The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition (11 page)

Read The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition Online

Authors: Daniel J. Wallace

My physician interview begins by asking why the patient has come and how

he or she feels. Once the patient’s symptoms and history are heard, I conduct

[60]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

a ‘‘review of systems.’’ As many as a hundred questions can be asked as part

of this screening process. Positive responses may lead to an additional set of

queries that clarify symptoms in a given area, such as how long the complaint

has been present, what makes it better or worse, how it has been diagnostically evaluated and treated in the past, and what is its current status.

The patient will be asked about allergies, and his or her and family members’

history of rheumatic disease or other diseases. Other relevant facts include possible occupational exposures to allergic or toxic substances, educational attain-ment, and with whom the patient lives. Unusual childhood diseases will also be

explored, as well as alcohol and tobacco use, previous hospitalizations and surgeries, past and current prescription or over-the-counter medications that are

frequently used. Not only do certain environmental and family histories predis-

pose people to lupus, but this line of questioning forms the basis of a psycho-

social profile that may be important in developing a productive doctor-patient

relationship.

The rheumatic review of systems covers these eleven categories:

1.

Constitutional symptoms

, such as fevers, malaise, or weight loss, are dealt with first. They refer to the patient’s overall state and how he or she feels.

This is followed by an organ system review that goes from head to toe.

2. The

head and neck

review includes inquiries about cataracts, glaucoma, dry eyes, dry mouth, eye pain, double vision, loss of vision, iritis, conjunctivitis, ringing in the ears, loss of hearing, frequent ear infections,

frequent nosebleeds, smell abnormalities, frequent sinus infections, sores

in the nose or mouth, dental problems, or fullness in the neck.

3. The

cardiopulmonary

area is covered next. I ask about asthma, bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, pleurisy (pain on taking a deep breath), shortness of breath, pneumonia, high blood pressure, chest pains, rheumatic

fever, heart murmur, heart attack, palpitations or irregular heartbeats, and

the use of cardiac or hypertension medications.

4. The

gastrointestinal

system review includes an effort to find any evidence of swallowing difficulties, severe nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, unusual eating habits, hepatitis, ulcers, gallstones, blood in stool

or vomit, diverticulitis, colitis, or pancreatitis.

5. The

genitourinary

area must be approached in a respectful, sensitive way.

Aside from inquiring about frequent bladder infections, kidney stones, or

blood or protein in the urine, I also review any history of venereal dis-

eases (including false-positive syphilis tests) and, in women, the obstetric

history, with special attention to miscarriages, breast disorders and sur-

geries (cosmetic and otherwise), and menstrual problems.

6. Next,

hematologic and immune

factors that the patient may be aware of

History, Symptoms, and Signs

[61]

include how easily he or she bruises, anemia, low white blood cell or

platelet counts, swollen glands, or frequent infections.

7. A

neuropsychiatric

history takes into account headaches, seizures, numbness or tingling, fainting, psychiatric or antidepressant interventions, sub-

stance abuse, difficulty sleeping, and—most important—what is called

‘‘cognitive dysfunction,’’ a subtle sense of difficulty in thinking or artic-

ulating clearly.

8.

Musculoskeletal

features involve a history of joint pain, stiffness, or swelling, gout, muscle pains, or weakness.

9. The

endocrine

system review will include questions about thyroid disease, diabetes, or high cholesterol levels.

10. The

vascular

history may uncover prior episodes of phlebitis, clots, strokes, or Raynaud’s (fingers turning different colors in cold weather).

11. Finally, the

skin

is discussed. The skin is a major target organ in lupus, and evidence of sun sensitivity, hair loss, mouth sores, the ‘‘butterfly

rash,’’ psoriasis, or other rashes is carefully reviewed.

In concluding the history taking, I always ask a patient whether there is any-

thing I should know that was not covered. Ed Dubois, my mentor, dedicated

his lupus textbook to ‘‘the patients, from whom we have learned.’’ Physicians

become better doctors when they listen to what patients have to say about things that the doctor may not have brought up. Occasionally, the patient hits on something in casual conversation that turns out to be quite important in shedding

light on her disease.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history and review of systems elucidate what physicians call

symptoms

; a physical examination reveals

signs

. Four methods known as inspection (looking at an area), palpation (feeling an area), percussion (gentle knocking against a surface such as the lung or liver to detect fullness), and auscultation (listening with a stethoscope to the heart, chest, carotid artery, etc.) are employed during the physical. You will be evaluated from head to toe.

First,

vital signs

are checked to ascertain weight, pulse, respirations, blood pressure, and temperature. The

head and neck

exam includes evaluation of the pupils’ response to light, eye movements, cataracts, and the vessels of the eye.

