The Lights of Pointe-Noire (3 page)

Read The Lights of Pointe-Noire Online

Authors: Alain Mabanckou

One thousand and one nights

F

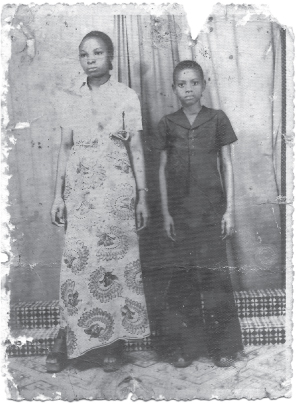

or a long time, then, I let people think my mother was still alive. In a way I had no choice but to lie, having picked up the habit way back in primary school when I brought my two older sisters back to life in an attempt to escape the teasing of my classmates, who were all very proud of their large families, and offered to âlend' my mother their offspring. Obsessed with the idea of bearing another child, she consulted the town's most noted doctors, as well as most of its traditional healers, who claimed to have treated women who'd been sterile for twenty years or more. Disappointed in the white men's medicine, and cheated by the crooks in the backstreets of Pointe-Noire, who had never healed so much as a scratch with their spells and sorcery, my mother resolved to accept her condition: mother of a single child, she told herself there were other women on this earth who had no children at all, and would have been delighted to be in her shoes. But she still couldn't just sweep aside the fact that the society she lived in considered a woman with one child as pitiful as a woman who had none. Similarly, an only son was a pariah. He was the cause of his parents' misfortune, having âlocked' his mother's belly behind him, so he could be an only one, enjoying this lowly distinction which the community scorned. He was also said to have special powers: he could make it rain, he could stop the rain, bring fever on his enemies, and prevent their wounds from healing. He was all but assumed to have power over the rotation of the earth.

I was quite prepared to believe all this, and searched in vain for the hidden powers I was thought to possess, finally concluding that what an only child really possessed was the secret fortune to be gained from his parents' constant fear they might lose him. The parents were convinced that he belonged to another world, he was bored in theirs and that all the toys in the world could never make up for that boredom. The sisters I resuscitated in their entirety became my only armour, reliable characters in an imaginary world where I felt at ease and where, for once, I could act like an adult, and not depend on others to take care of me.

When I mentioned my sisters to my friends, I probably exaggerated. I proudly made out they were tall, beautiful, intelligent. I confidently added that they wore rainbow-coloured dresses and spoke most languages known on earth. And if anyone doubted me, I'd tell them they rode round in a red Citroën DS convertible, driven by their hired boy, that they'd flown in planes more times than they could count, and had sailed across seas and oceans. I knew I'd scored a point when the questions began:

âSo, have you been in the Citroën DS with your sisters?' asked the most outspoken of my playmates, his eyes gleaming with envy.

Quickly I found the perfect alibi:

âNo, I'm too small, but they've promised they'll let me when I'm as tall as themâ¦'

Another, spurred by jealousy, I expect, would counter:

âYou're making it up! Since when did you have to be big to get in a car? I've seen kids smaller than us in cars!'

I kept my cool:

âYeah, but was it in a Citroën DS you saw them?'

âUm, no ⦠a Peugeotâ¦'

âWell, there you go! To get in a Citroën DS convertible you have to be bigger than us because it's a really fast car, it's dangerous if you're still littleâ¦'

No one in the group of kids had ever seen these sisters, and as my mythomania grew, so did their disbelief, and their questions rained down on me like gunfire. They were in Europe, I said, in America, or maybe Asia, they'd come back for a holiday in the dry season.

âCan we meet them? Will they play with us?' they all chorused.

âOf course, I'll introduce them to you, but they're too big to play with us.'

