The Life of the Mind (31 page)

Read The Life of the Mind Online

Authors: Hannah Arendt

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Philosophy, #Psychology, #Politics

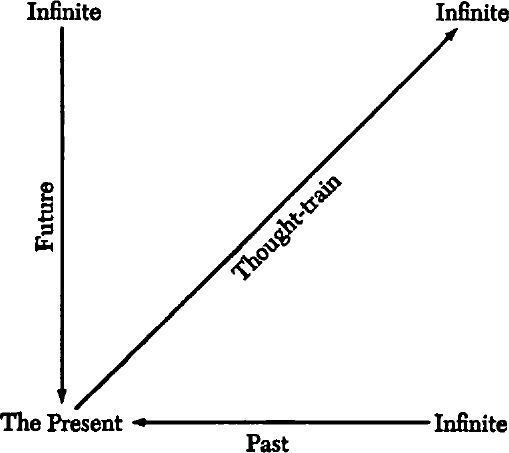

Without "him," there would be no difference between past and future, but oply everlasting change. Or else these forces would clash head on and annihilate each other. But thanks to the insertion of a fighting presence, they meet at an angle, and the correct image would then have to be what the physicists call a parallelogram of forces. The advantage of this image is that the region of thought would no longer have to be situated beyond and above the world and human time; the fighter would no longer have to jump out of the fighting line in order to find the quiet and the stillness necessary for thinking. "He" would recognize that "his" fighting has not been in vain, since the battleground itself supplies the region where "he" can rest when "he" is exhausted. In other words, the location of the thinking ego in time would be the in-between of past and future, the present, this mysterious and slippery now, a mere gap in time, toward which nevertheless the more solid tenses of past and future are directed insofar as they denote that which

is

no more and that which

is

not yet. That they

are

at all, they obviously owe to man, who has inserted himself between them and established his presence there. Let me briefly follow the implications of the corrected image.

Ideally, the action of the two forces that form our parallelogram should result in a third force, the resultant diagonal whose origin would be the point at which the forces meet and upon which they act. The diagonal would remain on the same plane and not jump out of the dimension of the forces of time, but it would in one important respect differ from the forces whose result it is. The two antagonistic forces of past and future are both indefinite as to their origin; seen from the viewpoint of the present in the middle, the one comes from an infinite past and the other from an infinite future. But though they have no known beginning, they have a terminal ending, the point at which they meet and clash, which is the present. The diagonal force, on the contrary, has a definite origin, its starting-point being the clash of the two other forces, but it would be infinite with respect to its ending since it has resulted from the concerted action of two forces whose origin is infinity. This diagonal force, whose origin is known, whose direction is determined by past and future, but which exerts its force toward an undetermined end as though it could reach out into infinity, seems to me a perfect metaphor for the activity of thought.

If Kafka's "he" were able to walk along this diagonal, in perfect equidistance from the pressing forces of past and future, he would not, as the parable demands, have jumped out of the fighting line to be above and beyond the melee. For this diagonal, though pointing to some infinity, is limited, enclosed, as it were, by the forces of past and future, and thus protected against the void; it remains bound to and is rooted in the presentâan entirely human present though it is fully actualized only in the thinking process and lasts no longer than this process lasts. It is the quiet of the Now in the time-pressed, time-tossed existence of man; it is somehow, to change the metaphor, the quiet in the center of a storm which, though totally unlike the storm, still belongs to it. In this gap between past and future, we find our place in time when we think, that is, when we are sufficiently removed from past and future to be relied on to find out their meaning, to assume the position of "umpire," of arbiter and judge over the manifold, never-ending affairs of human existence in the world, never arriving at a final solution to their riddles but ready with ever-new answers to the question of what it may be all about.

