit out of me, making me think we were about to get bombed, slaughtered.

All day, every day, military songs blared from our TV. The government wanted each male citizen—even old men and teenage boys—to fight the Iraqis. They promised martyrdom, an automatic free pass to heaven. We could not turn away from the broadcast images of families waving good-bye to their sons. A few boys from our street left to fight Saddam. Their mothers wailed hysterically from the pain of the sacrifice their sons were making for Islam.

During this time I took frequent walks to my grandmother’s house, either after school or in the early evening, as the grieving dusk prayers boomed from the mosque’s loudspeakers. Doom and fear hung thick and stagnant in the air as more and more men were called to war. The dusty nights were bleak, the street vendors increasingly desperate.

Walking beyond the main street, with cars violently whizzing past, angry drivers screaming, and armed men in Jeeps looking at me funny I’d smell the aromas of cooked liver and freshly baked nooneh sangak. I passed the pastry shops with strawberry-glazed cream puffs and crumbly confections in the windows. Dolls with spider-leg eyelashes and exotic animal toys with drum sets slept in shops, closed for the night. Teenage boys, likely just days away from war’s brutality, pedaled bicycles along the sooty streets. The rich little girls held tight to their daddies’ hands by florist shops crammed full of funeral wreaths and bridal bouquets.

I would run to my grandmother’s house, pressing my head against her heaving bosom and big belly. I breathed deeply, inhaling her love. It was a small, safe place in the world. I no longer missed my real father: My new dad taught me how to ride a bike, holding on to the back and running behind and letting go only when I told him to. He taught me how to dine like a lady, but he also slapped me when I was bad.

One day, as I played with my bike in the yard with my mum and dad, my first daddy appeared, tall and slim with his film–star–tinted glasses and lovely lips. Avoiding eye contact with me, he walked right up to my new father. His whisper was dry and straight to the point: “I don’t want to have any more responsibility for her. I won’t be seeing her again. You can officially be the dad.” Then he turned and left as hurriedly as he’d come. I looked down at my bike, at the Pink Panther stickers on the plastic between the handlebars, at the glitter-sprinkled dancing dolls in the basket, and I felt like nothing. I knew that I was damaged goods.

It was around this time that my stepfather first beat me. I remember standing in the shower where a bright, fresh pool of blood gushed from my nose and stained the water. My face was all puffed up and ugly and I fucking hated looking ugly. I thought I deserved it because I’d been a smart-ass, and getting smacked in the face was part of the deal for a cheeky kid who answered back. No one stood up for me, not even my mother; after all, he was her husband now, and Iranians don’t discuss such things. It brings shame on the family.

By now my brother was a toddler. He would wiggle his wobbly jelly bottom whenever a war anthem played on TV, which seemed to be every five minutes. There was practically a funeral a day in the neighborhood. Shrines dedicated to the local martyrs sprouted up all over town; gorgeous colored lights bathed the dead soldiers’ photos. At night, while the lizards slithered near the lamps in our yard, bombs destroyed the smaller southern cities, and even Tehran endured the occasional blast. When the sirens sounded, we swarmed into our block’s underground parking garage for shelter.

Despite the terror, I thought life was still grand. I loved my friends and was the top student at school. I studied the Qur’an and devoured my textbooks, hungrily lapping up lessons in science and history. Religion was different, however, because religion made me feel peaceful and at one with God—especially since it was everywhere: on TV, blaring from the mosque’s loudspeakers, and at school, where heaven and hell were constantly drummed into our brains. If I was a good girl and said my prayers every day and loved God, I would go to heaven. If I was a naughty girl, flaunting my sexuality and flirting with boys, I was destined for hell.

God, I tried to be virtuous and pure. I tried so hard. But I was tainted by my dirty thoughts. I just couldn’t help myself. They became real every day when I played with my boy cousins and neighbors in private, hidden from the eyes of adults. I would get naked and rub my eight-year-old chest against my cousin’s bare torso. Then in the afternoon I’d find my nine-year-old neighbor, a boy named Hamid, and get him to play doctor-and-patient with me. I would undress, climb in bed, make him examine me down there, and lie silently, letting him explore. I would bring Soraya and Zari to my room and ask them to look at my body and touch my private parts, relishing every sigh, every touch, every finger. In the midst of it, I could still feel God looking down upon me with loathing.

One night I decided to try it with two boys. I had exploding feelings in my tummy but no logic in my head. While my parents and family friends gathered in the living room to talk politics and war songs blared from the TV calling everyone to sacrifice their sons, I brought my younger boy cousin, Kian, to my room and asked Hamid to join us.

“We’re playing servants and housekeepers,” Hamid told Kian, somehow reading my mind. “She’s going to lie down on the bed like she’s asleep. You have to pretend you are a servant and do as you are told.”

Hamid’s imagination is just like mine, I thought gleefully.

I lay down on the bed and closed my eyes. Hamid ordered Kian to touch me. I pretended to doze like Sleeping Beauty. Hamid was harsh with Kian, commanding him to kiss my feet and thighs. I felt like I was floating. I felt like a queen. The game made my tummy tumble with frenzy. I worried that we were too cruel to my cousin, who, bewildered and meek, went along with whatever we told him to do.

I knew I had power—a real power—over boys. And I exercised it whenever the fancy took me. One afternoon, I finished school early after a grueling day of listening to sermons about heaven and hell and where we might end up if we got on the wrong side of God. Clutching my books, with thoughts of fires and snakes running through my mind, I walked home. There I found our neighbor’s eight-year-old brother hanging around out in front. Knowing no one was home, I took the wide-eyed boy into my room and forced him to kiss me. I fondled under my panties and straddled him as I removed my

hejab

(head scarf). He panted hard, fingered me, and blushed crimson. I was in ecstasy, a pack of wild wolves in my belly. There. Now I was definitely going to hell.

M

y family made frequent trips to

Shomal

(the north of Iran), where crystal waters and powder-soft sand welcomed us. On the drive there, we passed majestic blue mountains. The Persian wilderness, the forests, the lakes, and the ancient hills looked like a fairy-tale painting. There were small cafés and restaurants tucked into the belly of the mountain. We rested on their sofas and beds, atop intricately patterned cushions, while being served little plates of feta cheese, Persian dips with freshly baked bread, and hot tea in dainty glasses. Sometimes we shared our hotel room with a harmless snake; the damp weather invited many wiggling creatures.

By 1982, the beach had been segregated: a makeshift wall divided the men from the women, despite the fact that all females still had to adhere to the Islamic dress code, even in the sea. One afternoon, as I scampered around the beach, a male Pasdar screamed obscenities at me for not covering my arms and legs. I felt like a criminal.

Another day, as we were driving home from Shomal, I gently held my new baby sister—less than a year old—in my arms, wondering how long it would be until she had to cover her body, too. Suddenly we were pulled over by the Pasdar. They screamed at my parents to get out of the car. We had no idea what we could have done wrong.