Caught in the web of my own fictions, I started to believe in them more than my friends did, and I awaited the return of my siblings with quiet confidence. I kept a lookout for planes, tracked every Citroën DS in town, and to my great despair, found not a single convertible. The day I did see one, my disappointment was huge: it was black, and driven by a white couple with no child on boardâ¦

I was heard talking to myself on the way to school or in our neighbourhood, when my mother sent me to buy salt or paraffin. I'd spent so much time with my sisters in my head that now I saw them opening the door of the house at night, coming inside, going through to the kitchen, rooting among the pans and the leftovers of the food my mother had made. One day I whispered to my mother that my sisters had come to see us and found nothing to eat; she was silent for a moment, then, as though she found all this quite normal and was surprised I had only just noticed their nocturnal visits, she said:

âHave you never noticed I leave two full plates out every evening, at the entrance to the house?'

âI thought they were for Miguelâ¦'

She tried not to laugh:

âNo, they're not for the dog, though he does sometimes finish what your sisters leave.'

âOne of them had a yellow dress on and the other had a green blouseâ¦'

âShush! Don't tell anyone, not even your father, or they'll stop comingâ¦'

The day after this conversation my mother left out two dishes of beef and beans with two glasses of orange juice. I stood behind her to make sure she gave the sisters the same food as I'd had and that my older siblings each got the same amount, so they wouldn't squabble. If I thought one had more than the other I would move a piece of meat over to the other plate, to even things up, while my mother looked on with a small smile of satisfaction.

In the morning I rushed out of the door to find that the two plates were still in the same place where my mother had left them. My sisters hadn't touched their food. I shouted to Maman Pauline just as she was coming out of her room:

âThey haven't eaten!'

âYes they haveâ¦'

âThe food's still on the plates!'

âWell, yes, it would be⦠It looks to you like there's food on these plates, but in fact there's nothing there. They're empty.'

âBut I can see there's food on them!'

At this, as though anxious to cut short this conversation, which could have continued for some time, she asked:

âIf there's food on these plates, then tell me this, why didn't Miguel eat it?'

âI don't know butâ¦'

âDogs can see things that we can't. Miguel knows there's nothing on the plates, your sisters have had a feastâ¦'

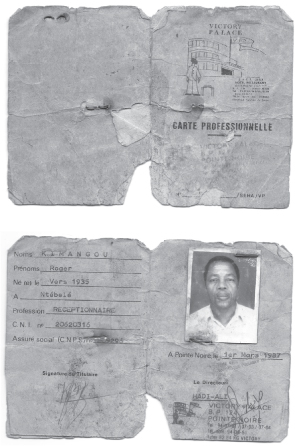

One evening, I was delighted to be given an apple that my father had brought back from the Hotel Victory Palace where he worked as the receptionist. I decided to show my gratitude by revealing the secret of my sisters' apparitions.

âI swear it, I saw them with my own eyes, clear as I see you now, Papa! And, when they eat, us humans can't see that they've eaten, only dogs can! You do believe me, don't you?'

He listened to me calmly as I babbled on, even acting out my sisters' movements. When I'd finished my somewhat incoherent account, which he took for the ramblings of a rather over-talkative child, I felt bad for having said too much, and broken my pact with these two characters.

âDon't tell Maman I told you the secret. She'll be cross with meâ¦'

I could tell he would talk to my mother about it because he didn't promise not to. All I got was a quick nod of the head before he went off to join my mother in the bedroom. I heard Maman Pauline's laughter, then, in a hushed voice, âDon't laugh loud like that, he'll hear youâ¦'

I had actually just lost the naivety which had made it possible for me to steer my way between the real world and the imaginary, to inhabit both without being paralysed by the wall of doubt which was a feature of the adult domain. I was sure I had lost the pleasure of talking with my sisters because I had not held my tongue. This made me terribly sad.

Those next few days, whenever I got up in the middle of the night to look out for my sisters, I found myself face to face with Miguel. His hair bristled and he quivered, pointing his nose towards the street, his way of telling me that the two people had just left, because they didn't want to talk to me now I had revealed their nocturnal presence to Papa Roger. I was angry with myself, and my attitude towards my father changed. I think it was at this time that I began to cultivate the art of silence, to tell myself that anything I said would only make things worse. I spoke less and less of my sisters to my friends, and they stopped asking me. It was all over, they knew that, it was time I became a normal kid again.