The ear exam searches for obstruction and inflammation. The oral cavity is

screened for sores, poor dental hygiene, and dryness. I palpate the thyroid and the glands of the neck and also listen to the neck for abnormal murmurs or

sounds (carotid artery bruits). The

chest

examination consists of inspection (e.g., for postural abnormalities), palpation for chest wall tenderness, percussion to

[62]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

evaluate fluid in the lungs, and auscultation (e.g., to rule out asthma and pneumonia). The

heart

is checked for murmurs, clicks, or irregular beats. The

abdomen

is inspected for obesity, distension, or scars; palpated for pain or hernia; percussed to assess the size of the liver and spleen; and auscultated to rule out any obstruction or vascular sounds. This is followed by an

extremity

evaluation, which includes looking for swelling, color changes, inflamed joints, and deformities. Specific maneuvers allow me to assess range of motion, muscle strength, pulses, reflexes, and muscle tone. If indicated, a

genitourinary

evaluation is done. It includes a breast examination, rectal evaluation, pelvic examination,

and—in women—pap smear. In rheumatology, a genitourinary exam is neces-

sary only if the patient has breast implants, complains of vaginal ulcers, or has other symptoms relevant to these areas. A

neurobehavioral

assessment that will reflect change in the nervous system is usually conducted as part of the ongoing conversation; necrologic deficits can be detected by observing the patient for

tremor, gait abnormalities, or abnormal movements or reflexes. If necessary, a

more formal mental status examination may be conducted. Finally, the

skin

is examined for rashes, pigment changes, tattoos, hair loss, Raynaud’s, and skin

breakdown or ulcerations.

The physical examination may include other steps as well, depending upon

the problems reported and the nature of the consultation. A thorough physical

examination conducted after a detailed interview allows me to order the appro-

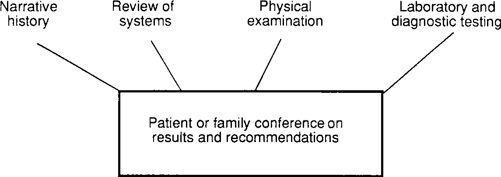

priate laboratory tests. Figure 10.1 summarizes the rheumatology consultation.

THE CHIEF COMPLAINT AND CONSTITUTIONAL

SYMPTOMS IN LUPUS

The most common initial complaint in early lupus is joint pain or swelling (in

50 percent of patients), followed by skin rashes (20 percent) and malaise or

fatigue (10 percent). Certain constitutional symptoms and signs are not included in the following chapters since they do not fall into any specific organ system;

Fig. 10.1.

The Rheumatology Consultation

History, Symptoms, and Signs

[63]

they are therefore reviewed here. These generalized body complaints consist of

fevers, weight loss, and fatigue.

Fever

Any inflammatory process is commonly associated with an elevated temperature.

The official definition of a fever is 99.6ЊF or greater (most of us have 98.6ЊF

as a normal temperature). Nevertheless, many patients have normal temperatures

that are in the range of 96Њ to 97Њ, and what is normal for some individuals may be a fever for others. Lupus surveys published in the 1950s documented low-grade fevers in 90 percent of patients. This number has decreased to 40 percent in recent reviews—a consequence of the widespread availability and use of

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially those over-the-

counter medications that can reduce fevers. These include aspirin, naproxen, and ibuprofen (e.g., Advil, Aleve); acetaminophen (e.g., Tylenol) can also decrease fever. Many lupus patients chronically run temperatures one to two degrees

above normal without any symptoms.

The presence of a temperature above

99.6

Њ

F without obvious cause suggests an infectious or inflammatory process

.

At times, I may find a normal temperature reading in a patient with a history

of fevers and wonder whether or not a fever is really present. It may be helpful for certain patients to keep a fever logbook or to record temperature readings

three times a day at the same hours for a week or two and to show it to their

physician. Fever curve patterns may suggest different disease processes.

A low-grade fever is not usually dangerous, other than its ability to cause the pulse to rise, which decreases stamina. In certain circumstances, fevers act as warning signs of infection and suggest the need for cultures, specific testing, or antibiotics. If the temperature rises above 104ЊF, precautions should be taken to prevent seizures or dehydration. This might include alternating between aspirin and ibuprofen or acetaminophen every 2 hours, sponging down the head and

body to lower the fever, taking plenty of fluids, or admitting the patient to the hospital.

The presence of a significant fever in any patient taking steroids (e.g.,

prednisone) or chemotherapy drugs should be taken very seriously

and is often a reason for hospitalization. Steroids usually suppress fevers and can mask infections.

Anorexia, Weight Loss, and Weight Gain

Half of all patients with lupus have a loss of appetite (anorexia), with resulting weight loss. The loss of more than 10 percent of body weight over a 3-month

period is rare and indicates a serious condition. Usually noted in the early stages of lupus, anorexia and weight loss are associated with disease activity. Evidence

[64]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

of active lupus often results in the administration of corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), with subsequent weight gain. If your doctor has detected large amounts of protein in your urine, you have what is termed ‘‘nephrotic syndrome.’’ Seen

in up to 15 percent of those with lupus, this also results in weight gain.

Malaise and Fatigue

Malaise is the sense of not feeling right. It conveys a message of aching, loss of stamina, and the ‘‘blahs.’’ Loss of stamina or decreased endurance associated with a tendency to be tired is known as fatigue. Malaise and fatigue are observed in 80 percent of SLE patients at some point during the course of their disease; in half of these, it can be disabling. Evidence of active disease or inflammation as well as infection, depression, anemia, hormonal problems, and stress may

also be associated with malaise and fatigue. The management of malaise and

fatigue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 25.

Summing Up

Before physicians can treat lupus, they must take a detailed history, perform a physical examination, and order proper laboratory tests. An accurate diagnosis

encompassing all symptoms and physical signs is the goal of a consultation.

The patient may have more than one process going on at the same time, and

these frequently benefit from different approaches. Both patient and doctor

should be flexible in how they understand the concept of disease and allow

themselves to consider differing viewpoints as to what might be responsible for a specific medical complaint. Many things may contribute to fatigue, for example. And as we’ve seen all along, lupus is a complex disease that can be