The Lights of Pointe-Noire (5 page)

Read The Lights of Pointe-Noire Online

Authors: Alain Mabanckou

Death at his heels

I

never felt I really knew Papa Roger very well, partly because he told me nothing about his own parents. I didn't know whether they were alive, or had passed on into the next world. Nor had I ever set foot in Ndounga, his native village. This didn't bother me, as I cultivated a visceral hatred for anything connected to any paternal branch, my natural father having cleared off when my mother needed him. To me Papa Roger was father and grandfather, the perfect paternal rootstock, resistant to wind and weather, bringing forth fruit in every season. So I had given up desperately trying to find out about my paternal forebears.

I owe it to Papa Roger that my childhood was scented with the sweet smell of green apples. This was the fruit he brought home for me every week from the Victory Palace Hotel. In our town it was a great treat to eat an apple. For us it was one of the most exotic fruits to come from the colder regions. As I bit into it, I felt I was sprouting wings that would carry me far away. I'd sniff the fruit first, with my eyes closed, then munch it greedily, as though I was worried someone would suddenly come and ask me for a bite and spoil my pleasure in crunching it down to the last little pip, since no one had ever taught me how to eat an apple. Papa Roger stood there in front of me, smiling. He knew he could get me to do anything he wanted by simply giving me an apple. I'd suddenly turn into the most talkative boy on earth, even though I was by nature rather reserved. My mother realised the havoc an apple could wreak in my behaviour. She'd fly into one of her rages, usually at my expense, which to this very day tarnishes my pleasure in that delicious smell:

âThere you go again, telling your father all sorts when you've eaten an apple! I'll start to think they're alcoholic, and have to ban them!!'

âI didn't do anything!'

âI see, so why did you tell him I went out with someone this afternoon, then? Don't come asking me to get your supper tonight! Let that be a lesson to you!'

It was true, I had been rather indiscreet that day, whispering to my father that a slim, tall man had dropped by our house, talked with my mother, after which the two of them had gone to a local bar for a drink. At this my father flew into a rage and yelled at my mother:

âI thought so! It's that guy Marcel, isn't it? You said it was all over between you and that imbecile! More fool me!'

My father refused to sit down at table with us that day, and shut himself up in the bedroom. Marcel was someone Maman Pauline had met around the same time she met my father, but she must have made the choice she did because Marcel was a seasoned womaniser who believed women fell at his feet because he had a great body. According to my mother, nothing happened between them. She took a fistful of earth in her right hand, scattered it in the air, which meant, in our tradition, that she swore she had told me the truth, the whole truth, nothing but the truth; you couldn't mess around with this custom, it had been used by our tribe since the dawn of time. Anyone who swore like this when in fact they'd been lying got a terrible headache the next day, and sometimes had to stay in bed for days on end. First they vomited, then their skin dried up. My mother did not develop any of these symptoms over the next few days. So I decided to believe her version, and let drop Papa Roger's, even though somewhere deep down I still wasn't sure.

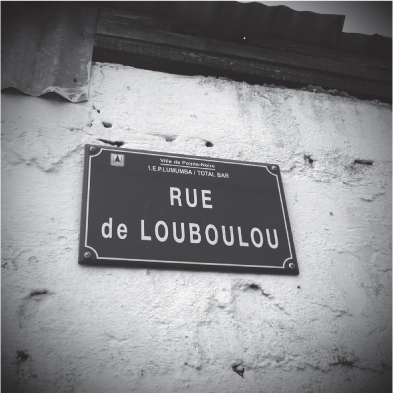

Papa Roger was convinced Marcel was still after my mother and that something was going on between them, something lasting, perhaps, since he seemed to reappear every two or three years. When I was eight or nine years old, a really memorable fight broke out between the two men in the rue de Louboulu, in the Rex district. This was Uncle Albert's turf, he worked as a civil servant for the National Electricity Company and had been the first person on my mother's side of the family to emigrate from the village of Louboulou to Pointe-Noire. It was because of him we had all come to live in Pointe-Noire, with the exception of my mother, who made her own way here, to try to forget my natural father. Uncle Albert had come first, and once he'd set himself up he sent for his younger brother, Uncle René. After that his younger sisters arrived â my mother's older sisters â Aunt Dorothée and Aunt Sabine. When my mother arrived she brought with her the youngest of all the brothers and sisters, Uncle Mompéro. And as my maternal grandfather Grégoire Moukila was polygamous â twelve wives and more than fifty children â Uncle Albert gradually assembled them all at the rue de Louboulu, as his own professional position became more secure. Another of my uncles, who I was very close to, arrived by this route, Jean-Pierre Matété, who had the same father as my mother. With so many members of the family living in this street, Uncle Albert got the authorities to agree to change the name to rue de Louboulu, in honour of this small corner of the Bouenza district, of which our grandfather, Grégoire Moukila, became chief in the mid-1900s. In a way the street was like our own village. Most of the houses had been built by people from our district, though in later years some of them had sold their homes, gradually allowing people we didn't know to move in. Because my uncle worked in electricity everyone got free power. A wire simply had to be passed from one household through to the next, and suddenly we went from storm lantern to light bulb, from coal iron to electric iron.

