The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (10 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

Kirchner was a skinny kid of average height, with black hair slicked back from a broad forehead. He had a prominent, aquiline nose and powerful thighs and calves. In the morning, he and some of his buddies had started Indian leg wrestling to break the monotony. The teenage Korean boy watched them for a while and finally got up the gumption to challenge Kirchner to a match. Kirchner had been taught to raise his leg three times to signal the start of the action, but the boy did not know any such formality. As Kirchner was raising his leg for the first time the boy jumped him, caught him off balance, and nearly broke his back.

Everyone got a big laugh out of it, including Kirchner, who demanded a rematch. This time, prepared, Kirchner lifted the boy clear in the air and threw him right through the door-where he landed on top of Lieutenant Peterson.

Peterson came rushing into the hootch with his sidearm drawn, and it took the Marines a moment to explain that they were only playing. Two nights later, out on patrol east of Hagaru-ri, Kirchner and his squad were ambushed. During the firefight he recognized the same boy, who was about to heave a grenade when Kirchner shot him dead. He hadn't told anyone about the incident.

Now he set down his spade and gazed up at Lieutenant Peterson. "I don't know, sir," he said. There was a hint of sadness to his voice. "I don't think we'll be seeing that kid again."

6

Howard Koone and Dick Bonelli, having dug no more than twelve inches into the rocky, frozen ground, gave up. They placed their backpacks on the forward lip of the shallow depression to use as parapets for their rifles. They also piled more snow around the edges of their half-assed foxhole, fully aware that as hard-packed as it might be, it would not stop a bullet. Before sunset Bonelli had been able to look down from his elevated position and glimpse, between cloud banks, the black-ice contours of the southern arm of the Chosin Reservoir as it snaked behind the crevassed inclines of Toktong-san. Now the snow clouds had dispersed, the stars had not yet risen, and in the clear night sky Bonelli could see orange flashes of artillery fire up near the reservoir.

Their fingers numb from the cold, Bonelli and Koone tore scraps of paper from their C-ration boxes. Before being shipped overseas Bonelli had participated in cold-weather maneuvers in Labrador, Canada. That was Tahiti compared with this. He removed a mitten and lit a waterproof match, but the wind blew it out. He tried to pull another match from the folder, but his bare fingers were already so frozen and stiff he couldn't detach it from the pack. In the bitter cold even the simplest task became as difficult as boning a marlin.

He held out the solitary match, still attached to its folder. Koone whipped off a glove and got it lit. He put it to the paper while they both blocked the wind with their bodies. They sheltered the small flame, and across the crest of Fox Hill and up and down its flanks more fires began to flicker. "Eat everything," Koone said. "You don't know if we're even going to be here tomorrow."

One of the new boots asked Bonelli about the Uijongbu campaign, in which Bonelli had fought after the landing at Inchon six weeks earlier. Bonelli snorted.

"Like a Marx Brothers movie," he said. "One time I'm out on a listening post all by myself, cleaning my rifle, when out of nowhere this North Korean soldier walks right up to me. `Who the hell are you?' I said. 'And what the hell you doing here?' 'Strolling,' the guy tells me. Perfect English. Strolling! So I whipped my bayonet around and caught him in the thigh. He half-runs and half-gimps away. But I chase him down. Dove and caught him. Was about to give it to him good when a South Korean patrol comes by and nails him. Only time I ever saw a ROK do anything worthwhile."

He continued. "See, what the gooks did, they had these big mortars, and they had good maps. They would drop a shell in your lap before you could blink. And this guy was their spotter."

By now the two boots were mesmerized, and Bonelli couldn't help himself. "Ever tell you about the time I robbed the Korean bank?" he said.

It made for a good bedtime story for "the kids," Bonelli thought. He began to reminisce about how, during the Uijongbu campaign, his patrol had run across a bombed-out bank and blown the safe with grenades. They thought they were rich and would come back and buy the country after the war was over.

Bonelli looked at Koone. For once the Indian smiled. "Thousanddollar bills," Bonelli said. He drew his gloved hands apart. "Stacks of them. Filled a duffel bag."

Stan Golembieski leaned in. "What did you do with all the cash?"

Bonelli could feel the anticipation build as he made them wait for the kicker. Then he said, "Used 'em to make a fire the next morning. Brewed the best pot of coffee I ever tasted with that money."

A spectral winter fog stole up the valleys of the Toktong Pass at 6:30 p.m. as the Third Platoon commander Lieutenant McCarthy and his platoon sergeant, John Audas, inspected their dug-in positions along the crest of the hill. They informed their riflemen that earlier in the day the Seventh and Fifth Regiments at Yudam-ni had made contact with Chinese units. When Bonelli heard this he decided to move the knapsack he had placed on the parapet of his hole so it sat between him and the worrisome thicket. It had frozen solid to the snow.