Sitting in front of the door to our house, I watched Miguel, who looked as teary-eyed and sad as I did. I no longer knew what he meant when he wagged his tail. I expect he was trying to comfort me. Maybe he could help me recapture the joy I'd got from thinking I too belonged in that other world, the one he sensed with his canine intuition, the instinct God gave him instead of the gift of speech, which he'd given humans.

To redeem myself in my sisters' eyes, I secretly ate the food my mother continued to leave out for them each night, by the door, and told myself that whatever went into my stomach also went into theirs. In the morning, my mother was astonished to find the empty plates, and would reprimand Miguel, who would turn to me with a look of red-eyed reproach. But when I gently stroked him he at once grew calm, for he alone understood the true depth of my sadnessâ¦

My father's glory

M

y father was a small man, two heads shorter than my mother. It was almost comic, seeing them walking together, him in front, her behind, or kissing, with him standing up on tiptoe to reach. To me he seemed like a giant, just like the characters I admired in comic strips, and my secret ambition was one day to be as tall as him, convinced that there was no way I could overtake him, since he had reached the upper limit of all possible human growth. I realised he wasn't very tall only when I reached his height, around the time I started at the Trois Glorieuses secondary school. I could look him straight in the eye now, without raising my head and waiting for him to stoop down towards me. Around this time I stopped making fun of dwarves and other people afflicted by growth deficiency. Sniggering at them would have meant offending my father. Thanks to Papa Roger's size I learned to accept that the world was made of all sorts: small people, big people, fat people, thin people.

He was often dressed in a light brown suit, even when it was boiling hot, no doubt because of his position as receptionist at the Victory Palace Hotel, which required him to turn out in his Sunday best. He always carried his briefcase tucked into his armpit, making him look like the ticket collectors on the railways, the ones we dreaded meeting on the way to school

when we rode the little âworkers' train', without a ticket. They would slap you a couple of times about the head to teach you a lesson, then throw you off the moving train. The workers' train was generally reserved for railway employees, or those who worked at the maritime port. But to make it more profitable, the Chemin de fer Congo-Océan (CFCO) had opened it to the public, in particular to the pupils of the Trois Glorieuses and the Karl Marx Lycée, on condition they carried a valid ticket. As a result they became seasoned fare dodgers, riding on the train top, in peril of their lives. It was quite spectacular, like watching

Fear in the City

at the Cinema Rex, to see an inspector pursuing a pupil between the cars, then across the top of the trainâ¦

Papa Roger walked with a lively step, his eyes glued to his watch â which made my mother say he was the most punctual man on earth. With him everything was timed to the exact minute. He left the house at six in the morning, took the bus on the Avenue of Independence, opposite the Photo Studio Vicky, and arrived in the centre of town half an hour later.

At seven o'clock on the dot he was in the reception of the Victory Palace, straight as a rod, greeting the first clients of the day, as they made their way to the restaurant for breakfast. He stood at the desk and scanned from the hotel entrance to the street outside. As soon as he saw a new client getting out of a car, he shook a little bell. Two uniformed employees came running up to the main entrance, grabbed their suitcases and deposited them at reception. They then took them up to the upper floors after my father had filled out the registration forms and assigned them a room. He took a sly pleasure in describing this procedure to us at table in the evening. It was difficult for him to conceal a kind of pride which, in my mother's eyes, was nothing but bluster. He would stop in the middle of eating and crow:

âI'm the most important employee at that Victory Palace! It's me, no one else, who decides what room to put a client in! If they look like a jerk â you get a lot of them with these Europeans on holiday â I don't offer them the good room with the view of the garden. I keep that for the clients I like, the regulars who come back every year. Sometimes I might give someone a bad room to start off with, if I don't know them, and then if they're nice to me during their stay I'll switch them. They usually remember I've done that when they leave, and they'll give me a big tip!'