The city council agreed to Uncle Albert's request, after he'd paid backhanders to a few of the government employees who then came and raised their glasses, shamelessly, at the renaming ceremony for the street. Every week members of the family would drop in to see Uncle Albert, and when he withdrew into his bedroom you knew he would re-emerge with some money to give the visitor. Broadly speaking, though it was not to be said out loud, you went round to Uncle Albert's in the hope of leaving again with a few thousand CFA francs. If people arrived while he was having his siesta they would hang around in the yard, pretending to chat with Gilbert and Bienvenüe, my uncle's twins, my cousins, with whom I spent much of my childhood. The twins understood what was going on, and sensed that their father was basically the family bank. Sometimes, so he wouldn't be disturbed while he was resting, Uncle Albert would place a packet of banknotes on the table and leave it to his wife, Ma Ngudi, to distribute them to the various visitors.

My mother would also stop off at the rue de Louboulu. Not to pick up money, but to hand some over to Ma Ngudi, because I sometimes lived at my uncle's for a while. Maman Pauline had requested this, âin the interests of Albert's nephew'. Ma Ngudi was said to be good with children who didn't eat enough â sometimes I would eat only the meat, and leave the fufu and manioc.

One evening my mother came to pick me up at Uncle Albert's, and Marcel, my father's bête noire, just happened to be hanging around close by. By pure coincidence, Papa Roger, on his way back from work, had also decided to thank my uncle and his wife for having me to stay with them, and probably to leave a little envelope for my cousins Bienvenüe and Gilbert, as he often did.

My mother and I were still saying goodbye to Uncle Albert when we heard a great rumpus out in the street. It had to be a fight, because all the kids in the neighbourhood were shouting:

âAli boma yé! Ali boma yé! Ali boma yé!'

It was the famous cry of the Zaireans at the âMay 20th' Stadium during the legendary fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. In both Congos, it had become customary to chant it at any brawl.

We all dashed outside into the street, and found a real punch-up going on, which had brought the entire Rex neighbourhood running to the rue du Louboulou. Marcel and my father were on the ground, covered in dust, and Papa Roger was on top, despite being so much smaller than the other guy, who seemed to me to be some kind of colossus, measuring nearly two metres, a good head taller than most houses in the street. Each time Marcel tried to get to his feet and catch my father off guard, the local people, including several members of our family, caught hold of his shirt or one of his feet, and he lost his balance again, to Papa Roger's advantage. Picking a fight in the middle of this group, where we were as good as joined at the hip, was equivalent to signing his own death warrant.

My mother yelled at the top of her voice:

âRoger! Leave the guy alone! He hasn't done anything!'

My father wouldn't let go of Marcel's neck.

âI'll kill him! I'll kill him!'

Buoyed up by the excitement of the group, he was leaping around, striking karate poses which he'd seen in the film

The Wrecking Crew

, butting him, kicking him, kneeing him, and again, till Marcel, his face all bloodied, managed to work himself free and make a run for it. The whole neighbourhood ran after him. Everyone had a piece of wood or a stone in their hands.

âThey'll kill him!' shrieked my mother.

âWe sure will!' came a voice from the crowd.

You couldn't tell who was throwing the stones and who the bits of wood, which Marcel was just managing to dodge. He had long legs and ran as though death itself was at his heels. In a few strides he crossed the Avenue of Independence and vanished into thin air in the winding streets of the Trois-Cents neighbourhood, the haunt of the prostitutes from Zaire. His pursuers knew not to go looking for him on that territory, where a fight could quickly turn into a general riot.

Back at our house, my parents were rowing fiercely. My mother was telling my father it was a coincidence that Marcel happened to be in the rue de Louboulou. My father didn't believe her, and was convinced that Maman Pauline had arranged a meeting with him, and that Uncle Albert was in on it, as were the entire Bembé tribe in the rue de Louboulou.

âSo then why did the very people from my tribe that you're accusing take your side?'