Â

To avoid misunderstanding: the images I am using here to indicate, metaphorically and tentatively, the location of thought can be valid only within the realm of mental phenomena. Applied to historical or biographical time, these metaphors cannot possibly make sense; gaps in time do not occur there. Only insofar as he thinks, and that is insofar as he is

not,

according to Valéry, does manâa "He," as Kafka so rightly calls him, and not a "somebody"âin the full actuality of his concrete being, live in this gap between past and future, in this present which is timeless.

The gap, though we hear about it first as a

nunc stans,

the "standing now" in medieval philosophy, where it served, in the form of

nunc aetemitatis,

as model and metaphor for divine eternity,

13

is not a historical datum; it seems to be coeval with the existence of man on earth. Using a different metaphor, we call it the region of the spirit, but it is perhaps rather the path paved by thinking, the small inconspicuous track of non-time beaten by the activity of thought within the time-space given to natal and mortal men. Following that course, the thought-trains, remembrance and anticipation, save whatever they touch from the ruin of historical and biographical time. This small non-time space in the very heart of time, unlike the world and the culture into which we are born, cannot be inherited and handed down by tradition, although every great book of thought points to it somewhat crypticallyâas we found Heraclitus saying of the notoriously cryptic and unreliable Delphic oracle: "

oute le gei, oute kryptei alia'sémainei

" ("it does not say and it does not hide, it intimates").

Each new generation, every new human being, as he becomes conscious of being inserted between an infinite past and an infinite future, must discover and ploddingly pave anew the path of thought. And it is after all possible, and seems to me likely, that the strange survival of great works, their relative permanence throughout thousands of years, is due to their having been born in the small, inconspicuous track of non-time which their authors' thought had beaten between an infinite past and an infinite future by accepting past and future as directed, aimed, as it were, at themselvesâas

their

predecessors and successors,

their

past and

their

futureâthus establishing a present for themselves, a kind of timeless time in which men are able to create timeless works with which to transcend their own finiteness.

Â

This timelessness, to be sure, is not eternity; it springs, as it were, from the clash of past and future, whereas eternity is the boundary concept that is unthinkable because it indicates the collapse of all temporal dimensions. The temporal dimension of the

nunc stans

experienced in the activity of thinking gathers the absent tenses, the not-yet and the no-more, together into its own presence. This is Kant's "land of pure intellect"

(Land des reinen Verstandes),

"an island, enclosed by nature itself within unalterable limits," and "surrounded by a wide and stormy ocean," the sea of everyday life.

14

And though I do not think that this is "the land of truth," it certainly is the only domain where the whole of one's life and its meaningâwhich remains ungraspable for mortal men

(nemo ante mortem beatus esse did potest),

whose existence, in distinction from all other things which begin to

be

in the emphatic sense when they are completed, terminates when it

is

no moreâwhere this ungraspable whole can manifest itself as the sheer continuity of the I-am, an enduring presence in the midst of the world's ever-changing transitoriness. It is because of this experience of the thinking ego that the primacy of the present, the most transitory of the tenses in the world of appearances, became an almost dogmatic tenet of philosophical speculation.

Let me now at the end of these long reflections draw attention, not to my "method," not to my "criteria" or, worse, my "values"âall of which in such an enterprise are mercifully hidden from its author though they may be or, rather,

seem

to be quite manifest to reader and listenerâbut to what in my opinion is the basic assumption of this investigation. I have spoken about the metaphysical "fallacies," which, as we found, do contain important hints of what this curious out-of-order activity called thinking may be all about. In other words,I have clearly joined the ranks of those who for some time now have been attempting to dismantle metaphysics, and philosophy with all its categories, as we have known them from their beginning in Greece until today. Such dismantling is possible only on the assumption that the thread of tradition is broken and that we shall not be able to renew it. Historically speaking, what actually has broken down is the Roman trinity that for thousands of years united religion, authority, and tradition. The loss of this trinity does not destroy the past, and the dismantling process itself is not destructive; it only draws conclusions from a loss which is a fact and as such no longer a part of the "history of ideas" but of our political history, the history of our world.