At 7 p.m. a bonfire was started at the base of the hill near the company command post tent. The mortarmen, the heavy machine gun crews, and the headquarters unit moved close. Because of the rises, depressions, ridgeline contours, and fir trees, the flames could not be seen by Marines at the top of the hill. Stories around the fire tended, as usual, toward past conquests in love and war, some of them true. There is no sincerity like that of a soldier telling a lie. Soon the conversation came to be dominated by one question: Think we'll be home for Christmas?

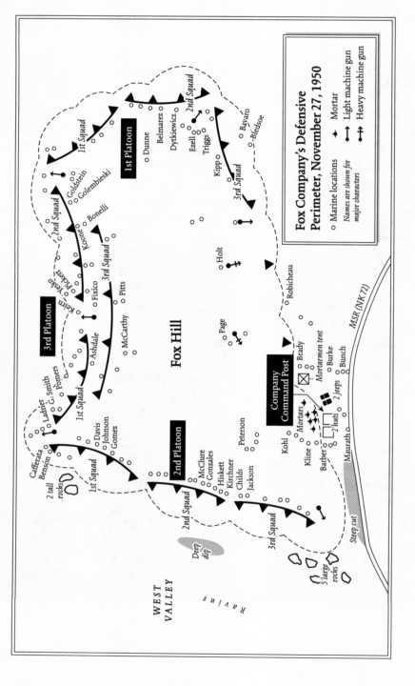

At 9 p.m. Captain Barber's three rifle platoon leaders informed him by field phone that they had secured their positions for the night. Fox Company was strung over the hill like a pearl necklace. Barber ordered all fires extinguished, and the men were given passwords. They were placed on two-hour, fifty-fifty watches: one man would sleep while the other stood sentry. Ten minutes later several Marines near the road heard the last convoy of trucks from Yudam-ni coughing soot as they rolled south on the MSR en route to Hagaru-ri.

A four-day-old moon, nearly full and glowing as white as a spotlight, rose at 9:30 p.m. from behind the South Hill across the MSR. Thousands of stars lit up the sky. The temperature hovered near minus-thirty degrees Fahrenheit.

Just before midnight, Captain Barber radioed Lieutenant Colonel Randolph Lockwood in Hagaru-ri. He informed his superior officer that the 234 Marines, twelve corpsmen, and one civilian interpreter of Fox Company, Second Battalion, Seventh Marines, were ready, able, and effective.

THE ATTACK

DAY TWO

NOVEMBER 28, 1950 TWELVE MIDNIGHT TO 6 A.M.

1

Lieutenant Bob McCarthy had been only mildly upset about losing his argument with Sergeant John Henry about the positioning of the heavy machine guns. Now he was livid. Less than an hour earlier he'd reconnoitered the Third Platoon's perimeter across the hilltop. Half the men had failed to challenge his approach. He had been forced to "chunk" a few helmets with his rifle butt. He didn't care how cold and tired the men were. Anything to make them mad, even if they're mad at me. Angry men are alert men.

Now, at 1:15 a.m., he was back in his command post, or CP, reaming out his squad leaders. McCarthy had established the Third Rifle Platoon's CP in an old enemy bunker that his staff sergeant, Clyde Pitts, had discovered about thirty yards below the crest of the hill. The dugout wasn't much more than a pit, and its roof planks were rotting, but at least they would keep out most of the snow, which had again begun falling lightly. Despite his ill humor, the lieutenant thanked God for Pitts. He was a Marine lifer, a veteran of numerous Pacific campaigns during World War II, and a worldclass scrounger. Like Captain Barber, McCarthy was new to Fox Company, having arrived in Koto-ri only a day after the new commanding officer. He'd been the skipper of a weapons company in the States, and he knew guns.

One morning after the outfit had reached Hagaru-ri, McCarthy had ordered a snap weapons inspection. Of the nine fire teams in his platoon, only one had a working BAR. The remainder were so old and sluggish, with recoil springs that failed to react in the cold, that they were practically useless. He immediately summoned Pitts.

"Staff Sergeant, I don't know where they're coming from, or how you're going to do it, but I want eight working BARs here by sundown. Do you understand, Sergeant?"

Pitts nodded, spit a thick wad of tobacco juice in the snow at McCarthy's feet, and responded-well, responded with something that appeared to be an affirmative. McCarthy was barely able to understand the sergeant's words through his cotton-thick Alabama drawl. But he came through. That night McCarthy distributed eight new BARs to his fire teams. He never asked Pitts where they had come from.

Now Pitts was perhaps the most red-faced of all the noncoms seated in a semicircle around McCarthy as he voiced his displeasure over the company's lack of alertness before sending them out to square away the problem. Fifteen minutes later, McCarthy pulled another surprise inspection. Password challenges rang out loud and clear in the thin, crisp air.