The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (5 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

Upon reaching the switchback where the MSR looped east to west at the apex of the pass, Barber and Lockwood dismounted before a steep, broad eminence on the north side of the road and began climbing in the shadow of Toktong-san. They were at 4,850 feet when they reached the eighty-yard-wide crest of the promontory, a shoulder of the big mountain. The effect of being cut off from the sea by mountains to the west, east, and southeast had extraordinary consequences. The raw, wet wind screaming out of the Arctic and across the Manchurian plain, and then funneling through the pass, was the fiercest either man had ever encountered. The area around the Chosin Reservoir was said to be the coldest place in Korea, and the fallow terrain was the only ground in the country where rice could not be grown. The local peasants knew to expect an average of sixteen to twenty weeks each winter when the average temperature never rose above zero degrees Fahrenheit, and Barber could not help wondering how drastically this cold would reduce his company's combat efficiency.

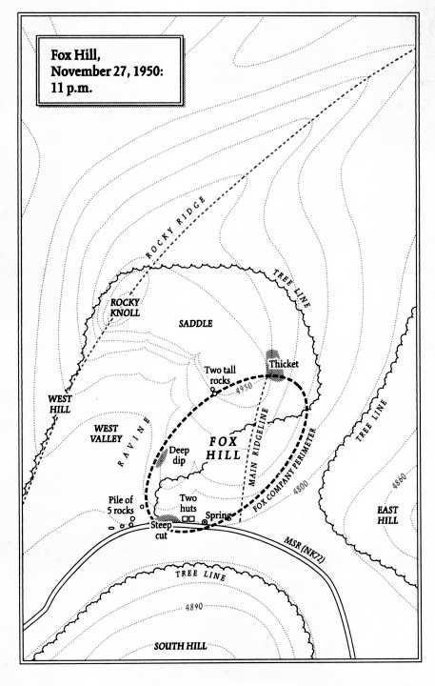

The hill they stood on loomed above two narrow valleys and occupied an area about the size of three football fields. At the top of the hill, on the northwest quadrant, the ground extended to form a narrow saddle-seventy-five yards wide and humped like a whale's back. This land bridge, which ran three hundred yards, fell away sharply on both sides and ended at a large rocky knoll. Above and beyond the rocky knoll a string of higher, serrated rocky ridges ran another one-third mile like a gleaming white staircase up the looming bulk of Toktong-san.

Except for the narrow saddle, the hill was well separated from the other heights in all directions by slender, snow-covered valleys. The basins to the east and west stretched a bit over two hundred yards across, with the western depression bisected by a deep ravine running lengthwise up to the edge of the saddle. The wider southern vale-level bottom ground with brown tufts of alpine grass dotting the snow like miniature haystacks-ran nearly three hundred yards. These valleys separated the hill from three similar, treeskirted knolls to the east, west, and south.

Delineating the base of the hill, adjacent to the road, was a sheer cut bank, ten feet high by forty feet long, where the MSR had been chiseled out of the heights eighteen years earlier during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Past this steep wall, neat rows of fir trees, four to five inches thick at the trunk and perhaps forty feet tall, climbed two-thirds of the way up the slope. These immature dwarf pines, also planted by the Japanese as part of an emergency reforestation program, were spaced eight to ten feet apart. Above the tree line the crest of the hill sported small patches of gnarled brush that pushed through the hard-packed, knee-deep snow. The undulating hilltop was also broken by countless rocks and colossal boulders. Two of the largest boulders-a pair of tall, flat-faced rocks, eight feet high by six feet across-dominated the northwest corner of the peak at the beginning of the saddle. They resembled giant dominoes.

The hill's main, central ridgeline rose to 225 yards above the road at its northeast corner, and dipped to 175 yards high at the northwest peak, where the saddle began. A secondary, catty-corner ridgeline bisected the hill from the lower, southwest corner and petered out at the tree line. The entire hill was pocked and pleated with depressions, erosion folds, and a few old bivouac bunkers and foxholes that had been rocketed and napalmed by the Americans as Litzenberg had ascended the pass on his march to Yudam-ni. A shallow gully, twenty yards wide, ran straight up the middle of the hill from the road to just beyond the trees. In the lower, southeast corner, below the fir tree plantation, a freshwater spring flowed out of the mountains despite the freezing temperature.