My father didn't answer that. Proof, perhaps, that he realised my maternal family had been rooting for him, and he'd been carried away by suspicion and rageâ¦

My mother is a miss

T

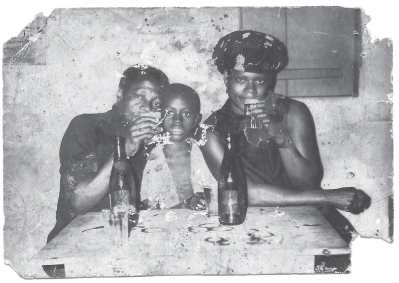

he photo's in black and white, with a bit torn off at the bottom, on the right-hand side. It was taken at the end of the 1970s, one afternoon in the Joli-Soir district. I had come to meet my parents in this bar, where we are all sitting at a table. The two of them have glasses raised to their lips, and mine is on the table. It's filled with beer, my mother insisted on this, she didn't want anyone to think I was only there for the photo. We had to make it look like I had been sitting drinking with them for some time. I can still hear my mother acting like some finicky film director, to the photographer's slight surprise:

âHold on, monsieur, we're not ready! First get rid of those flies buzzing round the table! A fine way to mess up people's photos! I'll tell you when to press the button!'

She swept her eyes across the room, hoping she could put off the moment when he took the picture. A few people entered and were making their way to the back of the bar. She grabbed her chance:

âWhat's all this, then? Did you see that? You can't even take a photo in this country these days, not since President Marien Ngouabi died! Tell them to stop coming in for a moment!'

Then, turning her attention to us:

âAnd you two, act as though the photographer wasn't there! Especially you, Roger, whenever someone takes your photo you look all tensed up like a snail that doesn't know which way to turn! What way is that to behave? And you, boy, sit properly now. Sit up straight like a boy scout, like a boy who's proud to be sitting there between his papa and mama!'

Despite all these precautions, at which the photographer's annoyance grew, she failed to notice a fourth glass on the table, to my left, in front of Papa Roger. He had bought a drink for the photographer, who had knocked it back in one, without saying thank you, eager to get on with the serious business. Instead of moving his glass out of the way, he had left it there. He seemed completely overwhelmed by his job, which, in order for him to make any money at all, required him to go all round town, from one bar to another, persuading people to have their photos taken. He wrote down your address in an old notebook and came round to your house the next day with the picture. You had to pay him a deposit beforehand. He made sure to print several copies of the same image, since if it turned out to be a masterpiece, everyone was going to want one. He was known in most districts of Pointe-Noire by now. And that day he was blowing his own trumpet in front of my parents, saying:

âI'm the only one in this town with a Hasselblad SWC! Even the Americans used one when they went up into space! Do the other photographers in this town have one? No they do not! Just me! That's why they call me Mr Hasselblad SWC!'

Could anyone verify his claims? No one understood his gibberish anyway, all you saw was him pressing a button, and a flash that went off just like on any other camera. But my mother cut him short:

âStop prattling and tell us how much the photo costs!'

Mr Hasselblad SWC struck up a ridiculous pose with his camera and, in the blink of an eye, the flash exploded in our facesâ¦

The photo looks different to me now. Perhaps because I'm looking at it in the town where it was taken. It's as though in Europe or in America it keeps its secrets hidden. I look more closely. My mother dominates the picture. All you see, practically, is her and the scarf round her head. She seems more relaxed than my father and I, who are both trying to squeeze into the small amount of space she's left us. She wanted to be the one people saw when they looked at the photo. We were just there to highlight her presence, the principal's impact being very much dependent on the involvement of those playing the secondary roles. This was clearly the impression she wished to create, with the way she is leaning slightly to the right, as though my father and I no longer existed, or as though we were intruding on what she considered her moment of glory, which she would leave for posterity.

She is looking at the camera lens with a little smile, showing she has found the perfect pose. She doesn't know I've got my mouth open, a blank expression, big wide eyes that seem to be asking what the point of this photo is. Normally she would have reminded me:

âSit up straight, look, we're having our picture taken!'

She'd have told me to close my mouth, she didn't like this expression, considering it unworthy and unflattering.

My shirt is hanging open â perhaps I had lost my buttons again, âlike an idiot', as my mother would have said. I admit that buttoning up my shirt was not a priority. I often had my shirt with all the buttons in the wrong holes.

Now I notice various details that I haven't seen before. For example, my mother's right shoulder seems to be crushing me, while my father's trying to keep us propped up. That's why his head is pressed up against mine. I can see, too, my father's fingers on my mother's left shoulder. I think it must be his left arm holding us up and without it we wouldn't have managed to hold the pose. Lastly, the marks left by the bottles on the surface of the table suggest the waiters didn't wipe them very oftenâ¦