He got back from work at five in the evening, bringing a few French magazines, which he read at table after dinner, reacting out loud to what he read:

âWhat? Not possible! I don't believe it! Why on earth did they do that? The French are mad!!'

At the weekend he wore white pyjamas with red stripes, and brown slippers that were too big for his feet. They were a present, he reminded us, from his boss, Mme Ginette.

âEven if they were too small for me, I'd wear them, a present's a present! They're called

charentaises

, no one else in this town has them! They're so splendid, I know people who'd wear them to go walking round town in, if they had a pair! But they're meant for staying at home in, and reading the paper. That's what they do in Europe!'

He'd sit down on the doorstep in the morning, and continue his perusal of the newspapers that sat in a pile next to him, with a stone on top, to stop them blowing away in the wind. He forgot to drink the coffee my mother set down just next to him, concentrating on turning the pages, turning back to something he'd read a few minutes before and grabbing a red pen to scrawl on it. Then he'd suddenly break off reading, glance over at me, and notice I was sitting there under the mango tree with my jaw dropping in admiration.

âYou want to read with me? Come on, then!'

I'd dash over to him, having waited impatiently for this moment. He read to me what he called the âworld news'. I quickly learned the more complicated names of foreign countries and their leaders. Europe, America, Asia or Oceania ceased to feel like distant lands. I noticed my father used his red pen to underline the more difficult French words.

âI'll check those words on Monday in the dictionary at the Victory Palace⦠I need to learn them so I can use them at the right moment with the clients.'

Picking out two more, and underlining them irritably, I heard him grumble:

âI don't understand why people don't write simply, why they have to write words no one understands!

Antediluvian

, for example, or

apocryphal

, what's that mean?'

Indignantly, he turned the page. Here was the world news. He looked displeased as he grumbled:

âFor goodness' sake, the French are crazy! Why don't they talk about what's happening in our country? We've had a

coup d'état

here, and there's not one line about it! President Marien Ngoubai was murdered last week! The French are in league with them, they must be, they can't possibly not mention it! The French are behind the whole thing!'

Seeing I said nothing, he went on:

âI'll tell you something, my boy, now you listen to Roger! They don't talk about us because our country's too small! And because it's too small, people forget about it, and think it's only other countries that have mosquitoes, and poverty and civil wars. Not true! We've got every problem there is here, you only have to look around you! It's always the same, in the sea people only think about the sharks and the whales, because they make all the noise! No one thinks about the small fry who are just there to get eaten by the big fish!'

My mother became aware of my increasing fascination with Papa Roger and his reading, and began to get a little jealous. As soon as my father was gone she grabbed hold of the newspaper and withdrew to a corner of the yard with her back to a mango tree, saying:

âDon't disturb me, I'm reading!'

She looked like

Reading Woman

by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. How had she managed to hide from me for so long that she knew how to read? She concentrated hard, checking out of the corner of her eye that, like my father, she had my attention.

The next time this happened, I went over to her and realised she was holding the newspaper upside down. I pointed this out to her with a mocking smile. Unruffled by what she perceived to be an insult, she looked me up and down, returned the mocking smile and said:

âDo you really think that I, Pauline Kengué, daughter of Grégoire Moukila and Henriette N'Soko, am so crazy I'd read a paper upside down? I did it deliberately to see your reaction! Don't you go thinking you and your father are the only ones in this house who know how to read and write!'

On the outside, nothing has changed, apart from the air-conditioners fitted above the windows and the satellite dishes on the roof. Built in the late 1940s, in the centre of town, a short distance from the Côte Sauvage and the railway station, the Victory Palace is one of the oldest hotels in Pointe-Noire. In 1965, the first owner, M. Trouillet, handed over the management to Ginette Broichot, and she bought it from him in 1975. Since it was first erected, the building has watched from a distance as new constructions go up around it, and with slight arrogance preserves the typical structure of that time, concrete, with a huge white façade at the corner of Rue Bouvanzi and Avenue Bolobo.

