The Life of the Mind (42 page)

Read The Life of the Mind Online

Authors: Hannah Arendt

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Philosophy, #Psychology, #Politics

"The insight then to which ... philosophy is to lead us, is, that the real world is as it ought to be,"

112

and since for Hegel philosophy is concerned with "what is true eternally, neither with the Yesterday nor with the Tomorrow, but with the Present as such, with the 'Now' in the sense of an absolute presence,"

113

since the mind as perceived by the thinking ego is "the Now as such," then philosophy has to reconcile the conflict between the thinking and the willing ego. It must unite the time speculations belonging to the perspective of the Will and its concentration on the future with Thinking and its perspective of an enduring present.

The attempt is far from being successful. As Koyré points out in the concluding sentences of his essay, the Hegelian notion of a "system" clashes with the primacy he accords to the future. The latter demands that time shall never be terminated so long as men exist on earth, whereas philosophy in the Hegelian senseâthe owl of Minerva that starts its flight at duskâdemands an arrest in real time, not merely the suspension of time during the activity of the thinking ego. In other words, Hegel's philosophy could claim objective truth only on condition that history were factually at an end, that mankind had no more future, that nothing could still occur that would bring anything new. And Koyré adds: "It is possible that Hegel believed this ... even that he believed ... that this essential condition [for a philosophy of history] was

already

an actuality ... and that this had been the reason why he himself was ableâhad been ableâto complete it."

114

(That in fact is the conviction of Kojève, for whom the Hegelian system is

the

truth and therefore the definite end of philosophy as well as history.)

Hegel's ultimate failure to reconcile the two mental activities, thinking and willing, with their opposing time concepts, seems to me evident, but he himself would have disagreed: Speculative thought is precisely "the unity of thought and

time";

115

it does not deal with Being but with

Becoming,

and the object of the thinking mind is not Being but an "intuited Becoming."

116

The only motion that can be intuited is a movement that swings in a circle forming "a cycle that returns into itself ... that presupposes its beginning, and reaches its beginning only at the end." This cyclical time concept, as we saw, is in perfect accordance with Creek classical philosophy, while post-classical philosophy, following the discovery of the Will as the mental mainspring for action, demands a rectilinear time, without which Progress would be unthinkable. Hegel finds the solution to this problem, viz., how to transform the circles into a progressing line, by assuming that something exists behind all the individual members of the human species and that this something, named Mankind, is actually a kind of somebody that he called the "World Spirit," to him no mere thought-thing but a presence embodied (incarnated) in Mankind as the mind of man is incarnated in the body. This World Spirit embodied in Mankind, as distinguished from individual men and particular nations, pursues a rectilinear movement inherent in the succession of the generations. Each new generation forms a "new stage of existence, a new world" and thus has "to begin all over again," but "

it commences at a higher

lever

because, being human and endowed with mind, namely Recollection, it "has conserved [the earlier] experience" (italics added).

117

Such a movement, in which the cyclical and die rectilinear notions of time are reconciled or united by forming a

Spiral,

is grounded on the experiences of neither the thinking

ego

nor the willing ego; it is the non-experienced movement of the World Spirit that constitutes Hegel's

Geisterreich,

"the realm of spirits ... assuming definite shape in existence, [by virtue of] a succession, where one detaches and sets loose the other and each takes over from the predecessor the empire of the spiritual world."

118

No doubt this is a most ingenious solution of the problem of the Will and its reconciliation with sheer thought, but it is won at the expense of bothâthe thinking ego's experience of an enduring present and the willing ego's insistence on the primacy of the future. In other words, it is no more than a hypothesis.

Moreover, the plausibility of the hypothesis depends entirely on the assumption of the existence of

one

World Mind ruling over the plurality of human wills and directing them toward a "meaningfulness" arising out of reason's need, that is, psychologically speaking, out of the very human wish to live in a world that

is

as it

ought

to be. We encounter a similar solution in Heidegger, whose insights into the nature of willing are incomparably more profound and whose lack of sympathy with that faculty is outspoken and constitutes the actual tuming-about

(Kehre)

of the later Heidegger: not "the Human will is the origin of the will to will," but "man is willed by the Will to will without experiencing what this Will is about.""

119

Â

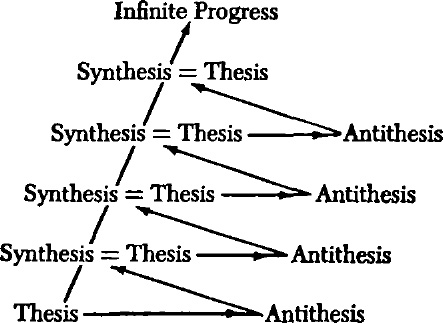

A few technical remarks may be appropriate in view of the Hegel revival of the last decades in which some highly qualified thinkers have played a part. The ingenuity of die triadic dialectical movementâfrom Thesis to Antithesis to Synthesisâis especially impressive when applied to the modern notion of Progress. Although Hegel himself probably believed in an arrest in time, an end of History that would permit the Mind to intuit and conceptualize the whole cycle of Becoming, this dialectical movement seen in itself seems to guarantee an

infinite

progress, inasmuch as the first movement from Thesis to Antithesis results in a Synthesis, which immediately establishes itself as a new Thesis. Although the original movement is by no means progressive but swings back and returns upon itself, the motion from Thesis to Thesis establishes itself behind these cycles and constitutes a rectilinear line of progress. If we wish to visualize the kind of movement, the result would be the following figure:

The advantage of the schema as a whole is that it assures progress and, without breaking up time's continuum, can still account for the undeniable historical fact of the rise and fall of civilizations. The advantage of the cyclical element in particular is that it permits us to look upon each end as a new beginning: Being and Nothingness "are the same thing, namely Becoming.... One direction is Passing Away: Being passes over into Nothing; but equally Nothing is its own opposite, a transition to Being, that is, Arising."