What has been lost is the continuity of the past as it seemed to be handed down from generation to generation, developing in the process its own consistency. The dismantling process has its own technique, and I did not go into that here except peripherally. What you then are left with is still the past, but a

fragmented

past, which has lost its certainty of evaluation. About this, for brevity's sake, I shall quote a few lines which say it better and more densely than I could:

Â

Full fathom five thy father lies,

Of his bones are coral made,

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

The Tempest,

Act I, Scene 2

Â

It is with such fragments from the past, after their sea-change, that I have dealt here. That they could be used at all we owe to the timeless track that thinking beats into the world of space and time. If some of my listeners or readers should be tempted to try their luck at the technique of dismantling, let them be careful not to destroy the "rich and strange," the "coral" and the "pearls," which can probably be saved only as fragments.

Â

'O plunge your hands in water,

Plunge them in up to the wrist;

Stare, stare in the basin

And wonder what you've missed.

The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea-cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead...'

W. H. Auden

15

Â

Or to put the same in prose: "Some books are undeservedly forgotten, none are undeservedly remembered."

16

In the second volume of this work I shall deal with willing and judging, the two other mental activities. Looked at from the perspective of these time speculations, they concern matters that are absent either because they are not yet or because they are no more; but in contradistinction to the thinking activity, which deals with the invisibles in all experience and always tends to generalize, they always deal with particulars and in this respect are much closer to the world of appearances. If we wish to placate our common sense, so decisively offended by the need of reason to pursue its purposeless quest for meaning, it is tempting to justify this need solely on the grounds that thinking is an indispensable preparation for deciding what shall be and for evaluating what is no more. Since the past, being past, becomes subject to our judgment, judgment, in turn, would be a mere preparation for willing. This is undeniably the perspective, and, within limits, the legitimate perspective of man insofar as he is an acting being.

But this last attempt to defend the thinking activity against the reproach of being impractical and useless does not work. The decision the will arrives at can never be derived from the mechanics of desire or the deliberations of the intellect that may precede it. The will is either an organ of free spontaneity that interrupts all causal chains of motivation that would bind it or it is nothing but an illusion. In respect to desire, on one hand, and to reason, on the other, the will acts like "a kind of

coup d' état,

" as Bergson once said, and this implies, of course, that "free acts are exceptional": "although we are free whenever we are willing to get back into ourselves,

it seldom happens that we are willing'

(italics added).

17

In other words, it is impossible to deal with the willing activity without touching on the problem of freedom.

I propose to take the internal evidenceâin Bergson's terms, the "immediate datum of consciousness"âseriously and since I agree with many writers on this subject that this datum and all problems connected with it were unknown to Greek antiquity, I must accept that this faculty was "discovered," that we can date this discovery historically, and that we shall thereby find that it coincides with the discovery of human "inwardness" as a special region of our life. In brief, I shall analyze the faculty of the will in terms of its history.

I shall follow the experiences men have had with this paradoxical and self-contradictory faculty (every volition, since it speaks to itself in imperatives, produces its own counter-volition), starting from the Apostle Paul's early discovery of the will's impotenceâ"I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate"

18

âand going on to examine the testimony left us by the Middle Ages, beginning with Augustine's insight that what are "at war" are not the spirit and the flesh but the mind, as will, with itself, man's "inmost self' with itself. I shall then proceed to the modern age, which, with the rise of the notion of progress, exchanged the old philosophical primacy of the present over the other tenses against the primacy of the future, a force that in Hegel's words "the Now cannot resist," so that thinking is understood "as essentially the negation of something being directly present" ("in

der Tat ist das Denken wesentlich die Negation eines unmittelbar Vorhandenen

").

19

Or in the words of Schelling: "In the final and highest instance there is no other Being than Will"

20

âan attitude that found its final climactic and self-defeating end in Nietzsche's "Will to Power."