I don't dare enter the building, as though I fear my father's ghost might be lurking somewhere, resenting this return to his past, which is also, indirectly, my own. I recall how he used to boast that he was the doyen of this hotel, and the most loyal member of its staff. The proof of this lay in his special treatment by Mme Ginette, who never raised her voice to him, while the rest of the staff lived in fear of the wrath of the French boss. Madame Pauline thought Papa Roger's monthly salary was twice what it really was, when in fact he was constantly asking for an advance or counting on getting tips from the clients. He had managed to get my maternal uncle, Jean-Pierre Matété, a job as a room boy. In the summer, Marius, one of my âhalf-brothers', and I worked cleaning rooms and washing dishes. Sometimes, if she went back to France on holiday, Mme Ginette would put him in charge of the hotel. During these periods he stepped into the boss's shoes and ran the place with an iron fist. If anyone's uniform wasn't perfect he would tell them off, and he shouted at the gardener if he was late watering the plants. Papa Roger didn't mince his words, calling some people ignorant, others bastards, and writing their names down in his notebook so he could report back to Mme Ginette when the time came. The employees secretly longed for the boss to return as soon as possible, since being shouted at by a Negro was worse than being shouted at by a white.

I will never forget the time he fell into a deep gloom, when the stories he brought home from work, and which my mother and I adored, dried up. It turned out Mme Ginette's father had come over from France, and was staying at the Victory Palace indefinitely. My father was convinced that his boss had finally found a hidden way of imposing a ruthless inspector on the staff, and this he was not prepared to tolerate. An elderly, sharp-eyed man, he sat in the lobby all day long, watching what went on. Papa Roger claimed that his own role had been diminished, that the atmosphere of the hotel was being ruined by what he called âthe intruder'. Employees mustn't take anything home, not even an apple. Newspapers, which my father usually slipped into his bag when the whites had finished reading them, had to stay in the hotel, till eventually they were thrown out. The boss's father would openly stand behind a client so he could hear whether Papa Roger handled the conversation properly.

âEvery day, he's there, watching us, he tells the

patronne

everything, and then she comes and ticks us off, like children! Is that the way to do things?' he'd ask my mother.

She'd stay quiet as a clam, and probably couldn't see why it bothered my father so much. Then, feeling she ought to say something, she just mumbled:

âWell, after all, it is his daughter's hotel⦠So it's his hotel too!'

âOh right, so what are we, then? Was it him that gave me the job or his daughter? Anyway, it won't last long, we're going to sort him out next weekâ¦'

The plan, inspired by my father, in collusion with several employees, was carried out on Monday morning, after heated discussion the previous day, during which they had to convince a few cowards who thought if they went this far they might be sacked without pay. But what really mattered to my father was his territory. He would rather be sacked than submit each morning to the watchful eye of the âintruder'.

They discreetly brought a plant into the Victory Palace known as â

kundia

'. It had powerful spikes, invisible to the naked eye. Seen through a microscope, they looked like rows of bristling needles, which came away on contact with a foreign body. Farmers used them round the edges of their fields to stop animals or thieves taking the fruit of their crops. If it accidentally brushed your skin, the only thing to do was resist the temptation to scratch for as long as possible, because the more you scratched, the deeper the teeth of the

kundia

dug into your skin, and the agony could last for an hour or more.

One of my father's sidekicks put on a pair of gloves and scattered the

kundia

bristles on the âintruder's' armchair. Papa Roger's role, from this point on, was to make sure no one but the intruder sat there.

The old man came down from his room in his bermudas around ten in the morning. First he did his round of the restaurant, examining each table, straightening a chair he judged out of line, or giving orders to the waiters. Only once he had completed his tour, which for him had become a tradition, and for the employees a form of torture, did he finally take his breakfast.