Near the spring, two abandoned huts had been built several yards back from the road. These structures were about ten feet high, with dirt floors, low-pitched roofs, and doorless openings at either end. The larger hut, which ran parallel to the MSR, was perhaps twelve by twenty feet and was divided into two sections. It looked as if it had been a subsistence farmhouse-half of it seemed to be a kitchen. The slightly smaller hut, sitting at a right angle about ten yards up the hill behind the main house, retained a strong odor of farm animals and had a large grain storage bin at its south end, closest to the main building.

As Barber and Lockwood climbed back down to their Jeep, the new commanding officer of Fox Company was already conceptualizing his defensive perimeter. His Marines, Barber told Lockwood, would defend Toktong Pass from this hill. He would align his men up the gentler eastern grade, across the crest, and down the steep western slope in the general shape of an inverted horseshoe, the "reverse U" position taught at Quantico. The road would "close" the two piers of the horseshoe, with the breadth of the oval perhaps 155 yards wide from east to west.

After Lockwood accepted his plan, Barber asked to remain at the pass while Lockwood returned to Hagaru-ri. Lockwood reluctantly agreed and told him to expect the arrival of his company within the hour.

Back in the village, however, Lockwood could find no vehicles to transport Fox Company up the MSR. At 2 p.m. word passed among the men that they would be hiking the seven miles up the icy, muddy, glorified goat trail. One Marine noted in his journal, "Now we gripe openly and vociferously."

The footsore Marines of Fox Company were not happy to be lugging more than sixty pounds each of weapons, ammo, and gear up the road. In addition to the standard-issue Garland MI-an eight-shot, clip-fed semiautomatic rifle that weighed about ten pounds-they carried carbines, .45-caliber sidearms, light machine guns, mortar barrel tubes and plates, bazookas, entrenching tools, boxes and bandoliers of ammunition, cartons of C rations, satchels of grenades, heavy down sleeping bags, command post and medical tents, medical supplies, a radio and field phones, half-tent covers, and personal items such as books, extra socks, souvenirs, and a bathroom kit. Some had .38-caliber pistols, gifts sent from home, in shoulder holsters under their armpits.

They were also swathed in bulky layers of winter clothing. Each man wore a pair of "windproof " dungarees over a pair of puke-green wool trousers and cotton long johns; a four-tiered upper-body layer of cotton undershirt, wool top shirt, dungaree jacket, and Navyissue, calf-length, alpaca-lined hooded parka; a wool cap with earflaps and visor beneath a helmet; wool shoe pads and socks worn beneath cleated, rubberized winter boots, or shoepacs; and heavyduty gloves covering leather or canvas mittens. Some men had cut the trigger finger off their gloves.

This late in the afternoon, no one was confident of reaching Toktong Pass before dark, but luck struck when the company's forward artillery observer announced that he had scrounged transport from the commanding officer of How Company, the Second Battalion's 105-mm howitzer unit based at Hagaru-ri. The "arty boys" had agreed to lend Fox the nine trucks they used to lug their big guns.

"Bring them back with the tanks full," one of the artillerymen joked, and at 2:30 p.m. the company was ordered to saddle up. As men climbed onto the open flatbeds of the six-by-sixes and squeezed into the seats of the company Jeep-some Marines riding on the hoods-more than a few freezing men wondered where their new commanding officer was.

4

If Fox Company was suspicious of its new spit-and-polish CO, he too was leery of them. Following the landings at Inchon, the company had taken heavy casualties during the Uijongbu campaign north of Seoul. Then, on the push north to the Yalu as winter set in, frostbite had become more effective at thinning the outfit than the random roadside ambushes. By the time Barber assumed command at Koto-ri nearly half the unit consisted of fresh "boots" and most of its officers were as new to Korea as Barber was.

The company was nowhere near its full strength, and one day on the road near Koto-ri Barber watched aghast as an entire squad failed to take out three fleeing North Korean soldiers no more than two hundred yards away. On Iwo, this would have been a job for one Marine. Barber's defining character trait may have been his rigorous self-discipline, and he expected no less from the men under his command. Thereafter he instituted a routine of daily rifle practice on makeshift ranges, using cans cadged from the mess tents as targets.

This did not sit well with weary, frozen Marines who could see warming campfires and smell coffee roasting while they lay prone in the snow firing at bacon tins. Oddly, however, despite the punishment no one considered Barber a mean-spirited leader. Unlike many Marine commanders, he took pains to explain the reasons for every reprimand he issued. And in this case the regimen worked. Before long each man in the outfit had improved his marksmanship impressively.