120

Moreover, the very infinity of the movement, though somehow in conflict with other Hegelian passages, is in perfect accord with the willing ego's time concept and the primacy it gives the future over the present and the past. The Will, untamed by Reason and its need to think, negates the present (and the past) even when the present confronts it with the actualization of its own project. Left to itself, man's Will "would rather will Nothingness than not will," as Nietzsche remarked,

121

and the notion of an infinite progress implicitly "denies every goal and admits ends only as means to outwit itself."

122

In other words, the famous power of negation inherent in the Will and conceived as the motor of History (not only in Marx but, by implication, already in Hegel) is an annihilating force that could just as well result in a process of permanent annihilation as of Infinite Progress.

The reason Hegel could construe the World-Historical movement in terms of an

ascending

line, traced by the "cunning of Reason" behind the backs of acting men, is to be found, in my opinion, in his never-questioned assumption that the dialectical process itself

starts

from Being, takes Being for granted (in contradistinction to a

Creatio ex nihilo)

in its march toward Not-Being and Becoming. The initial Being lends all further transitions their reality, their existential character, and prevents them from falling into the abyss of Not-Being. It is only because it follows on Being that "Not-Being contains [its] relation to Being; both Being and its negation are simultaneously asserted, and this assertion is Nothing as it exists in Becoming." Hegel justifies his starting-point by invoking Parmenides and the beginning of philosophy (that is, by "identifying logic and history"), thus tacitly rejecting "Christian metaphysics," but one needs only to experiment with the thought of a dialectical movement starting from Not-Being in order to become aware that no Becoming could ever arise from it; the Not-Being at the beginning would annihilate everything generated. Hegel is quite aware of this; he knows that his apodictic proposition that "neither in heaven nor on earth is there anything not containing both Being and Nothing" rests on the solid assumption of the primacy of Being, which in turn simply corresponds to the

fact

that sheer nothingness, that is, a negation that does not negate something specific and particular, is unthinkable. All we can think is "a Nothing from which Something is to proceed; so that Being is already contained in the Beginning."

123

Quaestio mihi factus sum

7. The faculty of choice: proairesis, the forerunner of the Will

In my discussion of Thinking, I used the term "metaphysical fallacies," but without trying to refute them as though they were the simple result of logical or scientific error. Instead, I sought to demonstrate their authenticity by deriving them from the actual experiences of the thinking ego in its conflict with the world of appearances. As we saw, the thinking ego withdraws temporarily from that world without ever being able wholly to leave it, because of being incorporated in a bodily self, an appearance among appearances. The difficulties besetting any discussion of the Will have an obvious resemblance to what we found to be true of these fallacies, that is, they are likely to be caused by the nature of the faculty itself. However, while the discovery of reason and its peculiarities coincided with the discovery of the mind and the beginning of philosophy, the faculty of the Will became manifest much later. Our guiding question therefore will be: What experiences caused men to become aware of the fact that they were capable of forming volitions?

Tracing the history of a faculty can easily be mistaken for an effort to follow the history of an ideaâas though here, for instance, we were concerned with the history of Freedom, or as though we mistook the Will for a mere "idea," which then indeed could turn out to be an "artificial concept" (Ryle) invented to solve artificial problems.

1

Ideas are thought-things, mental artifacts presupposing the identity of an artificer, and to assume that there is a history of the mind's faculties, as distinguished from the mind's products, seems like assuming that the human body, which is a toolmaker's and tool-user's bodyâthe primordial tool being the human hand-is just as subject to change through the invention of new tools and implements as is the environment our hands continue to reshape. We know this is not the case. Could it be different with our mental faculties? Could the mind acquire new faculties in the course of history?

The fallacy underlying these questions rests on an almost matter-of-course identification of the mind with the brain. It is the mind that decides the existence of both use-objects and thought-things, and as the mind of the maker of use-objects is a toolmaker's mind, that is, the mind of a body endowed with hands, so the mind that originates thoughts and reifies them into thought-things or ideas is the mind of a creature endowed with a human brain and brain power. The brain, the tool of the mind, is indeed no more subject to change through the development of new mental faculties than the human hand is changed by the invention of new implements or by the enormous tangible change they effect in our environment. But the mind of man, its concerns and its faculties, is affected both by changes in the world, whose meaningfulness it examines, and, perhaps even more decisively, by its own activities. All of these are of a reflexive natureânone more so, as we shall see, than the activities of the willing egoâand yet they could never function properly without the never-changing tool of brain power, the most precious gift with which the body has endowed the human animal.

The problem we are confronted with is well known in art history, where it is called "the riddle of style," namely, the simple fact "that different ages and different nations have represented the visible world in such different ways." It is surprising that this could come about in the absence of any physical differences and perhaps even more surprising that we do not have the slightest difficulty in recognizing the realities they point to even when the "conventions" of representation adopted by us are altogether different.

2

In other words, what changes throughout the centuries is the human mind, and although these changes are very pronounced, so much so that we can date the products according to style and national origin with great precision, they are also strictly limited by the unchanging nature of the instruments with which the human body is endowed.