Similarly, during skirmishes along the trek to Hagaru-ri, Barber found hands-on opportunities to teach his new line replacements how to call in close air support, register artillery rounds, and fire the mortars at night. (Sometimes, to his men's perplexed amazement, he would simultaneously break out in a full-throated rendition of the Marine Corps hymn.) All in all, Barber felt that by the time Fox Company set off for Toktong Pass his "training on the run" had not only improved his unit's fighting skills but brought the men together as a cohesive team. They would need to be.

Barber had studied Sun-tzu and was also familiar with the military writings of Mao Tse-tung, who had been strongly influenced by Sun-tzu's ancient but still practical strategies during the recent Chinese civil war. "The reason we have always advanced a policy of luring the enemy to penetrate deeply," Mao had written in On Protracted War, "is that it is the most effective tactic against a strong opponent."

Now, alone on a vital pass, Barber took another look at North Korea's unforgiving mountains. Who was out there? And in what strength? The Chinese had been fighting in these hills for millennia, and Barber again considered Sun-tzu, who had set down his ideas in the fourth century BC. If Mao was still following those precepts, the odds were that the First Marine Division was being lured into a trap.

And, Barber noted, his company, his first command in Korea, was right in the thick of it.

At 3 p.m. the convoy carrying most of the three rifle platoons and the headquarters staff of Fox Company left Hagaru-ri and began the climb up to Toktong Pass. Even with the nine borrowed trucks, however, there were not enough vehicles to transport the entire outfit, its equipment, and the adjunct details now assigned to it. The company had been reinforced by an 81-mm mortar section consisting of two tubes each manned by ten Marines, as well as an additional eighteen Marines from the Second Battalion's heavy weapons section who toted two water-cooled Browning. 3 0-caliber heavy machine guns. About two dozen men from the First Rifle Platoon had to be left behind until the trucks could return for them. As drivers gunned their engines, more than a few men slept where they dropped in the flatbeds.

The MSR was wide enough to permit the passage of only a single vehicle, and the convoy's progress was delayed when it found itself in a trace to a column of slow-moving tractors towing a battery of 155-mm howitzers to Yudam-ni. Not until 5 p.m. did Captain Barber-by now rejoined by Lieutenant Colonel Lockwood, who had transported a cameraman to the hill to record the company's arrival-see Fox's lead Jeep coming up the winding road. The Jeep, its trailer laden with gear, pulled over next to the two abandoned huts. Barber directed the convoy onward, until the entire line of vehicles was adjacent to the base of the hill. Upon orders to dismount, several Marines had to be shaken awake, including Private First Class Warren McClure, the BAR man of the First Fire Team, Second Squad, Second Platoon.

McClure had dreamed of carrying a BAR since high school, when his guidance counselor, a Marine veteran who had earned a Bronze Star on Iwo Jima, regaled him with stories about fighting the Japanese. McClure, who described himself as a hillbilly, had grown up in a small town in central Missouri near the Lake of the Ozarks. He and his friends had devoured war movies of the 1940s and reenacted famous battles of World War II almost daily in their backyard fields. When his family moved to Kansas City, he enlisted in his school's Marine reserve program and spent summers and weekends with an artillery battalion learning to operate 105-mm howitzers.

In the summer of 1950 McClure was preparing to leave for boot camp. When war broke out in Korea, he was instead ordered onto a troop train bound for San Diego. He assumed he would be assigned to an artillery outfit. Instead, to his surprise and delight, when he arrived at Camp Pendleton he was drafted into a Marine rifle company.

"We went out and threw three grenades and fired twenty rounds from a BAR, and that was my training," he would later explain to his assistant in Fox Company, Private First Class Roger Gonzales. "Then they asked for a volunteer to be the BAR man."

McClure jumped at the opportunity. The air-cooled, gasoperated BAR-the Browning automatic rifle, steady, fast-firing, and accurate to five hundred yards-was considered the finest oneman weapon in the infantry, the ultimate in battlefield efficiency. It weighed twenty pounds complete with bipod and twenty-round magazine, and it was the basis for a Marine fire team. The model for this four-man team had been developed ten years earlier at Quantico, and once again the Corps seemed to have borrowed from the Society of Jesus, for the concept was a variation of the Jesuit tenet of freedom within discipline. Its beauty lay in its simplicity.